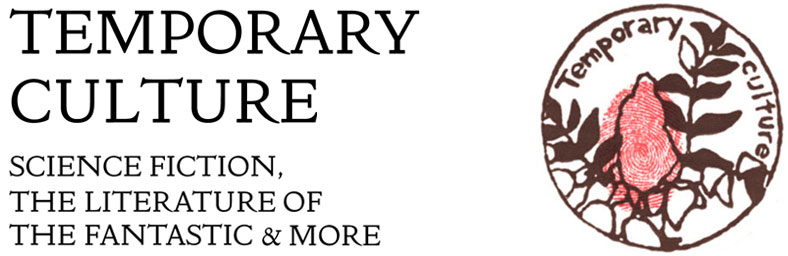

Richard Jefferies. After London; or, Wild England. [. . .] In Two Parts: Part 1 – The Relapse into Barbarism. Part II – Wild England. London: Cassell and Company, 1885.

Presentation inscription on half title: “John & Alice Brook from the Author, May 10th 1885.”

No. 9.

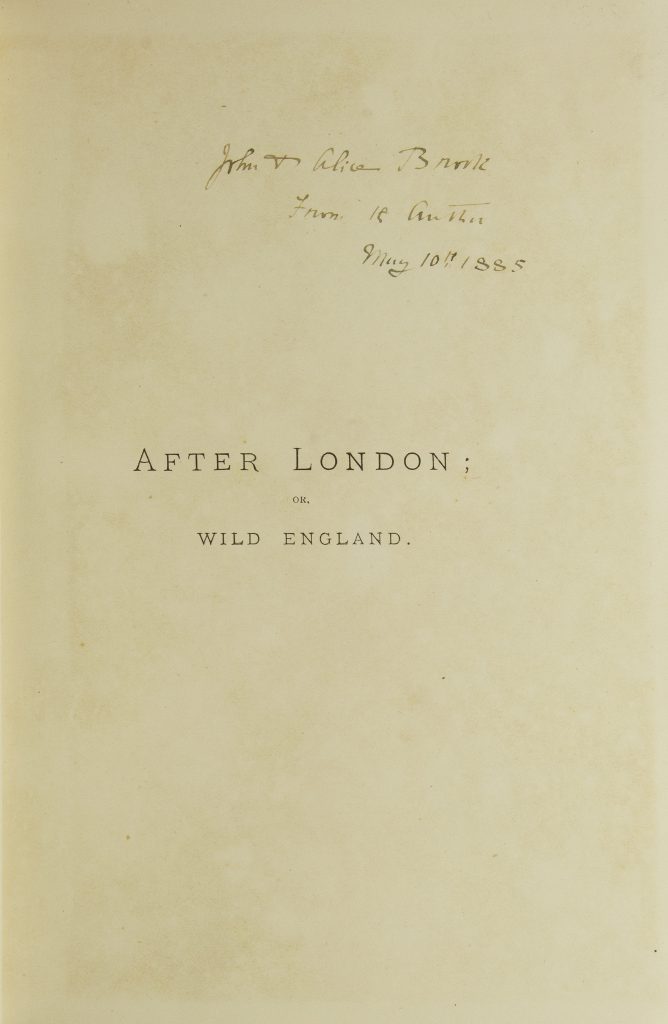

(CUALA PRESS) Lord Dunsany. Selections from the Writings of Lord Dunsany. Churchtown: Cuala Press, 1912.

Early writings by Lord Dunsany (1878-1957), with an introduction by William Butler Yeats, “printed by village girls at Dundrum,” to remind us that there is no separation between the literary and the fantastical.

Lily Yeats’ copy with her bookplate and ownership note on the title page, “Lily Yeats her book.”

No. 14.

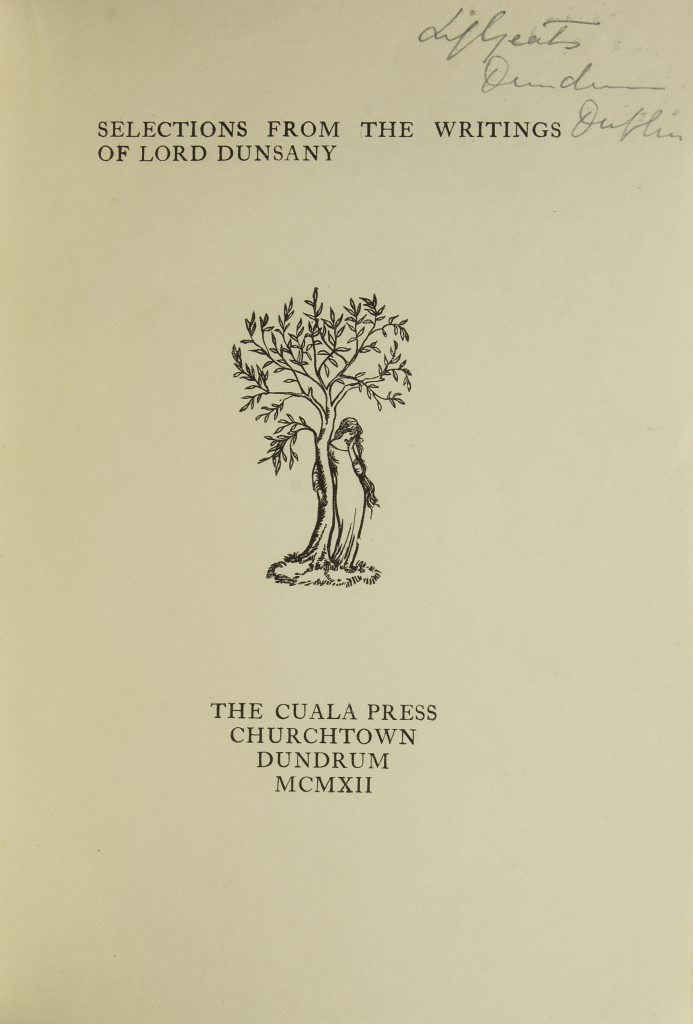

Stella Benson. Living Alone. London: Macmillan, 1920.

Second printing (originally published 1919).

With the ownership signature of Peggy Guggenheim, 1920, on flyleaf.

No. 16.

Lord Dunsany. The King of Elfland’s Daughter. London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924. Large paper copy, one of 250, signed by the author at the Preface.

Dunsany’s masterpiece, a tale of yearning and loss. The prose calls to be read aloud, the images are sharp, and there are some very funny passages. Alveric comes to Elfland and woos the King’s daughter, Lirazel, who flees with Alveric to “the fields we know,” her diadem of ice melting as she crosses the border. Lirazel bears a son, but she can never really get the hang of ordinary human life. One day blows away with the autumn leaves, back to Elfland. Once there, she pines for the human life she knew.

No. 17.

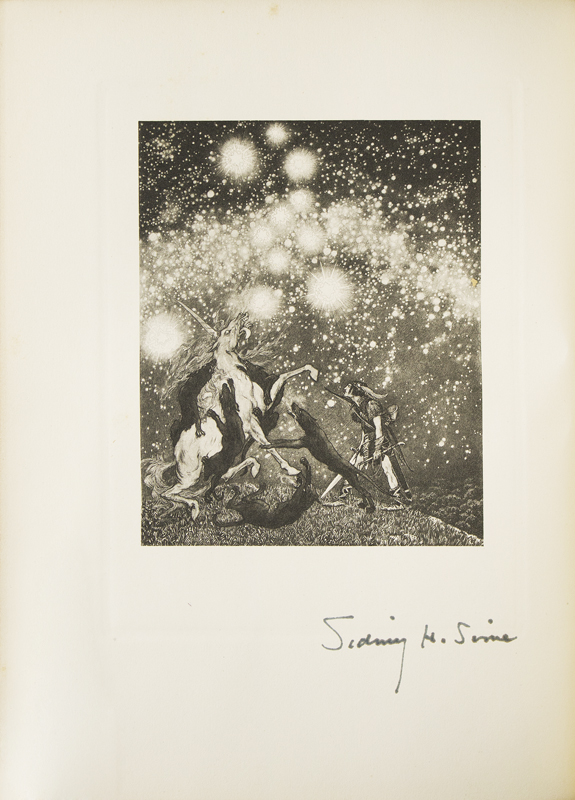

Lord Dunsany. The King of Elfland’s Daughter. London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924. Large paper copy, one of 250 copies.

The photogravure frontispiece, signed by artist Sidney H. Sime.

No. 17.

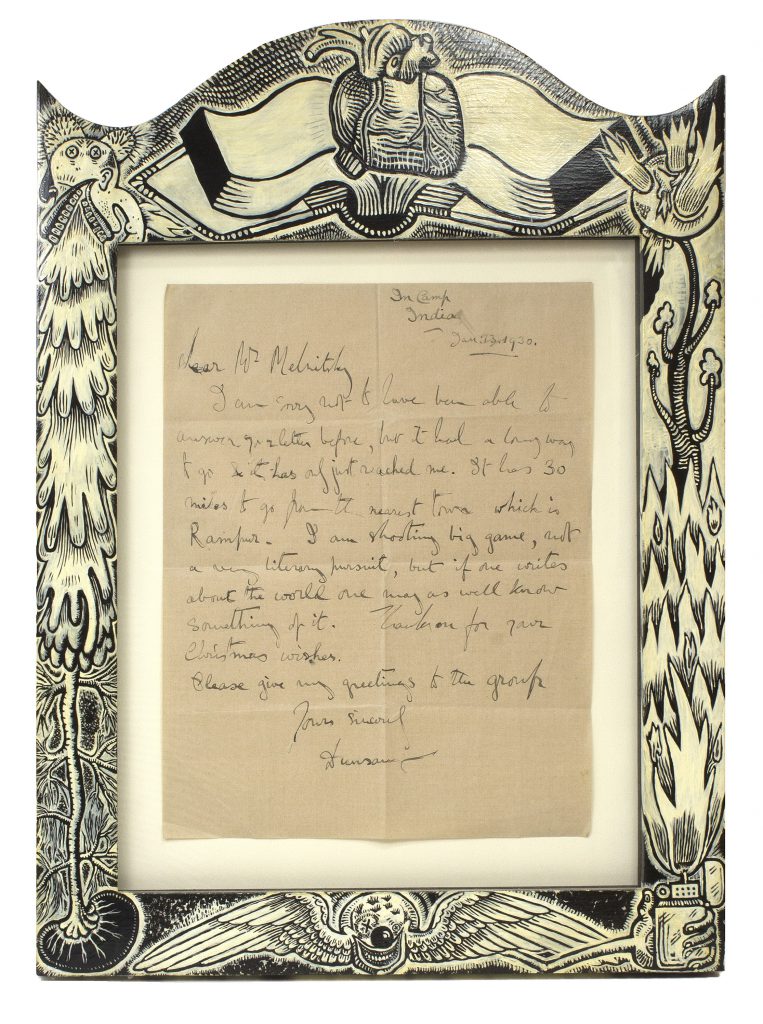

Lord Dunsany. Autograph letter, signed, In Camp, India, Jan. 13, 1930. In a hand-painted vernacular American Gothic frame, signed by cowpunk musician Stephen Fredette, 1994.

“I am shooting big game, not a very literary pursuit, but if one writes about the world, one may as well see something of it.”

This letter, written somewhere in India, evokes for me Dunsany’s tall tales of Joseph Jorkens at the Billiards Club, which often involve travel in remote areas.

H. P. Lovecraft’s praise of Dunsany’s work and Lin Carter’s paperback editions of Dunsany in the 1970s ensured that subsequent generations of American readers of fantasy and horror revered him.

No. 17.

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman. London: Chatto & Windus, 1926.

With an autograph quotation, signed: “Sylvia Townsend Warner ‘Laura hated ink’ p. 210”.

No. 19.

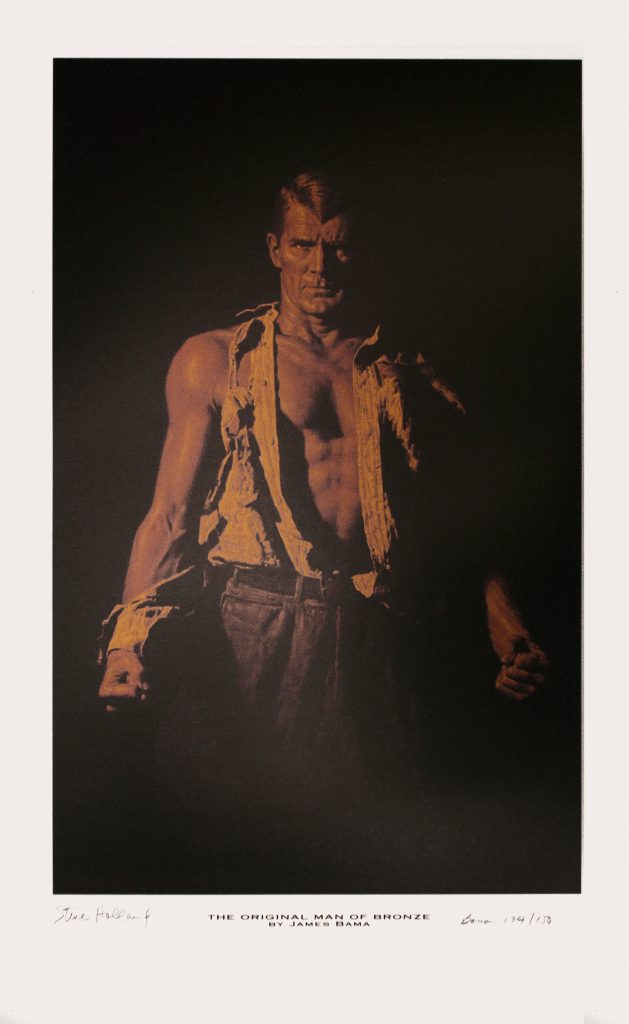

James Bama. The Original Man of Bronze. Anaheim: Graphitti Designs, 1994.

Print of the original painting for the Bantam cover of The Man of Bronze. Edition of 150, signed by the artist and by model Steve Holland.

Prolific and versatile artist James Bama painted more than 60 illustrations for the Bantam covers, and Steve Holland was the model for these and for countless mass-market paperback book covers by Bama and others. Holland was “the embodiment of the spirit of Men’s Adventure circa 1973” (Chris Brown).

No. 24.

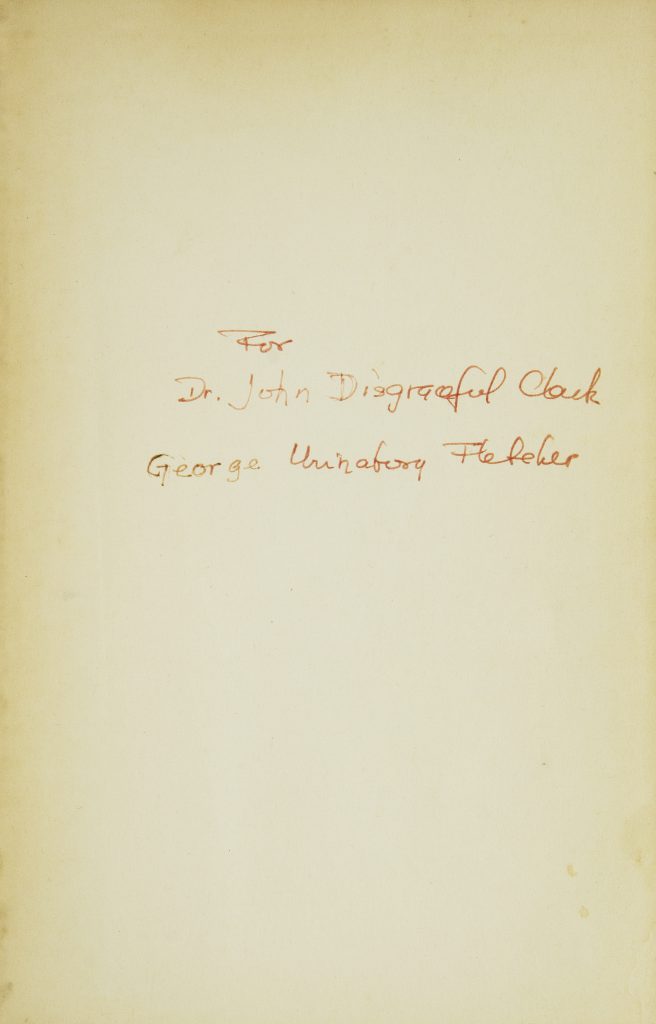

Fletcher Pratt. The Well of the Unicorn. By George U. Fletcher. New York: William Sloane Associates, 1948.

Fletcher Pratt’s The Well of the Unicorn (1948) is a well written and unduly neglected novel of revolution in a late mediaeval fantasy setting. Pratt charts personal and sexual intrigue alongside guerrilla actions, political discussions, and reflects upon the consequences of using magic to achieve revolutionary aims.

Inscribed by Pratt to his friend John D. Clark on the front flyleaf, “To John Disgraceful Clark, George Urinaborg Fletcher.”

No. 27.

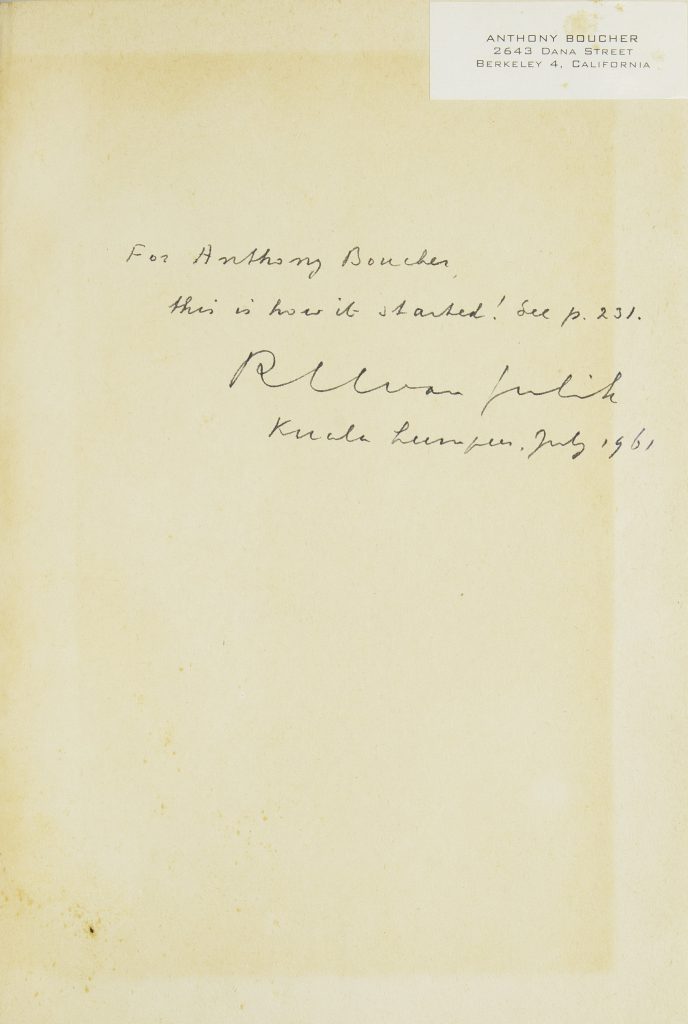

Robert Hans van Gulik. Dee Goong An. Three Murder Cases Solved by Judge Dee. An old Chinese detective novel translated from the original Chinese with an introduction and notes. Tokyo: Printed for the author by Toppan Printing Company, 1949.

R. H. van Gulik (1910–67), Dutch diplomat and sinologist, also wrote a series of detective novels set in China of the Tang dynasty (eighth century CE). His scholarly knowledge enriched plots adapted from earlier Chinese sources, including incidents of possible supernatural origin. I include van Gulik’s Judge Dee novels among the literature of the fantastic because of his rigorous creation of an ancient China, and for his connection with Tony Boucher.

This copy was inscribed to author and critic Anthony Boucher by van Gulik when he was posted to Kuala Lumpur.

No. 32.

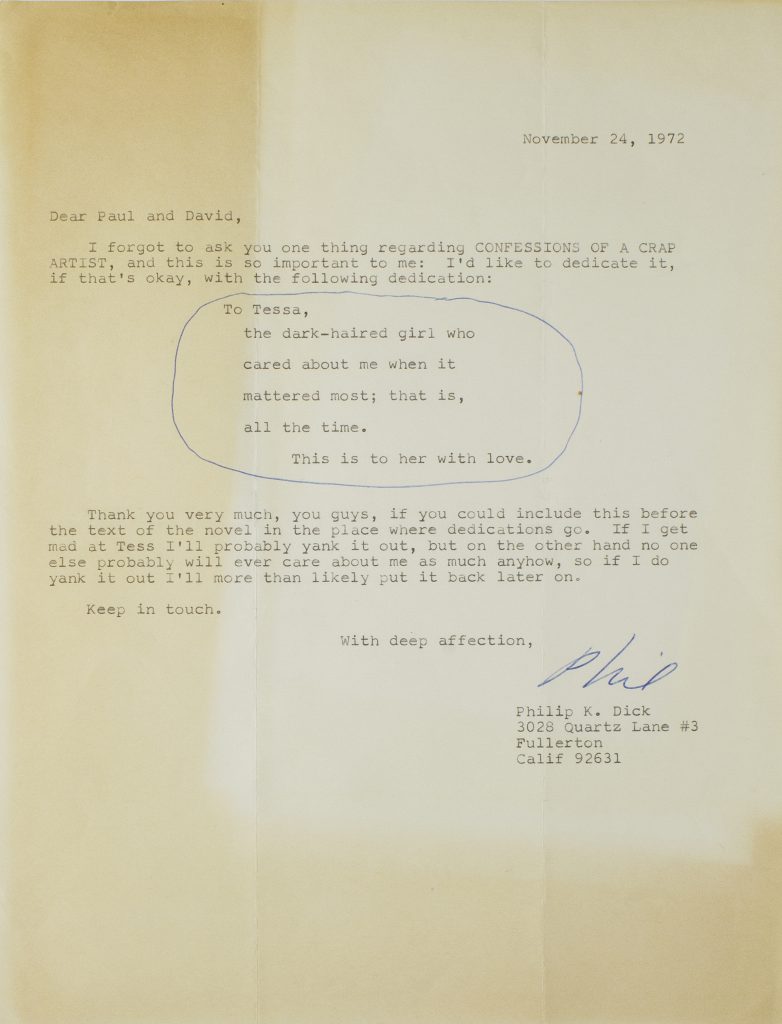

Philip K. Dick. Typed letter, signed (“Phil”) to David G. Hartwell and Paul Williams, 24 November 1972.

This letter is the dedication page for Dick’s novel Confessions of a Crap Artist, which he wrote at about the same period as Time out of Joint, but which was not published until 1975. Biographer Lawrence Sutin called it “Phil’s first novel to put multiple narrative viewpoints to wild work.”

Dick was known chiefly in the science fiction community until 1975, when Paul Williams’ interview and profile in Rolling Stone made him a national figure. He died of a stroke in 1982, aged fifty-three, just after the release of Bladerunner, based on his 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? It was the first of many film adaptations of his work. Critic Fredric Jameson has called him “the Shakespeare of science fiction.”

No. 34.

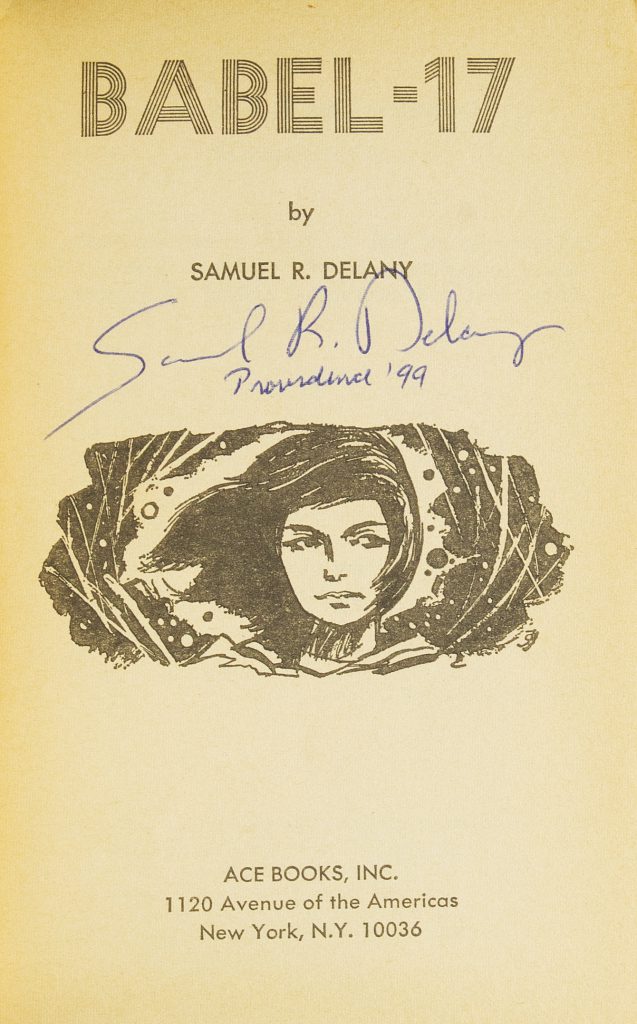

Samuel R. Delany. Babel-17. New York: Ace Books, [1966].

Signed by the author.

No. 36.

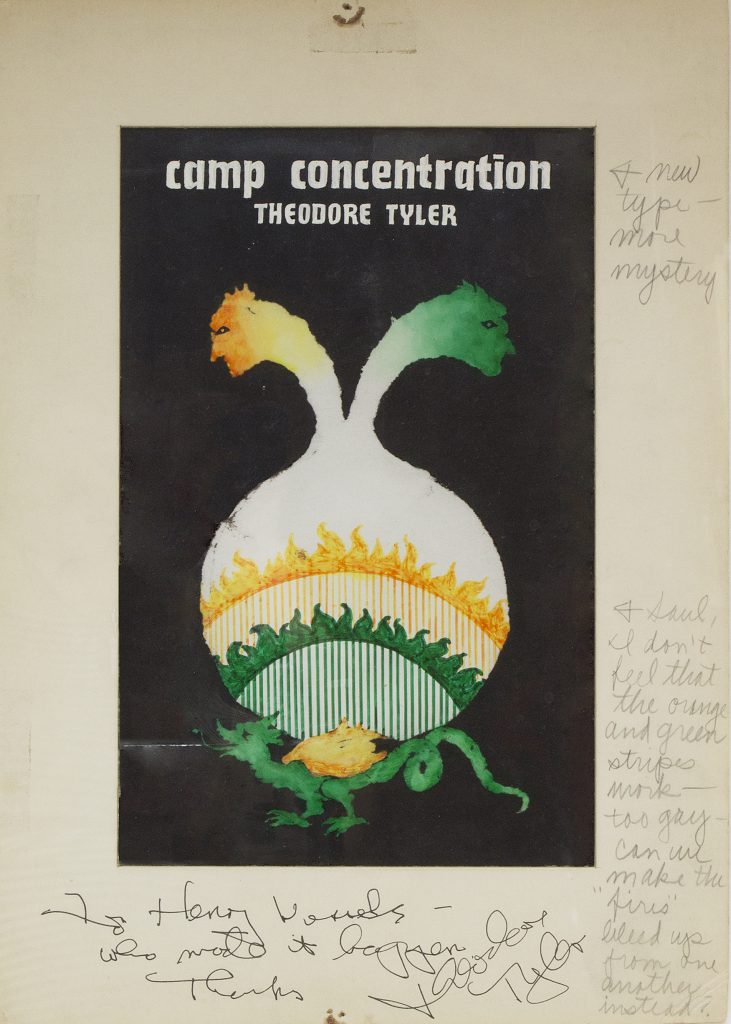

(Thomas M. Disch) Saul Lambert. Camp Concentration Theodore Tyler. Mock-up of cover art, marked for revisions. [New York, 1969].

Dust jacket art for the American edition of Camp Concentration, later inscribed by Disch, also signed by him in jest as “Theodore Tyler.”

No. 39.

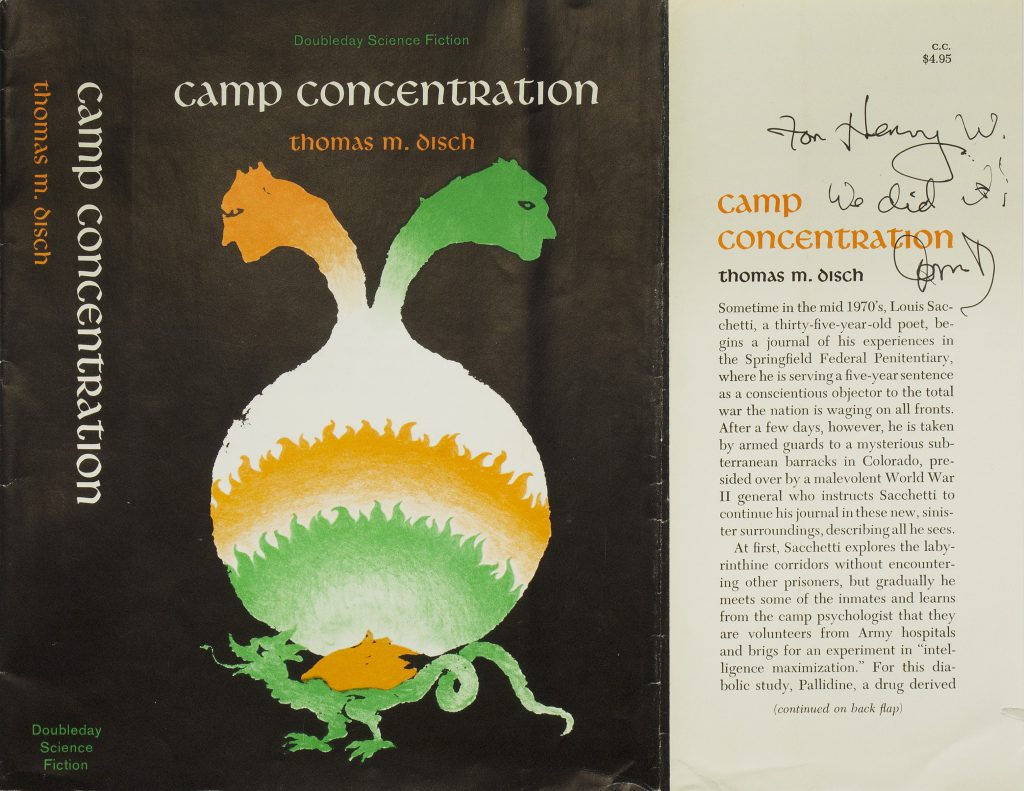

Thomas M. Disch. Camp Concentration. Garden City: Doubleday, 1969.

Proof copy of the Doubleday dust jacket, signed by Disch.

No. 39.

James Blish. Doctor Mirabilis. A Novel. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1971.

“These were words of power.”

Doctor Mirabilis is a science fiction novel of the history of science, a fictional study of Roger Bacon, the thirteenth-century English monk, scientist, and philosopher. James Blish (1921-1975), author and critic, was interested in Bacon as the originator of the scientific way of thinking, which Blish called “the theory of theories as tools.” Blish’s visionary approach and the discovery that Bacon makes at the heart of the book (deciphering the dream-encoded formula for black powder) embody the notion of conceptual breakthrough central to science fiction.

Signed by the author on the title page.

No. 40.

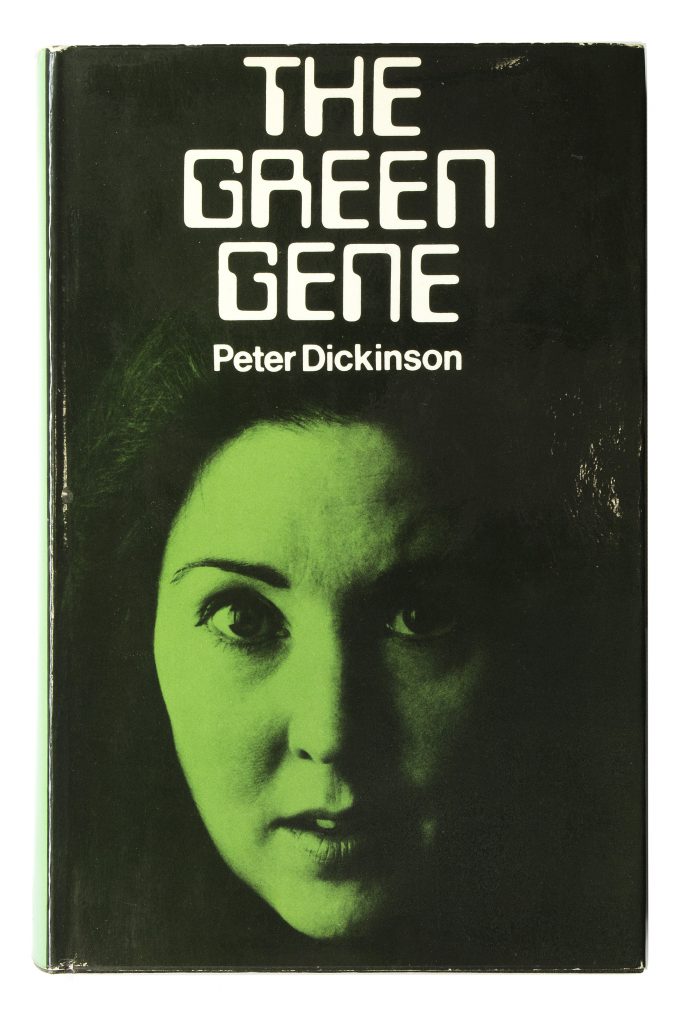

Peter Dickinson. The Green Gene. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1973.

The Green Gene is a comic satire of Anglo-Celtic relations that masks some brutal truths about English racism. It is indisputably science fiction because of the key roles that genetics, statistics, and computers play in the novel. A genetic accident, the Green Gene, has given all Celts green skin. At a time when there was no language available outside a subset of mathematics to describe computer programming, and in a Britain with only two sophisticated computers (one at the Race Relations Board, the other at Treasury), The Green Gene is the earliest novel of computer hacking: terrorists introduce a “computer rat” to disrupt the function of the central computer and ultimately discredit the racist policies of the establishment.

No. 41.

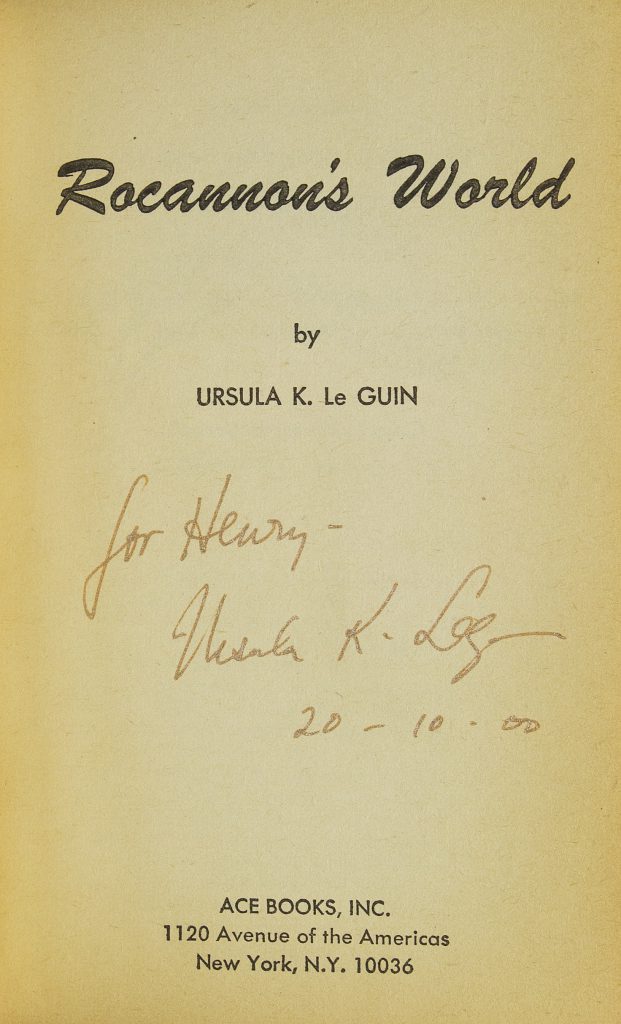

Ursula K. Le Guin. Rocannon’s World. New York: Ace Books, 1966. Ace Double G-574. Bound with: Avram Davidson. The Kar-Chee Reign.

Inscribed by the author on the title page.

No. 42.

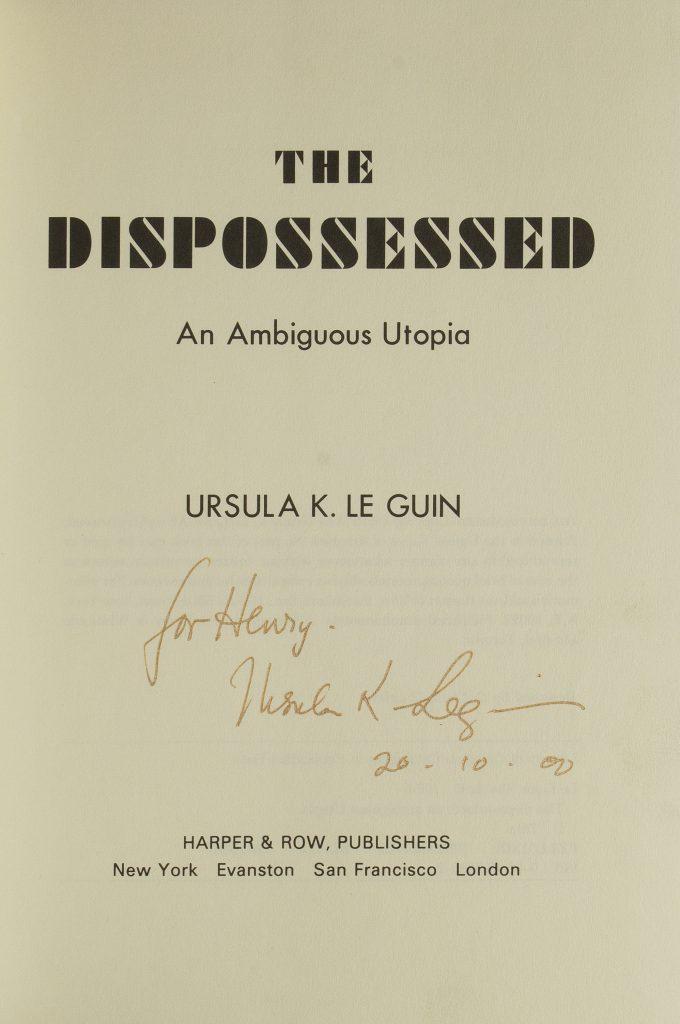

Ursula K. Le Guin. The Dispossessed. An Ambiguous Utopia. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Le Guin’s novel of a moon and its planet: the stark, almost desert-like world of the moon Annares, an anarchist cooperative society, and the much larger capitalist world of Urras. The book starts simply. “There was a wall. It did not look important.” Shevek, mathematician of Annares, arrives in Urras with nothing but his ideas, which are revolutionary. The Dispossessed won the Hugo and Nebula awards.

No. 42.

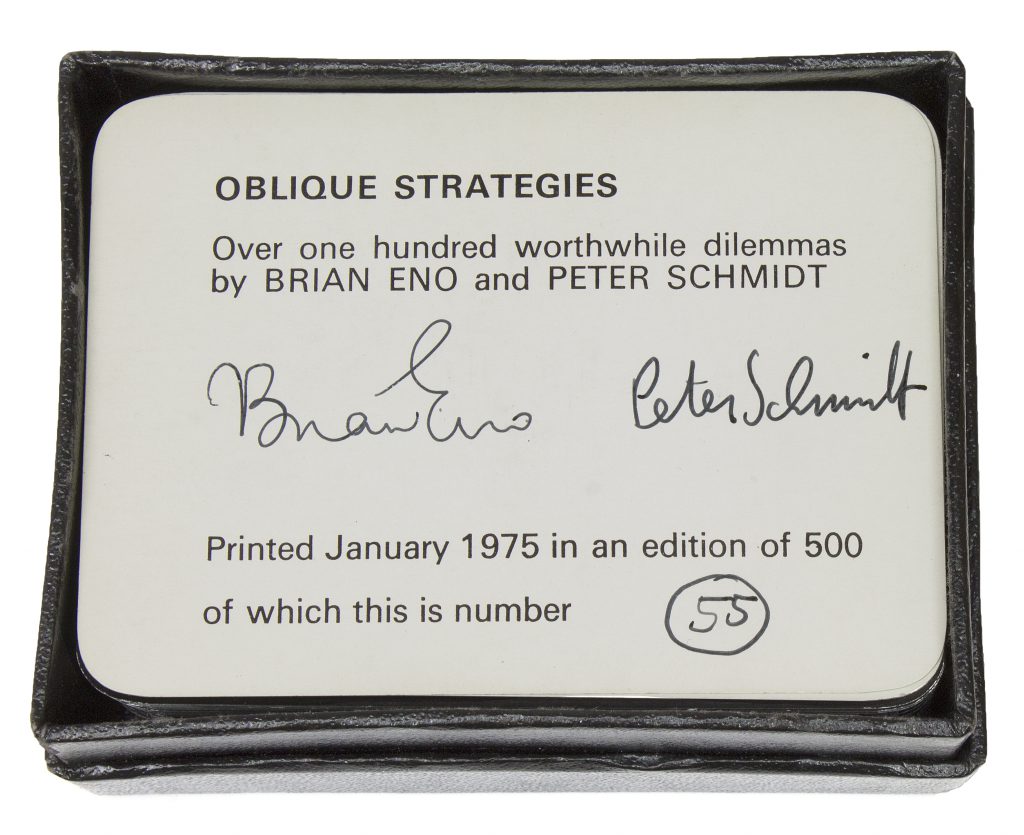

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt. Oblique Strategies. Over one hundred worthwhile dilemmas. London: January 1975.

A deck of instruction cards intended to introduce elements of chance into any creative process. Eno used these during the recording of Another Green World, which often challenged the musicians working with him on Another Green World, but Eno ended up with a masterpiece where synthesizers, electric guitar, and vocals evoke strange landscapes and richly textured narratives.

The first edition, one of 550 copies, signed by Eno and Schmidt. In the original black paper box.

No. 43.

Alice Sheldon. Ten Thousand Light-Years from Home. By James Tiptree, Jr. With a new Introduction by Gardner Dozois. Boston: Gregg Press, 1976.

Alice Sheldon (1915–87) wrote most of her fiction in the span of a single tumultuous decade in America, 1967–77, under the pseudonym of James Tiptree, Jr. The Tiptree voice expressed an easy competence and clarity and an understanding of the way worlds worked. Tiptree stories are almost invariably about death: beautifully written, sometimes very funny and sometimes very sexy, but inexorable and unflinching.

In 1977, a fan writer revealed Tiptree’s identity. Alice Sheldon wrote to a correspondent, “As to writing, I am dead.”

Inscribed by the author to her editor, “Dave Hartwell with unbounded regard James Tiptree Jr. Alli.”

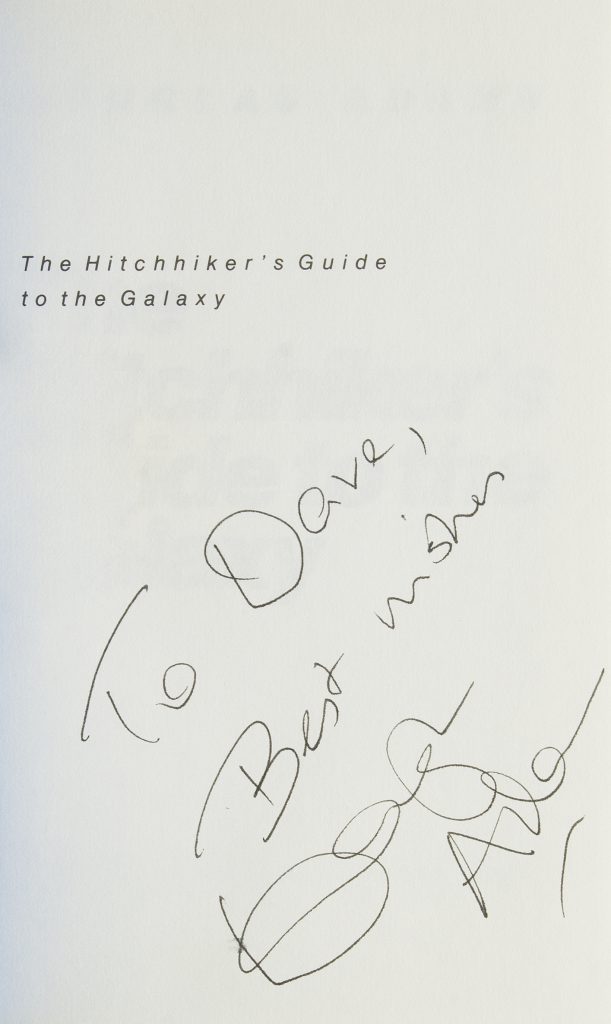

No. 44.Douglas Adams. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Harmony Books, 1980.

The comic misadventures of gormless Earthling Arthur Dent, as he travels the galaxy with Ford Prefect, a guy “who really knows where his towel is.” Based on on the BBC radio show, this novel mocks the militaristic tendencies and standard characters of pulp science fiction, all of which persist in film.

In many ways, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is the complete opposite of Star Wars — call it Star Peace — and in that respect it is in the line of the British New Wave: a British answer to American dominance. Douglas Adams freely acknowledged the influence of the work of Robert Sheckley.

First American edition, inscribed by the author to David G. Hartwell on the half-title page.

No. 47.

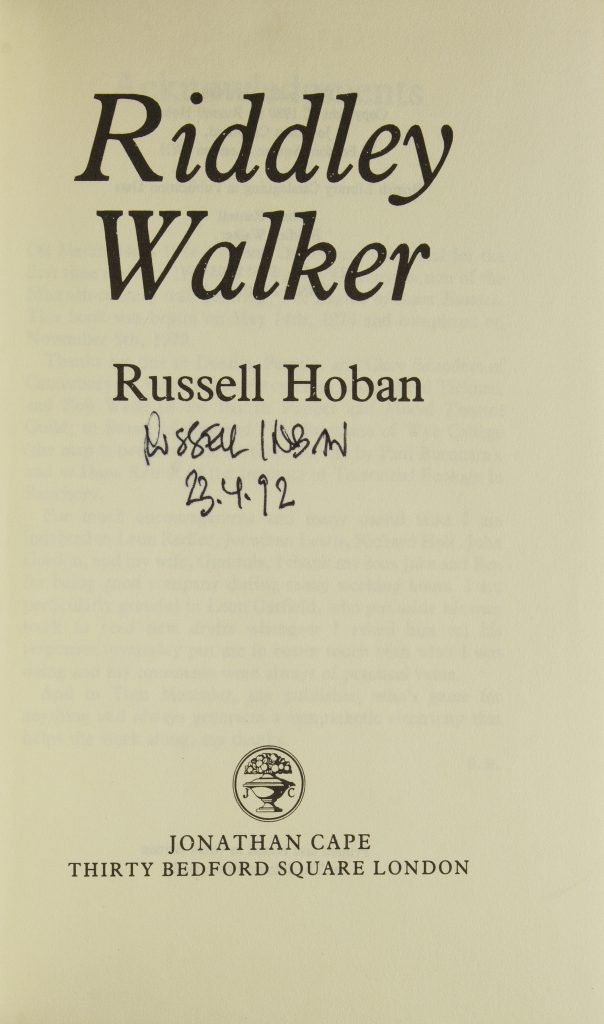

Russell Hoban. Riddley Walker. London: Jonathan Cape, 1980.

Language is the beating heart of Riddley Walker, a novel set in the ruined landscape of Kent long after the end of our civilization. The English that young Riddley Walker speaks is debased and savage but still vital and immediately comprehensible. It encodes secrets vaster than the young man can know: the old oral lore contains the long-lost formula for gunpowder. Echoes of Doctor Mirabilis here, at the other end of time.

No. 48.

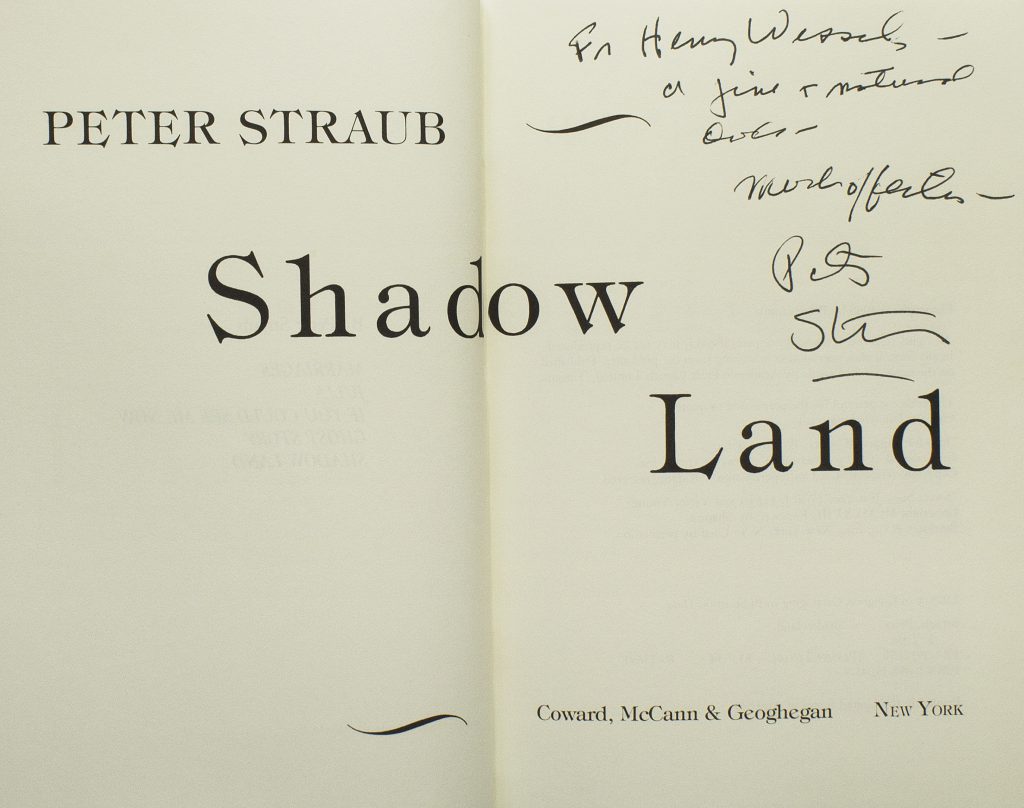

Peter Straub. Shadow Land. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1980.

“To do magic, to do great magic, he has to know himself as a piece of the universe.”

“A piece of the universe?”

“A little piece that has all the rest of it. Everything outside him is also inside him.”

Peter Straub is one of the few magicians I have ever met: that rare real thing, a writer who starts a tale in a recognizable place and enables the reader to go somewhere unexpected and unsettling. Perception is malleable, suggests Straub; memory struggles against silence.

One summer long ago, schoolboys Tom and Del travel to Vermont to spend a summer with Del’s reclusive uncle, Coleman Collins, once a legendary magician and performer in England and on the Continent.

No. 49.

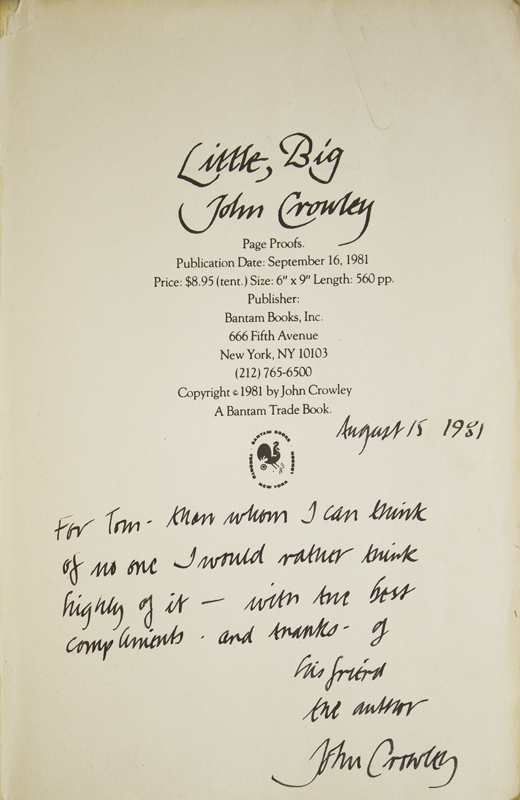

John Crowley. Little, Big. New York: Bantam, 1981.

John Crowley’s masterpiece is many novels, all of them a single tale, made of family and story and time. Little, Big is a multi-generational novel of an American family told in three intricately braided love stories. It is a tale of the porous boundaries between our world and the elsewhere of the fairy folk. The book is a dark dystopian account of the rise of an American demagogue as the nation’s infrastructure and institutions crumble. It also plays a nimble and sophisticated game with four hundred years of literature, from Shakespeare and Mother Goose to Alice in Wonderland and Thornton W. Burgess.

Little, Big is my favorite work of fiction, a book I have read and reread many times.

Proof copy, inscribed by the author to Thomas M. Disch.

No. 50.

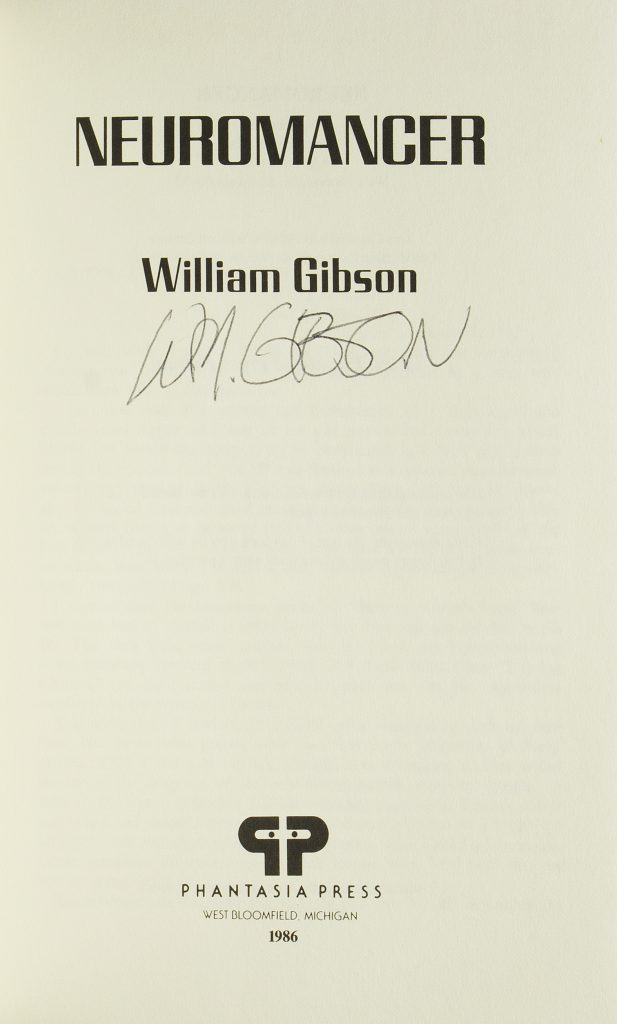

William Gibson. Neuromancer. West Bloomfield, Michigan: Phantasia Press, 1986.

Neuromancer was published as a paperback original in 1984. The world of the novel is a near-future urban sprawl, and the protagonists are computer-savvy lowlifes linking themselves into the matrix of data. The power structures the outlaw Case encounters are wealthy, untouchable, and not merely cosmopolitan, but post-national and post-human artificial intelligences residing on satellite colonies in orbit around the Earth. The prose is as clear and compelling as Raymond Chandler’s, and Neuromancer took the world of science fiction by storm.

First American hardcover edition, signed by the author.

No. 51.

Avram Davidson. And Don’t Forget the One Red Rose. Seattle: Dryad Press, 1986.

One of 15 hardcover copies signed by the author.

No. 52.

Avram Davidson. Adventures in Unhistory. Conjectures on the Factual Foundations of Several Ancient Legends [etc.]. Philadelphia [i.e., King of Prussia, Penna.]: Owlswick, 1993.

Publisher George Scithers’ copy, no. 1 of 72 numbered copies signed by the author and artist George Barr.

No. 52.

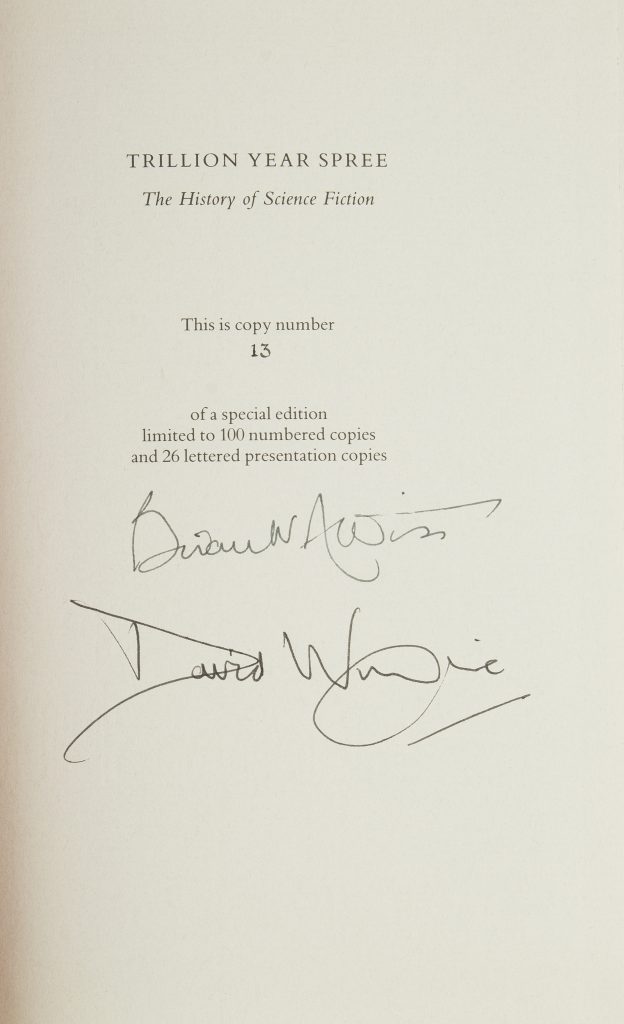

Brian W. Aldiss, with David Wingrove. Trillion Year Spree. The History of Science Fiction. London: Gollancz, 1986.

In 1973, Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) published Billion Year Spree, a history of the field notable for its advocacy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the key text in science fiction. This expanded edition is a colorful and often funny book, with portraits of writers, written by an “impartial insider,” who had been at the heart of British science fiction since the mid-1950s.

One of 100 numbered copies, signed by the authors, with an introduction by Aldiss not published in the trade edition.

No. 53.

Karen Joy Fowler. Sarah Canary. New York: Henry Holt, 1991

Sarah Canary is a first contact tale set in late nineteenth-century America. A strange, badly dressed white woman, with “skin poreless and polished,” shining like porcelain, appears near an itinerant railway workers’ camp in the woods of Washington. No one, not even a polyglot Chinese man, can understand her speech. She is confined to an asylum. “As an emblem of the enigma behind the idea of first contact she is perhaps definitive. As a dramatization of the self-deluding imperialisms of knowledge, Sarah Canary is equally convincing” (SFE). Fowler is also author of The Jane Austen Book Club (2004).

No. 55.

Bradley Denton. Buddy Holly Is Alive and Well on Ganymede. New York: Morrow, 1991.

Rock ’n’ Roll and science fiction, American style.

Signed by the author.

Denton’s Buddy Holly won the John W. Campbell award for best novel.

No. 56.

Timothy d’Arch Smith. Alembic. A Novel. Normal, Ill.: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992.

Rock ’n’ Roll and science fiction, British style.

The science in London antiquarian bookseller Timothy d’Arch Smith’s Alembic is early modern alchemy in the service of a modern bureaucratic state, and the rock ’n’ roll is Celestial Praylin, a band on the scale of Led Zeppelin. The antics of Nicholas Sparks, depraved megastar frontman of Celestial Praylin, the crazed adoration of the fans, and the scary manipulations of the government office of experimental alchemy are reported through the eyes of Thomas Graves. Graves is an antiquarian bookman, and the sort of overly sensitive, self-centered post-adolescent person who is the ultimate novel protagonist — so long as he survives the events and grows up to tell the tale.

The author portrait is by Duncan Andrews. Signed by the author on the title page, inscribed on the first blank, “To the Man Ray of Lexington Avenue . . .”; also signed by Duncan Andrews on the flyleaf, and with his original color photograph of the author.

No. 57.

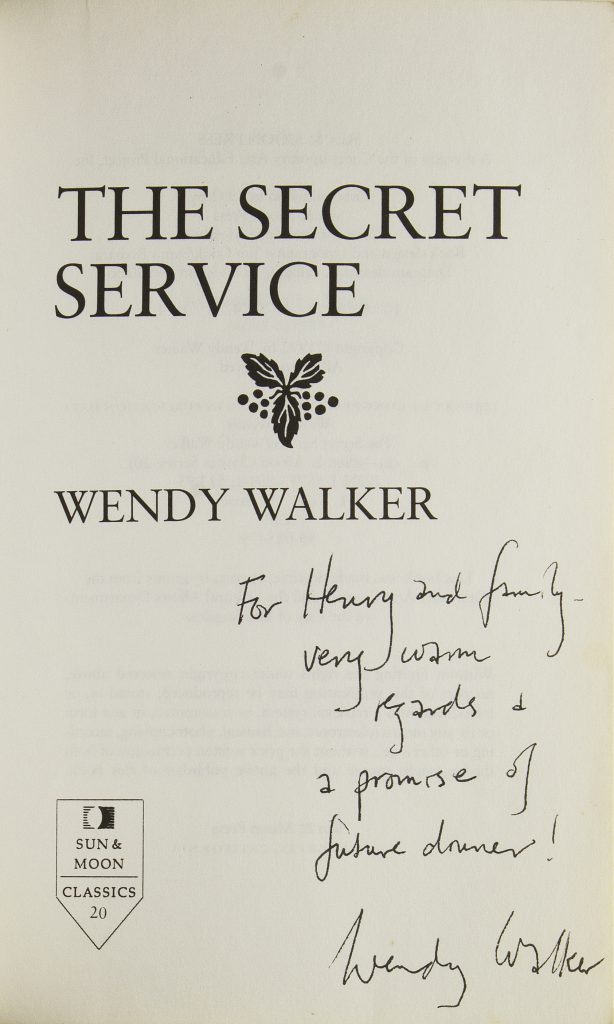

Wendy Walker. The Secret Service. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon, 1992.

The Secret Service tells the story of an elaborate nineteenth-century Catholic conspiracy against the English monarchy, complete with dastardly continental noblemen — aesthetes of prodigious sophistication and guile — and a mysterious heiress sequestered in a tower impregnable. Walker’s astonishing conceit is that the three principal British agents of the eponymous secret service have the capacity to transform themselves into objects, the better to spy upon the conspirators: a crystal wine goblet, a salmon rose swaying where there is no breeze; and a bronze statue. Mind and perception are dependent upon the form of their container and Walker gives us the altered sensibilities of the spies. This is the great underrated book of the 1990s.

No. 58.

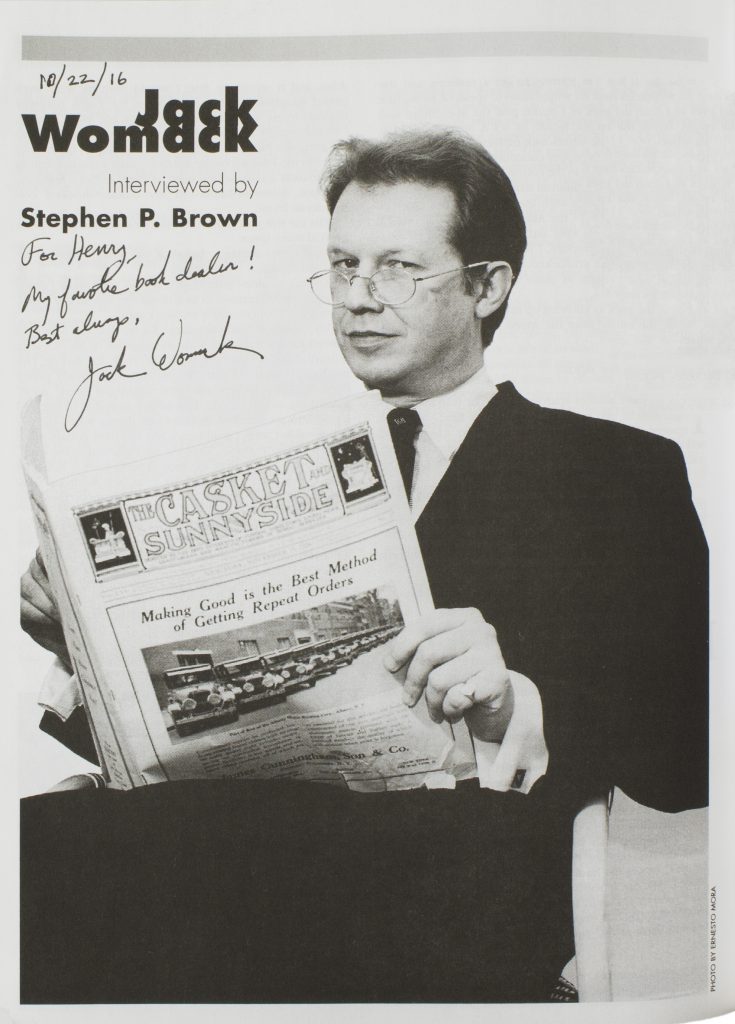

Jack Womack interviewed by Stephen P. Brown, [and:] William Gibson interviewed by Jack Womack, [in:] SF Eye Issue #15. Asheville, North Carolina: SF Eye, Fall 1997.

Inscribed by Jack Womack.

No. 59.

John Clute. The Darkening Garden. A Short Lexicon of Horror. Seattle: Payseur & Schmidt, 2006.

With: Postcards of Doom. A Journey from Affect to Vastation. Thirty artists, thirty motifs. Seattle: Payseur & Schmidt, 2006.

The Darkening Garden builds upon Clute’s distinctive critical vocabulary, and its definitions are so rich in allusion that it functions as an encyclopaedia in miniature. In its discussion of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Clute demonstrates his willingness to reassess earlier findings. This edition was illustrated by thirty artists, each illustrating a descriptive term. The Postcards of Doom reproduce the illustrations and were issued as a set in conjunction with The Darkening Garden.

No. 60.

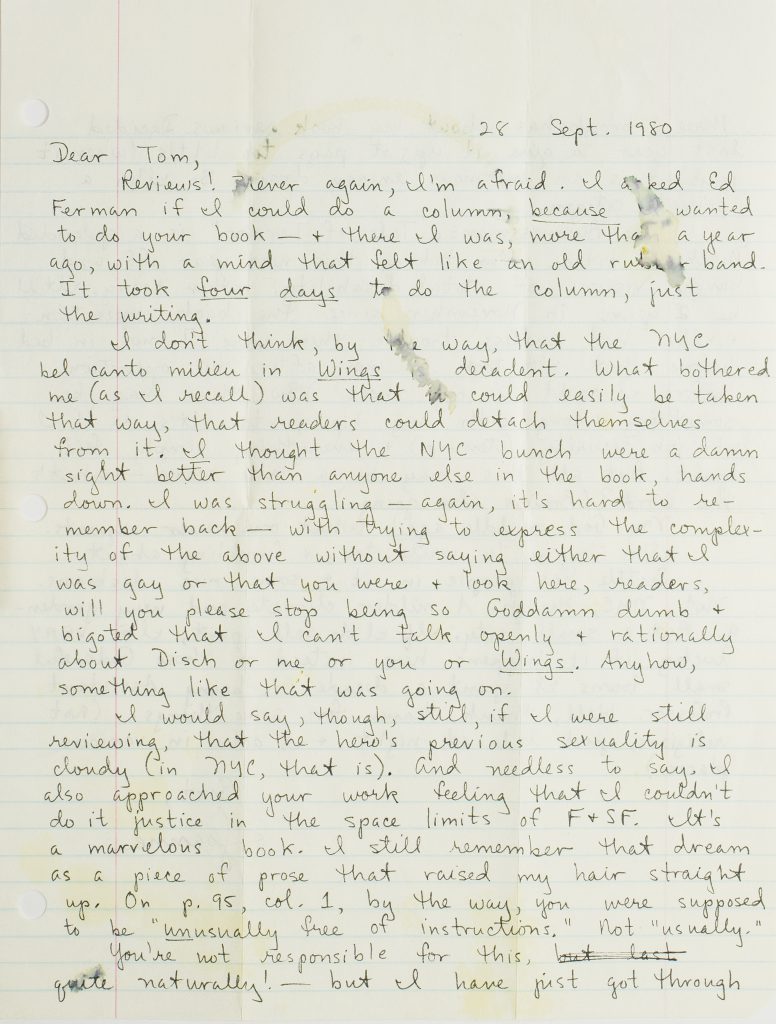

Joanna Russ. Autograph Letter, signed, to Thomas M. Disch, 28 September 1980.

Joanna Russ (1937–2011) is the rainy night sky when the whole box of fireworks goes up at once, a blazing angel saying, Look! She was one of the fiercest intellects in science fiction in the 1960s and 1970s, a writer of excellent short fiction and one of the best critics of contemporary work and earlier authors. Ill health largely curtailed her fiction and critical writing after the early 1980s.

She writes her friend Tom Disch, whose novel On Wings of Song (1979) she had just reviewed: “Reviews! Never again, I’m afraid.”

No. 61.

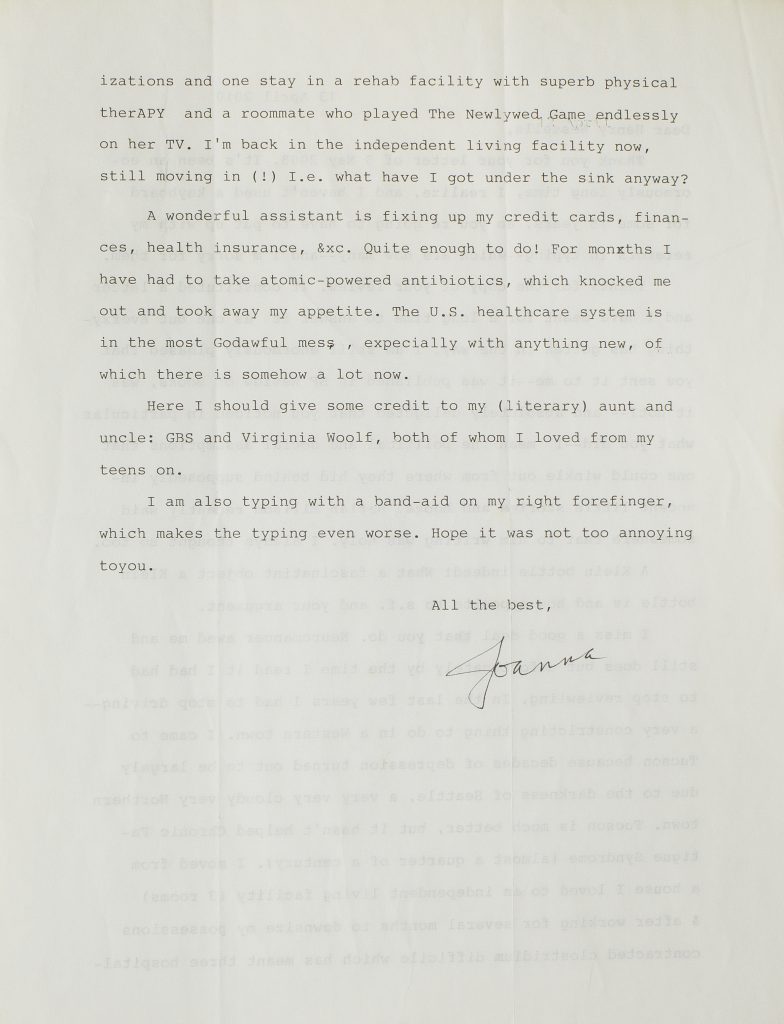

Joanna Russ. Typed Letter, signed, to Henry Wessells, 13 April 2010.

“What a fascinating object a Klein bottle is and how apposite to s.f. and your argument. [. . .] Neuromancer awed me and still does but unfortunately by the time I read it I had to stop reviewing.”

No. 61.

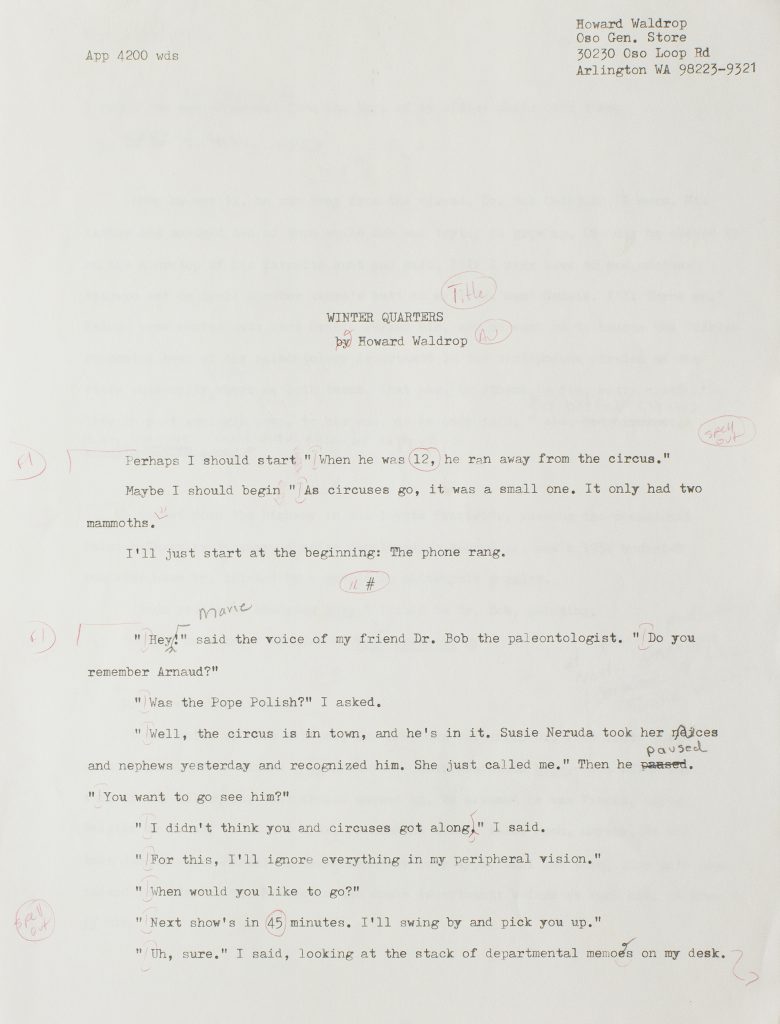

Howard Waldrop. Winter Quarters. Original typescript with revisions in the author’s hand, marked for typesetting in red by Ellen Datlow, summer 2000.

Howard Waldrop is an American original, a brilliant author whose recognition has largely been among other writers and a small group of editors. He makes things happen like no one else can. “Winter Quarters,” a story of the cloning of extinct species and a small-time circus, one that “only had two mammoths,” includes a remarkable and utterly chilling one-page Brechtian vaudeville of the Holocaust.

No. 62.

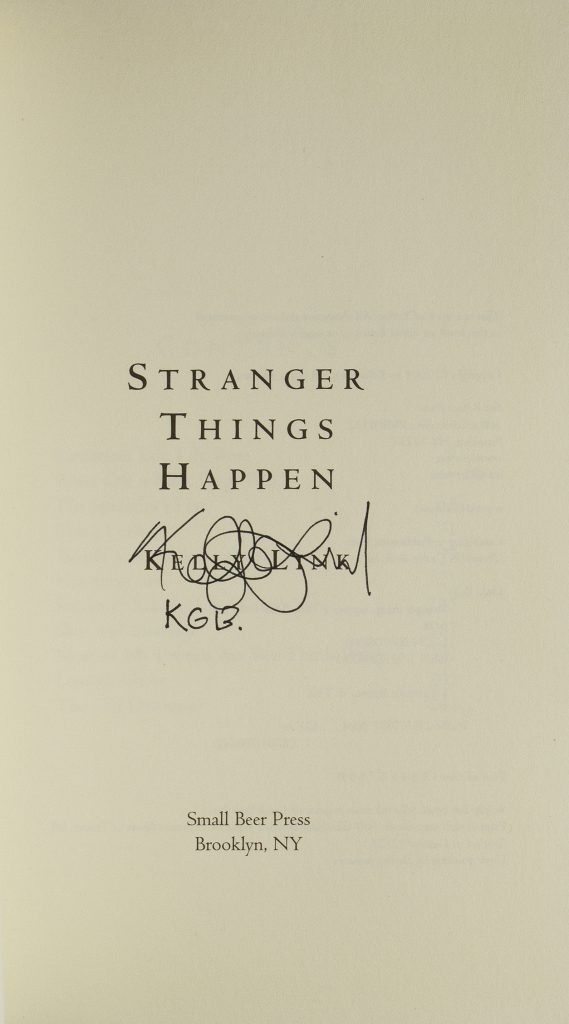

Kelly Link. Stranger Things Happen. Brooklyn, NY: Small Beer Press, 2001.

First book by the critically acclaimed Kelly Link, whose short fiction has won the Hugo, Nebula, Tiptree, and World Fantasy awards.

Also the first book from Small Beer Press, who have gone on to publish many notable award-winning books from established authors as well as by new writers.

No. 64.

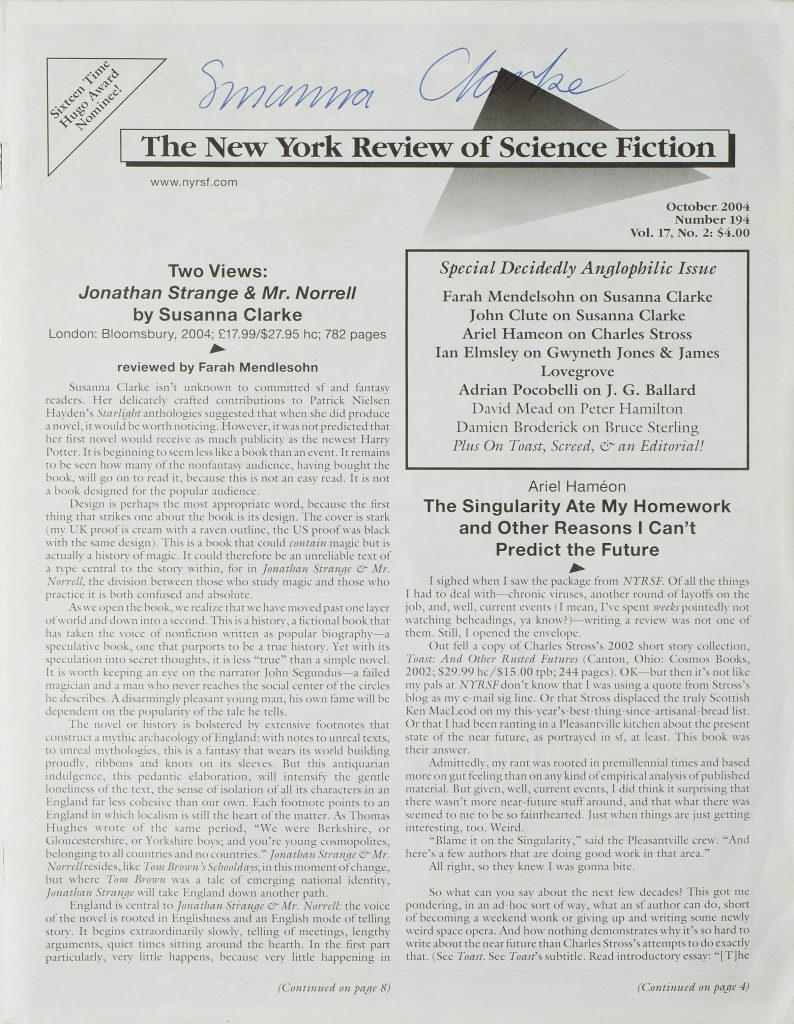

The New York Review of Science Fiction. Special Decidedly Anglophilic Issue. Vol. 17, No. 2. October, 2004.

Signed by Susanna Clarke across the top.

With reviews of Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Farah Mendlesohn and John Clute.

No. 66.

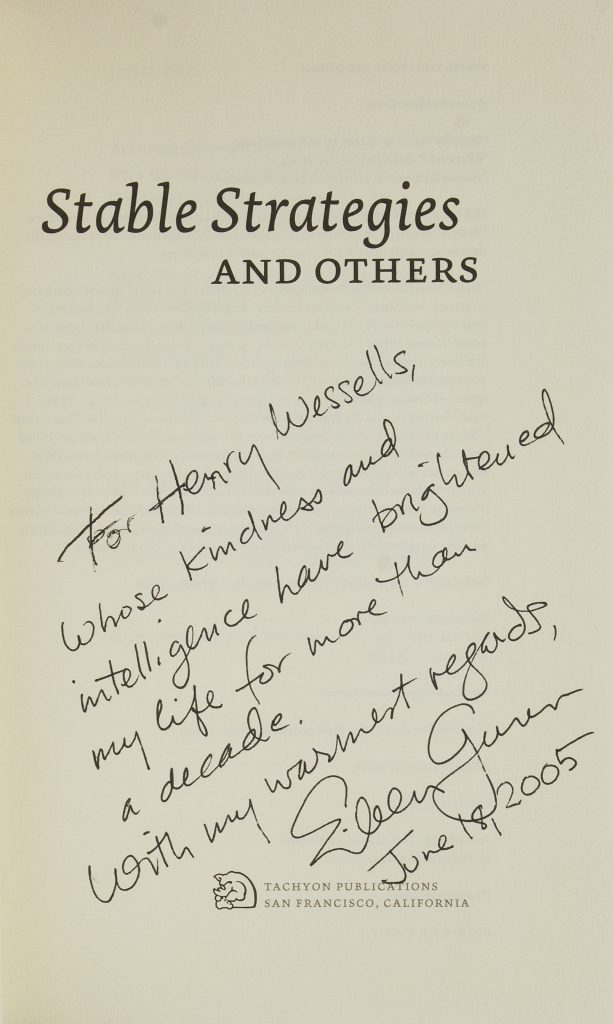

Eileen Gunn. Stable Strategies and Others. San Francisco: Tachyon, 2004.

“It doesn’t follow the old rules.”

Stable Strategies and Others, from San Francisco publisher Tachyon, is a collection assembling stories of corporate and social life in the age of the computer and mass media. Gunn was a director of the advertising department of Microsoft in the mid-1980s, and “Stable Strategies for Middle Management” (1988) is a satire of an office culture where bioengineering modifications are the stepping-stone to success. Other tales look at teen culture, childhood education, and Richard Nixon as a television talk show host. Gunn has a vast acquaintance in science fiction, and several of her stories have been collaborations with other writers in the field. Her website The Infinite Matrix (2001–8) was a brilliant literary science fiction magazine in online form.

No. 67

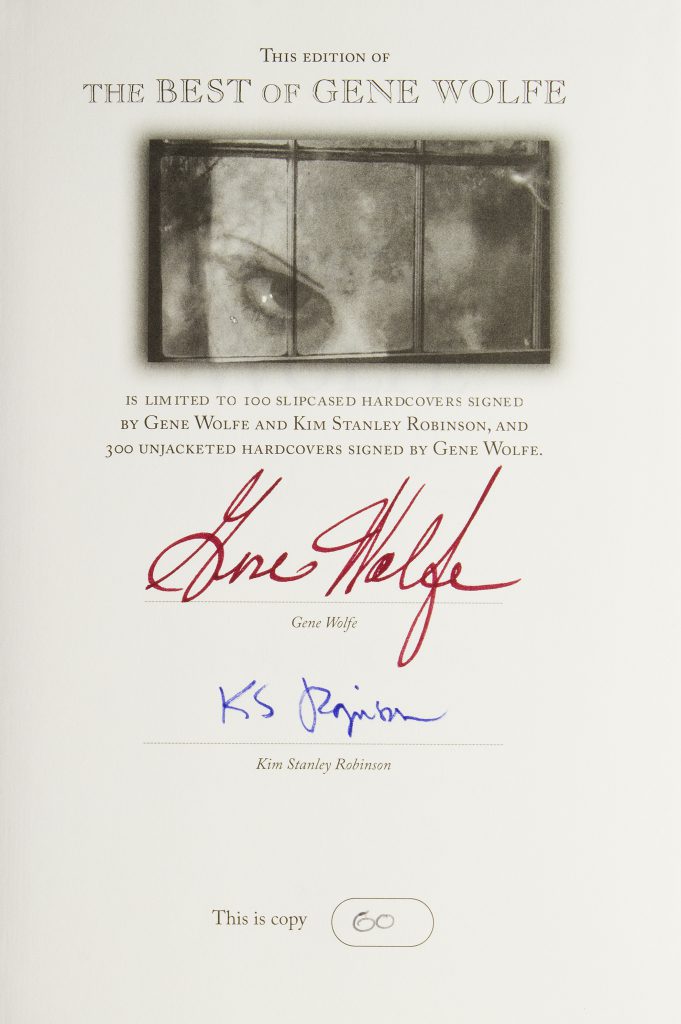

Gene Wolfe. The Very Best of Gene Wolfe. A Definitive Retrospective of His Finest Short Fiction. Hornsea, East Yorkshire: PS Publishing, 2009.

Collection of short stories by the legendary Gene Wolfe, the nimblest stylist at work in contemporary science fiction. Wolfe’s novels include multi-volume series dense with meaning, and several works that interrogate the nature of genre literature: fantasy, pirate fiction, pulp adventure, and science fiction. This applies equally to the short fiction: it is tricky and indirect, rich in allusion and portent, and sometimes written with a simple clarity that nonetheless conceals as much as it discloses.

One of 100 copies signed by Wolfe and Kim Stanley Robinson, who wrote the introduction.

No. 68.

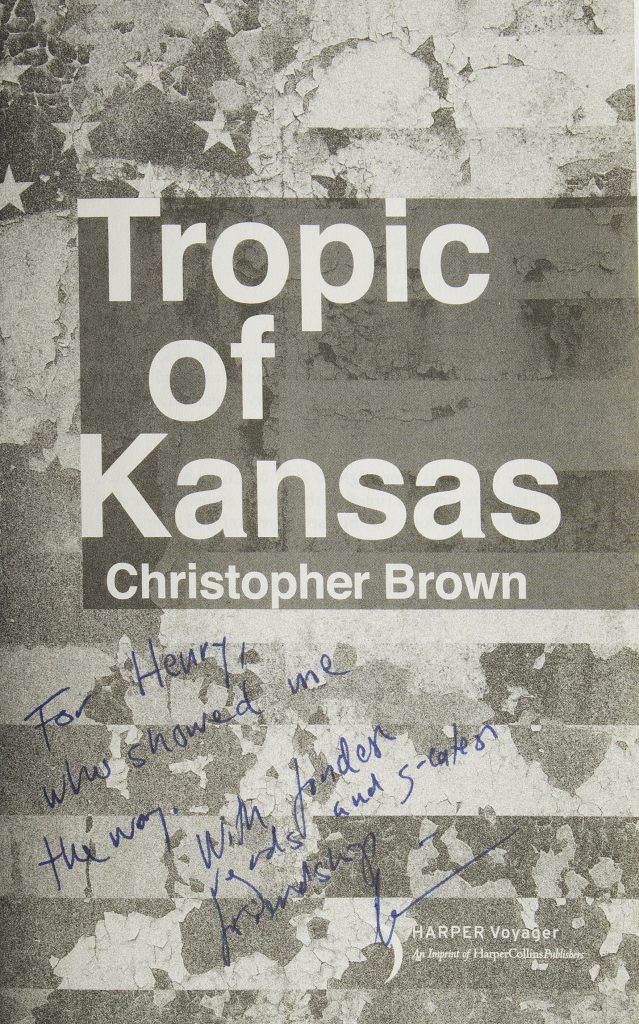

Christopher Brown. Tropic of Kansas. New York: Harper Voyager, April 2017.

“It had been an emergency for as long as Tania could remember.”

Set in an alternate USA riven by political strife, ecological and economic collapse, Tropic of Kansas is a novel of a new world coming into being: dark, nimble, hilarious, deeply alarming, truly American.

Proof copy, presentation inscription from the author:

“For Henry who showed me the way . . .”

No. 70.

Contents

Introduction

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed