John Crowley. Little, Big. New York: Bantam, 1981.

John Crowley’s masterpiece is many novels, all of them a single tale, made of family and story and time. Little, Big is a multi-generational novel of an American family told in three intricately braided love stories. It is a tale of the porous boundaries between our world and the elsewhere of the fairy folk. The book is a dark dystopian account of the rise of an American demagogue as the nation’s infrastructure and institutions crumble. It also plays a nimble and sophisticated game with four hundred years of literature, from Shakespeare and Mother Goose to Alice in Wonderland and Thornton W. Burgess.

Little, Big is my favorite work of fiction, a book I have read and reread many times.

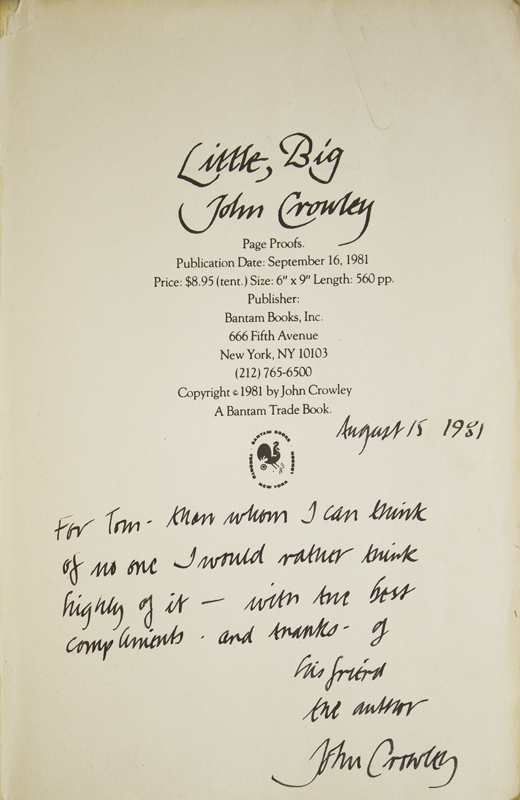

Proof copy, inscribed by the author to Thomas M. Disch.

No. 50.

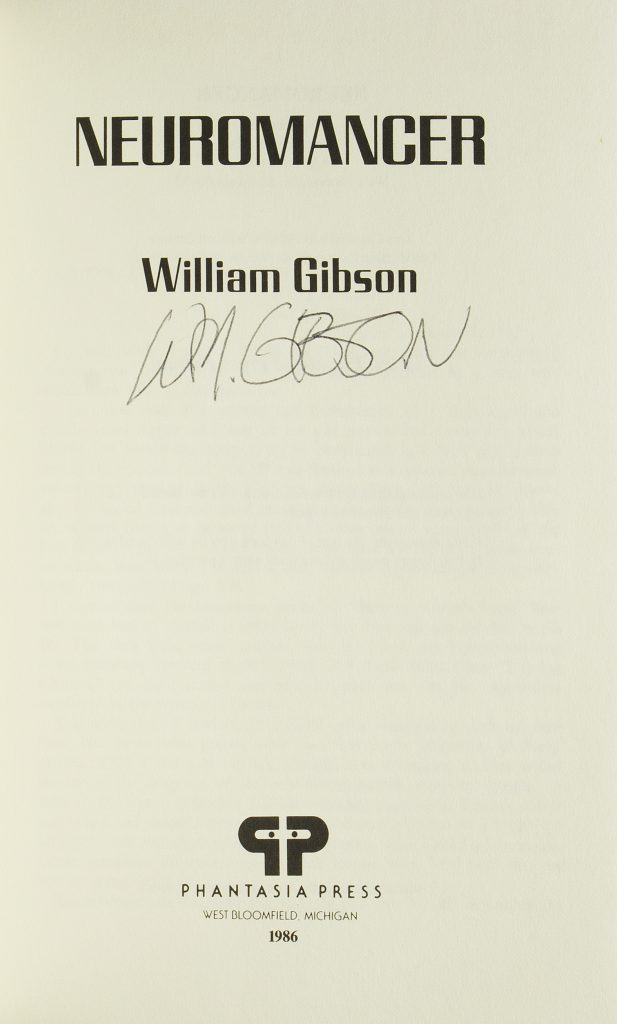

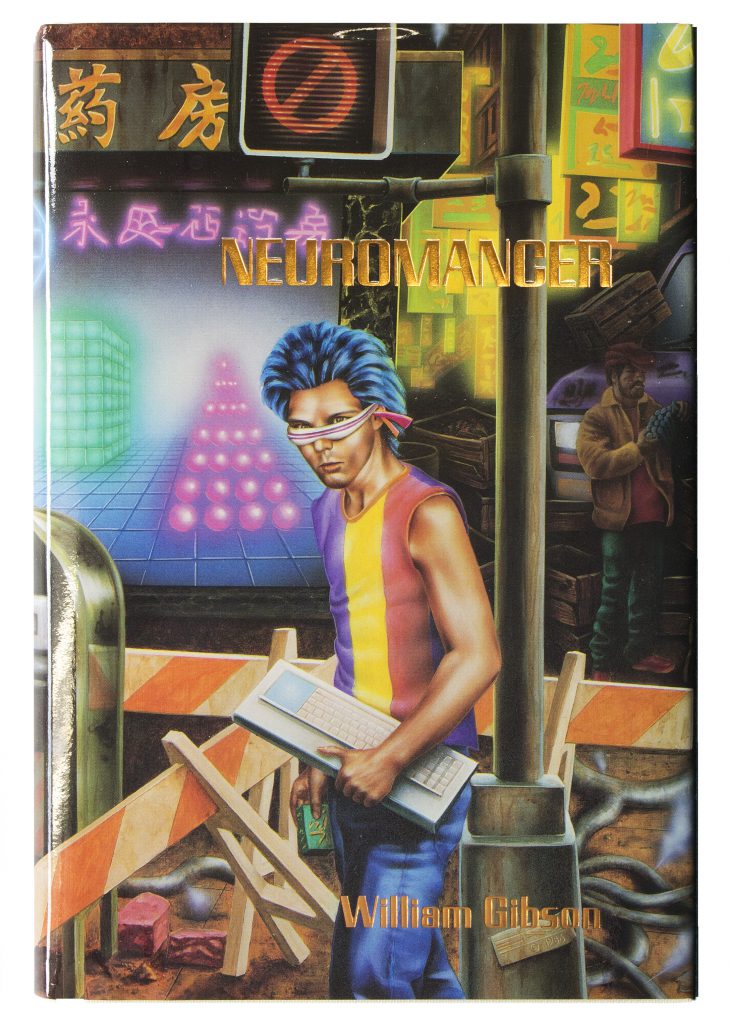

William Gibson. Neuromancer. West Bloomfield, Michigan: Phantasia Press, 1986.

Neuromancer was published as a paperback original in 1984. The world of the novel is a near-future urban sprawl, and the protagonists are computer-savvy lowlifes linking themselves into the matrix of data. The power structures the outlaw Case encounters are wealthy, untouchable, and not merely cosmopolitan, but post-national and post-human artificial intelligences residing on satellite colonies in orbit around the Earth. The prose is as clear and compelling as Raymond Chandler’s, and Neuromancer took the world of science fiction by storm.

First American hardcover edition, signed by the author.

No. 51.

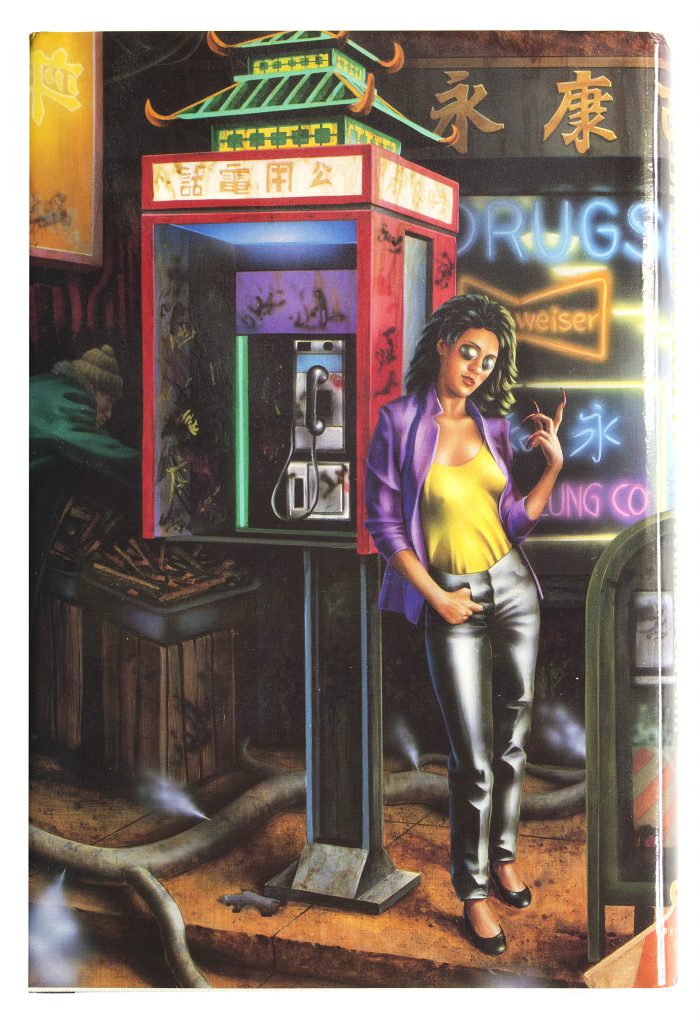

William Gibson. Neuromancer. West Bloomfield, Michigan: Phantasia Press, 1986. Pictorial dust jacket.

Note the kinetic, and high-information painting by Barclay Shaw for the dust jacket: the scene is neon post-Bowie noir, full of urban menace and suggestion, with semiotic teasers and colored geometries. On this back panel, a young woman with artificial eyes leans against a pay phone.

The dust jacket is not the text but the context of the book. Bibliography, like science fiction, as close observation of the present.

No. 51.

William Gibson. Neuromancer. West Bloomfield, Michigan: Phantasia Press, 1986. Pictorial dust jacket.

Note the kinetic, and high-information painting by Barclay Shaw for the dust jacket: the scene is neon post-Bowie noir, full of urban menace and suggestion, with semiotic teasers and colored geometries. On this front panel, a young man holds a keyboard.

The dust jacket is not the text but the context of the book. Bibliography, like science fiction, as close observation of the present.

No. 51.

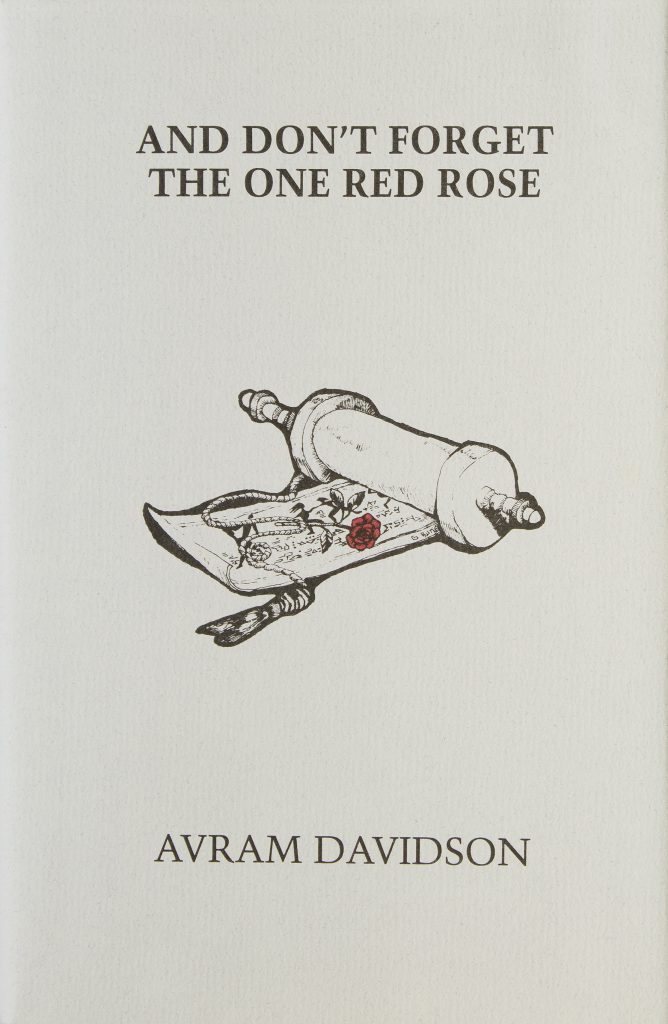

Avram Davidson. And Don’t Forget the One Red Rose. Seattle: Dryad Press, 1986.

Avram Davidson (1923–93) is an American master of the short story who remains, twenty-five years after his death, almost unknown inside and outside the world of science fiction. The best of his short fiction was collected in The Avram Davidson Treasury (1998). His nonfiction, some of it collected in Adventures in Unhistory (1993), is like no one else’s: digressions and narrative zigzags abound.

And Don’t Forget the One Red Rose is a story of an immigrant bookseller with very unusual books (and even more unusual prices), first published in Playboy in 1975.

No. 52.

Avram Davidson. And Don’t Forget the One Red Rose. Seattle: Dryad Press, 1986.

One of 15 hardcover copies signed by the author.

No. 52.

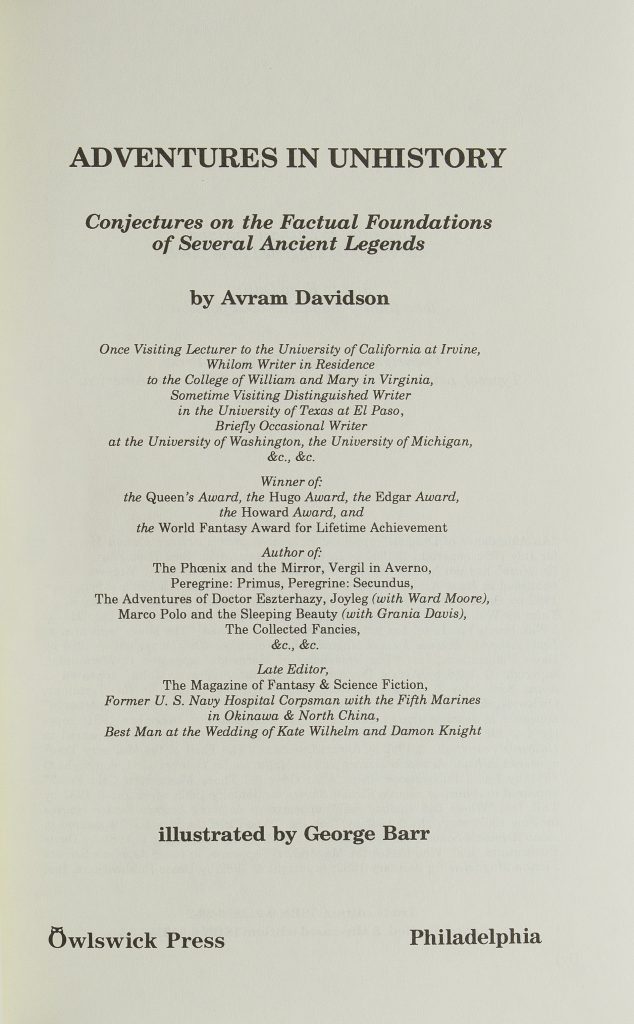

Avram Davidson. Adventures in Unhistory. Conjectures on the Factual Foundations of Several Ancient Legends [etc.]. Philadelphia [i.e., King of Prussia, Penna.]: Owlswick, 1993.

No. 52.

Avram Davidson. Adventures in Unhistory. Conjectures on the Factual Foundations of Several Ancient Legends [etc.]. Philadelphia [i.e., King of Prussia, Penna.]: Owlswick, 1993.

Publisher George Scithers’ copy, no. 1 of 72 numbered copies signed by the author and artist George Barr.

No. 52.

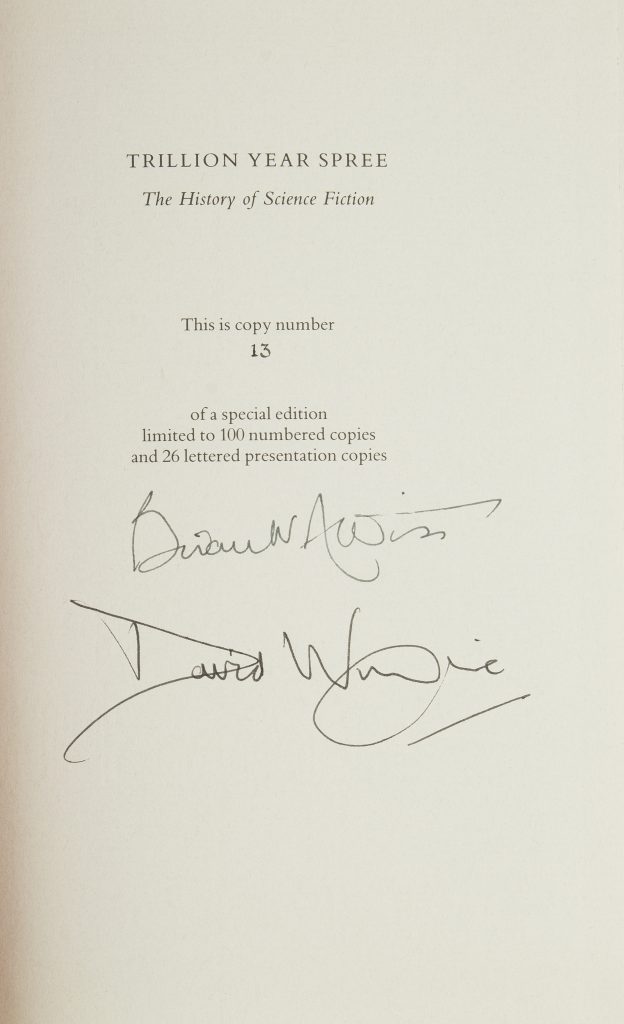

Brian W. Aldiss, with David Wingrove. Trillion Year Spree. The History of Science Fiction. London: Gollancz, 1986.

In 1973, Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) published Billion Year Spree, a history of the field notable for its advocacy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the key text in science fiction. This expanded edition is a colorful and often funny book, with portraits of writers, written by an “impartial insider,” who had been at the heart of British science fiction since the mid-1950s.

No. 53.

Brian W. Aldiss, with David Wingrove. Trillion Year Spree. The History of Science Fiction. London: Gollancz, 1986.

In 1973, Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) published Billion Year Spree, a history of the field notable for its advocacy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the key text in science fiction. This expanded edition is a colorful and often funny book, with portraits of writers, written by an “impartial insider,” who had been at the heart of British science fiction since the mid-1950s.

One of 100 numbered copies, signed by the authors, with an introduction by Aldiss not published in the trade edition.

No. 53.

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. The Difference Engine. London: Gollancz, 1990.

In The Difference Engine, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling took the punk attitudes and the ideas of computer-induced social change and went back in time to write an alternate history. The novel charts a digital society based upon the successful exploitation of the analytical engines of Charles Babbage. The disruptions to the Victorian world order are plain to see and point to a panopticon surveillance society. Other writers had been working on alternate Victorian and Edwardian worlds, including K. W. Jeter (who coined the term “steampunk” in 1987), James P. Blaylock, and Rudy Rucker.

Tom Disch praised The Difference Engine as “genre-transcending,” and with this book steampunk caught the popular imagination. In the last decade steampunk has leapt the fence from science fiction to carry a wider meaning in fashion and visual style.

No. 54.

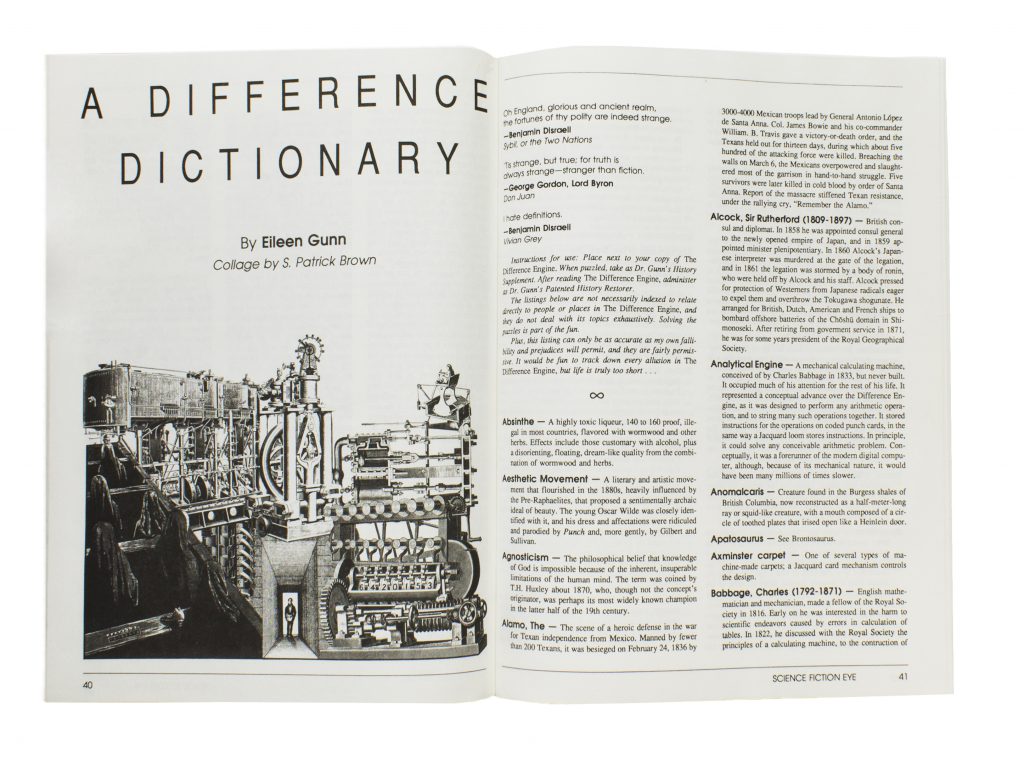

Eileen Gunn. “A Difference Dictionary,” [in:] Science Fiction Eye 8, Winter 1991.

Eileen Gunn’s gloss on Gibson and Sterling’s The Difference Engine, in an issue of the smart and stylish critical magazine Science Fiction Eye.

No. 54.

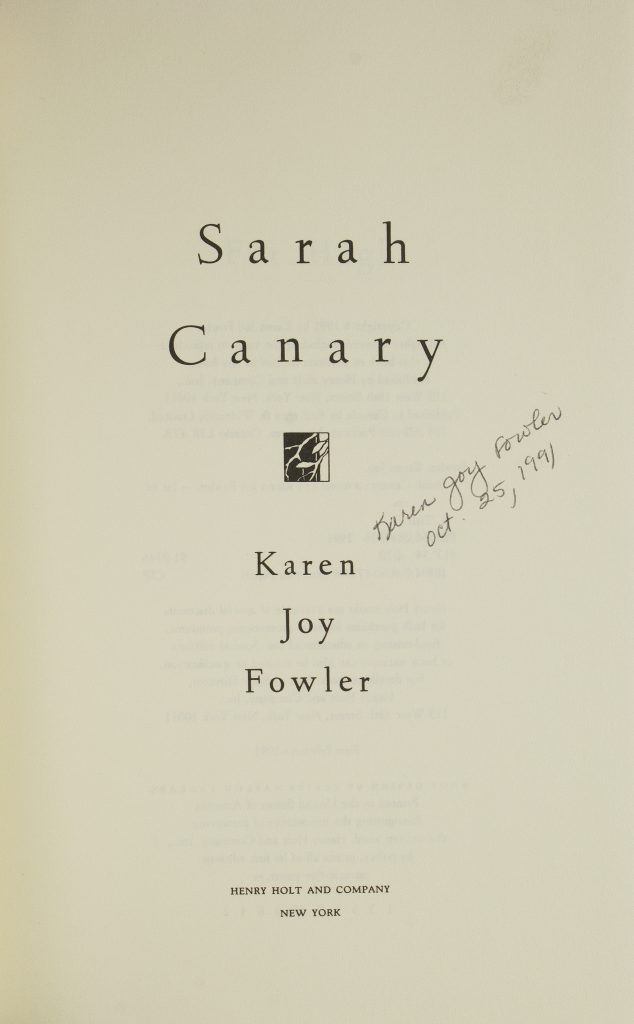

Karen Joy Fowler. Sarah Canary. New York: Henry Holt, 1991

Sarah Canary is a first contact tale set in late nineteenth-century America. A strange, badly dressed white woman, with “skin poreless and polished,” shining like porcelain, appears near an itinerant railway workers’ camp in the woods of Washington. No one, not even a polyglot Chinese man, can understand her speech. She is confined to an asylum. “As an emblem of the enigma behind the idea of first contact she is perhaps definitive. As a dramatization of the self-deluding imperialisms of knowledge, Sarah Canary is equally convincing” (SFE). Fowler is also author of The Jane Austen Book Club (2004).

No. 55.

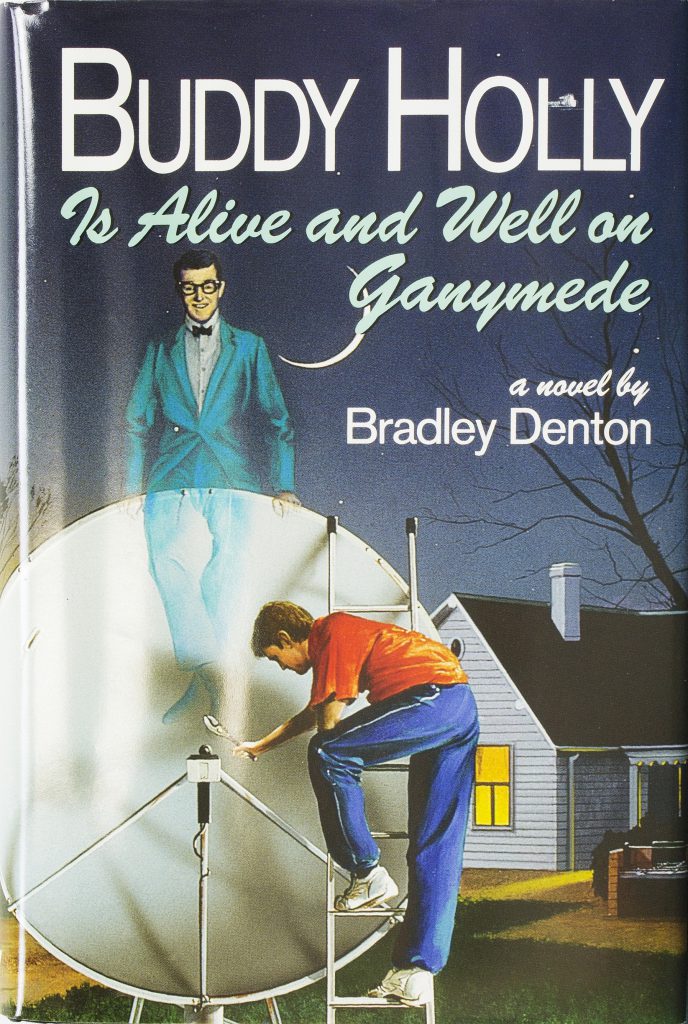

Bradley Denton. Buddy Holly Is Alive and Well on Ganymede. New York: Morrow, 1991.

Rock ’n’ Roll and science fiction, American style.

Bradley Denton’s great comic novel, Buddy Holly Is Alive and Well on Ganymede, is the tale of the hapless loner Oliver Vale, movie buff, motorcyclist, and child of rock ’n’ roll living in northeast Kansas. While whanging his Sky-Vue satellite dish with a crescent wrench in hope of a better TV signal, Vale finds himself at the center of a galactic power struggle. Buddy Holly, who died in a plane crash in 1959, is broadcasting to every television on the planet, and mentioning Vale’s name and address in between songs.

Denton’s Buddy Holly won the John W. Campbell award for best novel.

No. 56.

Bradley Denton. Buddy Holly Is Alive and Well on Ganymede. New York: Morrow, 1991.

Rock ’n’ Roll and science fiction, American style.

Signed by the author.

Denton’s Buddy Holly won the John W. Campbell award for best novel.

No. 56.

Timothy d’Arch Smith. Alembic. A Novel. Normal, Ill.: Dalkey Archive Press, 1992.

Rock ’n’ Roll and science fiction, British style.

The science in London antiquarian bookseller Timothy d’Arch Smith’s Alembic is early modern alchemy in the service of a modern bureaucratic state, and the rock ’n’ roll is Celestial Praylin, a band on the scale of Led Zeppelin. The antics of Nicholas Sparks, depraved megastar frontman of Celestial Praylin, the crazed adoration of the fans, and the scary manipulations of the government office of experimental alchemy are reported through the eyes of Thomas Graves. Graves is an antiquarian bookman, and the sort of overly sensitive, self-centered post-adolescent person who is the ultimate novel protagonist — so long as he survives the events and grows up to tell the tale.

The author portrait is by Duncan Andrews. Signed by the author on the title page, inscribed on the first blank, “To the Man Ray of Lexington Avenue . . .”; also signed by Duncan Andrews on the flyleaf, and with his original color photograph of the author.

No. 57.

Wendy Walker. The Secret Service. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon, 1992.

The Secret Service tells the story of an elaborate nineteenth-century Catholic conspiracy against the English monarchy, complete with dastardly continental noblemen — aesthetes of prodigious sophistication and guile — and a mysterious heiress sequestered in a tower impregnable. Walker’s astonishing conceit is that the three principal British agents of the eponymous secret service have the capacity to transform themselves into objects, the better to spy upon the conspirators: a crystal wine goblet, a salmon rose swaying where there is no breeze; and a bronze statue. Mind and perception are dependent upon the form of their container and Walker gives us the altered sensibilities of the spies. This is the great underrated book of the 1990s.

No. 58.

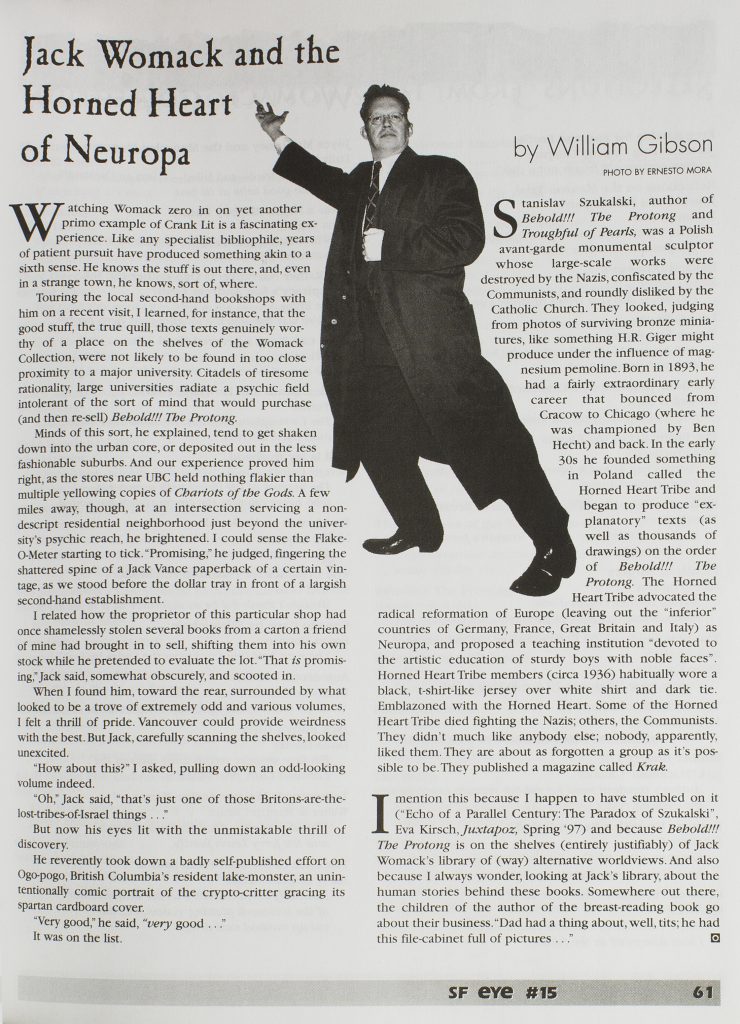

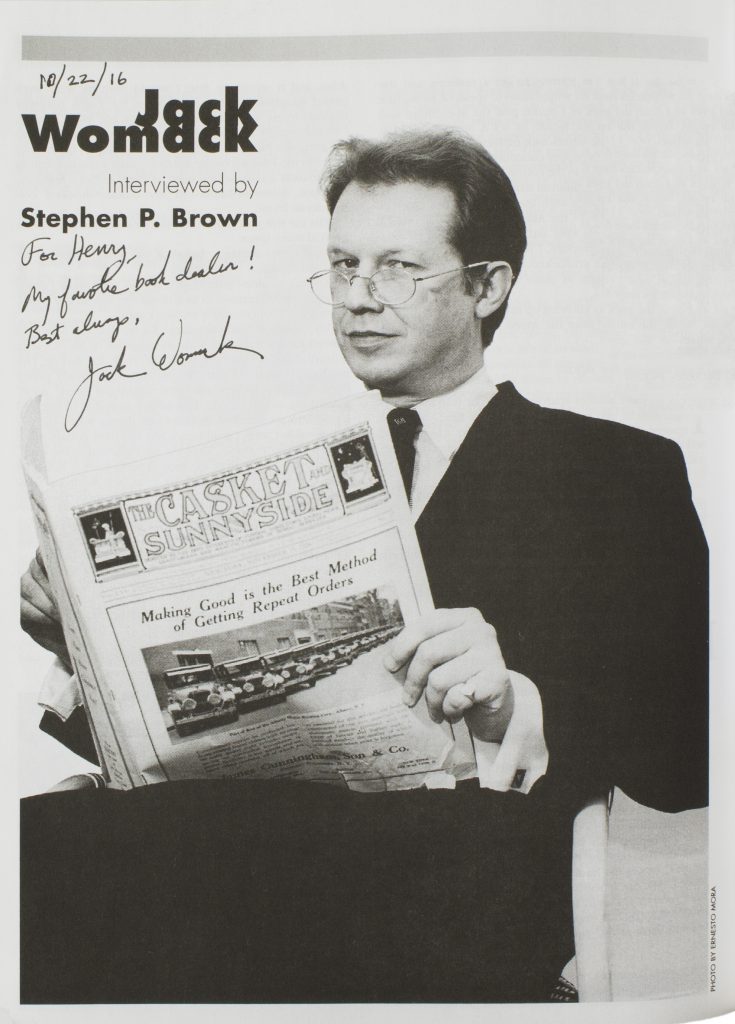

Jack Womack interviewed by Stephen P. Brown, [and:] William Gibson interviewed by Jack Womack, [in:] SF Eye Issue #15. Asheville, North Carolina: SF Eye, Fall 1997.

The final issue of this stylish magazine, with a great interview of William Gibson by Jack Womack, open at “the World Before Television.”

This issue has a feeling of “the world before the internet,” though some of us were already online by 1997. Much of the critical conversation now occurs online, but how will such digital material survive?

No. 59.

Jack Womack interviewed by Stephen P. Brown, [and:] William Gibson interviewed by Jack Womack, [in:] SF Eye Issue #15. Asheville, North Carolina: SF Eye, Fall 1997.

Jack Womack, Kentucky-born and resident in New York since the 1970s, published a series of scathing novels of corporate capitalism unleashed. Ambient (1987) and its successors are a portrait of America as Saturn devouring his own children. Womack’s ear for American speech is as acute as his ability to chronicle dystopia while it is occurring. Womack’s gravelly drawl and sardonic humor are part of American science fiction.

No. 59.

Jack Womack interviewed by Stephen P. Brown, [and:] William Gibson interviewed by Jack Womack, [in:] SF Eye Issue #15. Asheville, North Carolina: SF Eye, Fall 1997.

Inscribed by Jack Womack.

No. 59.

John Clute and John Grant, editors. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

John Clute, Canadian-born author long resident in London, is a brilliant critic of science fiction and what he calls “fantastika,” or “that wide range of fictional works whose contents are understood to be fantastic.”

To produce an Encyclopaedia is essentially a political act: to strike a spark into the tinder-dry edifice of the ancien régime (in the case of Diderot’s Encyclopédie), or, in the case of The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, to throw open the doors of the labyrinth and propose a new way of approaching the literature of the fantastic. Clute embeds a revolutionary vocabulary of criticism within The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, in such entries as Polder, Thinning, Belatedness, Arabian Nightmare, Crosshatch, Little, Big, and Recognition.

Clute is also the prime mover of the vast and authoritative Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (or SFE), now an online resource. It is impossible to consider the recent history of the field without encountering Clute’s ideas and writings.

No. 60.

John Clute. The Darkening Garden. A Short Lexicon of Horror. Seattle: Payseur & Schmidt, 2006.

With: Postcards of Doom. A Journey from Affect to Vastation. Thirty artists, thirty motifs. Seattle: Payseur & Schmidt, 2006.

The Darkening Garden builds upon Clute’s distinctive critical vocabulary, and its definitions are so rich in allusion that it functions as an encyclopaedia in miniature. In its discussion of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Clute demonstrates his willingness to reassess earlier findings. This edition was illustrated by thirty artists, each illustrating a descriptive term. The Postcards of Doom reproduce the illustrations and were issued as a set in conjunction with The Darkening Garden.

No. 60.

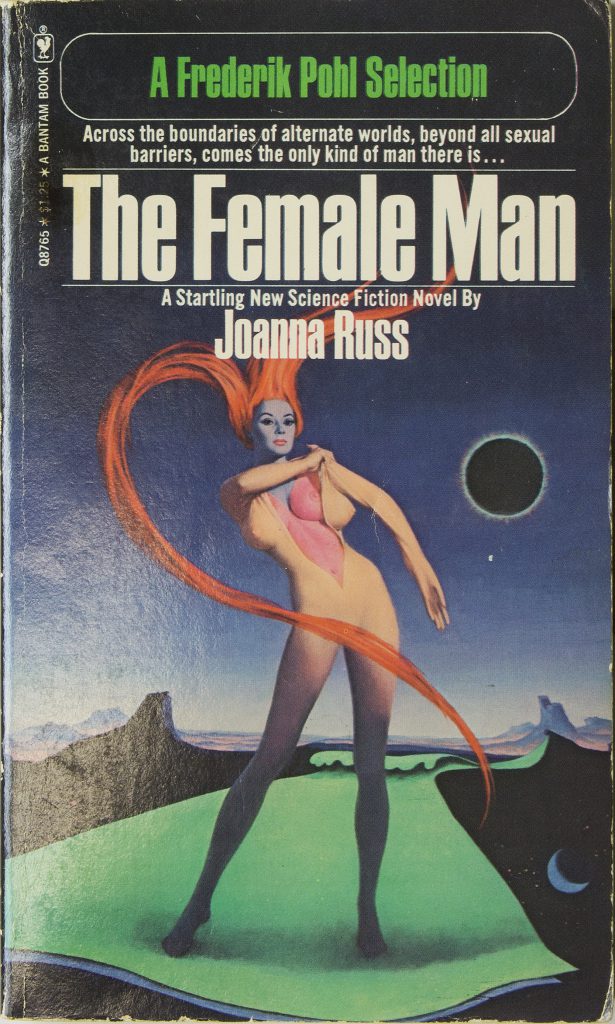

Joanna Russ. The Female Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1975.

“In 1975 Russ published The Female Man, which must be accounted the best feminist science-fiction novel of all time [. . .] Russ wants to empower women.”

— Thomas M. Disch

A novel of life on the women’s planet Whileaway, in the form of four linked stories in which alternate versions of the protagonist move from servility to liberation.

No. 61.

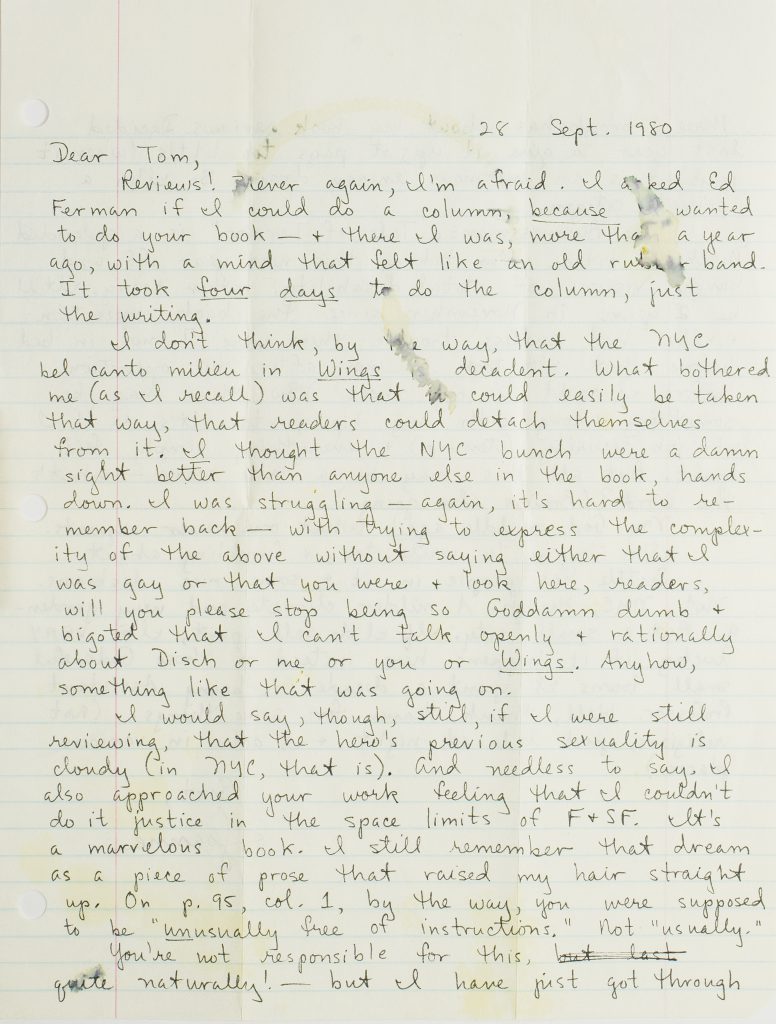

Joanna Russ. Autograph Letter, signed, to Thomas M. Disch, 28 September 1980.

Joanna Russ (1937–2011) is the rainy night sky when the whole box of fireworks goes up at once, a blazing angel saying, Look! She was one of the fiercest intellects in science fiction in the 1960s and 1970s, a writer of excellent short fiction and one of the best critics of contemporary work and earlier authors. Ill health largely curtailed her fiction and critical writing after the early 1980s.

She writes her friend Tom Disch, whose novel On Wings of Song (1979) she had just reviewed: “Reviews! Never again, I’m afraid.”

No. 61.

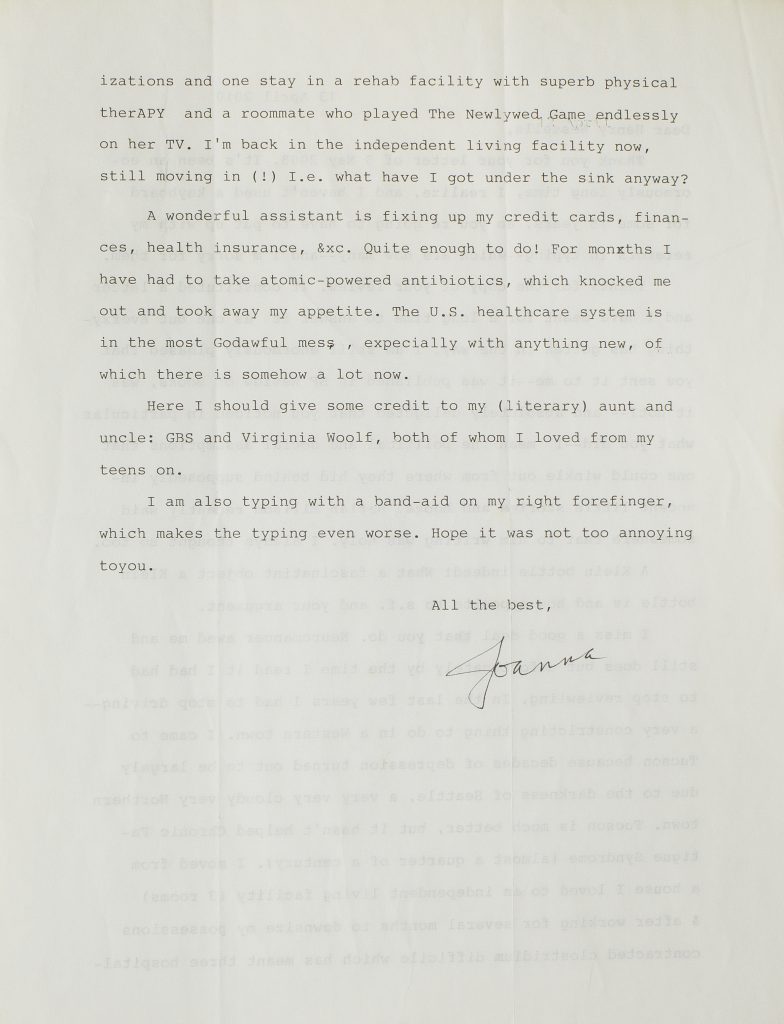

Joanna Russ. Typed Letter, signed, to Henry Wessells, 13 April 2010.

“What a fascinating object a Klein bottle is and how apposite to s.f. and your argument. [. . .] Neuromancer awed me and still does but unfortunately by the time I read it I had to stop reviewing.”

No. 61.

Contents

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed