Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. Introduction by Francis Wyndham. London: Andre Deutsch, 1966.

I include Wide Sargasso Sea in the literatures of the fantastic because it is, quite simply, a pioneering work. What Rhys accomplishes is a perfect example of the critical fiction: a writer’s artistic response to another work of literature. This short novel of the life of a Creole heiress to lands in Jamaica and Dominica is an indictment of a legal system that assigns a wife’s money and properties to the fortune-hunting husband; it is also the story of the first Mrs. Rochester of Jane Eyre.

No. 35.

Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. Introduction by Francis Wyndham. London: Andre Deutsch, 1966.

Title page of the first edition.

No. 35.

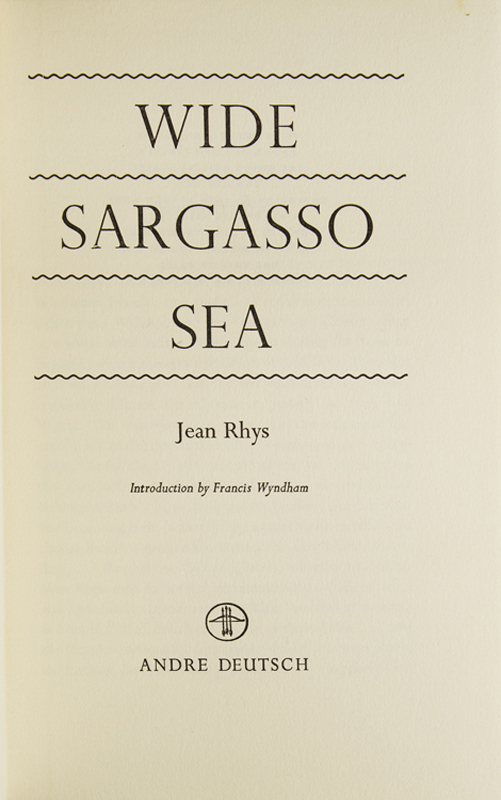

Samuel R. Delany. Babel-17. New York: Ace Books, [1966].

Signed by the author.

No. 36.

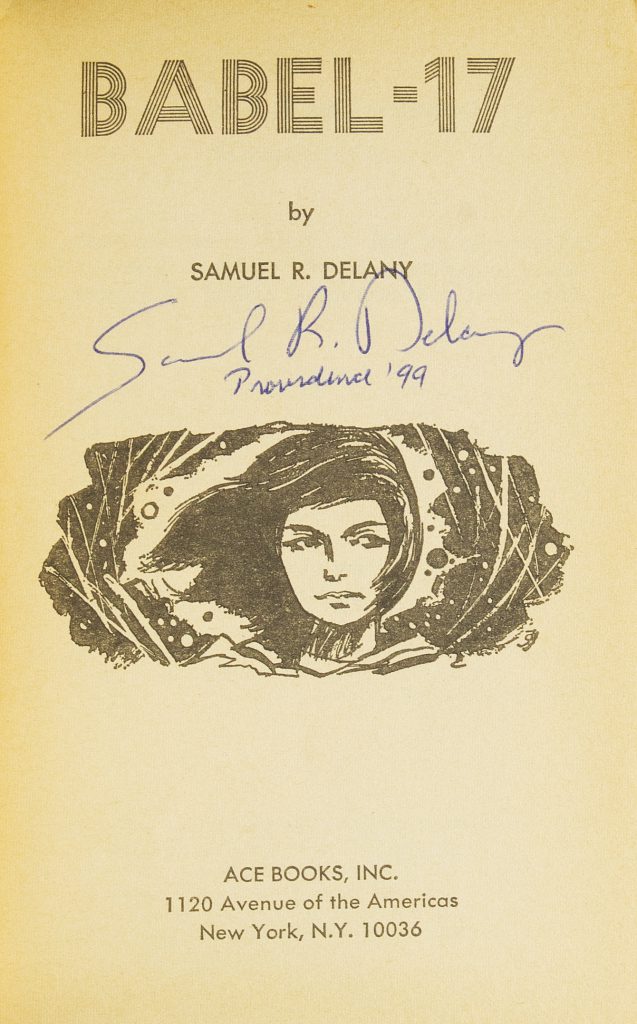

Samuel R. Delany. Babel-17. New York: Ace Books, [1966].

Nebula award-winning novel by African American author and polymath Samuel R. Delany, whose early works established him as one of the major writers in the field. Babel-17 is a tale of intergalactic war, with language used as a weapon, and only the poet Rydra Wong is adequate to the task of preventing sabotage and invasion.

No. 36.

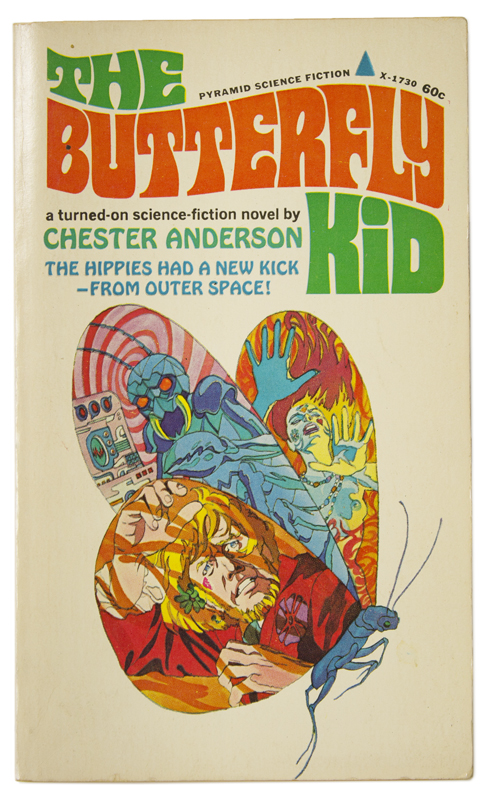

Chester Anderson. The Butterfly Kid. New York: Pyramid Books, 1967.

Small book, big ripples: Chester Anderson used the $300 advance from his science fiction novel The Butterfly Kid to buy a Gestetner printing machine and set himself up as printer to the Diggers and the Summer of Love. In “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Joan Didion chronicled her search for “the Connection” in San Francisco in 1967: Anderson was the figure of mystery whom Didion sought but never found.

The Butterfly Kid is a novel of alien invaders distributing a new drug that can alter reality. It also, as Eileen Gunn observed, “tells the unvarnished truth about what it was like to be a 34-year-old hipster trapped in hippie New York with the Fugs in 1966!

No. 37.

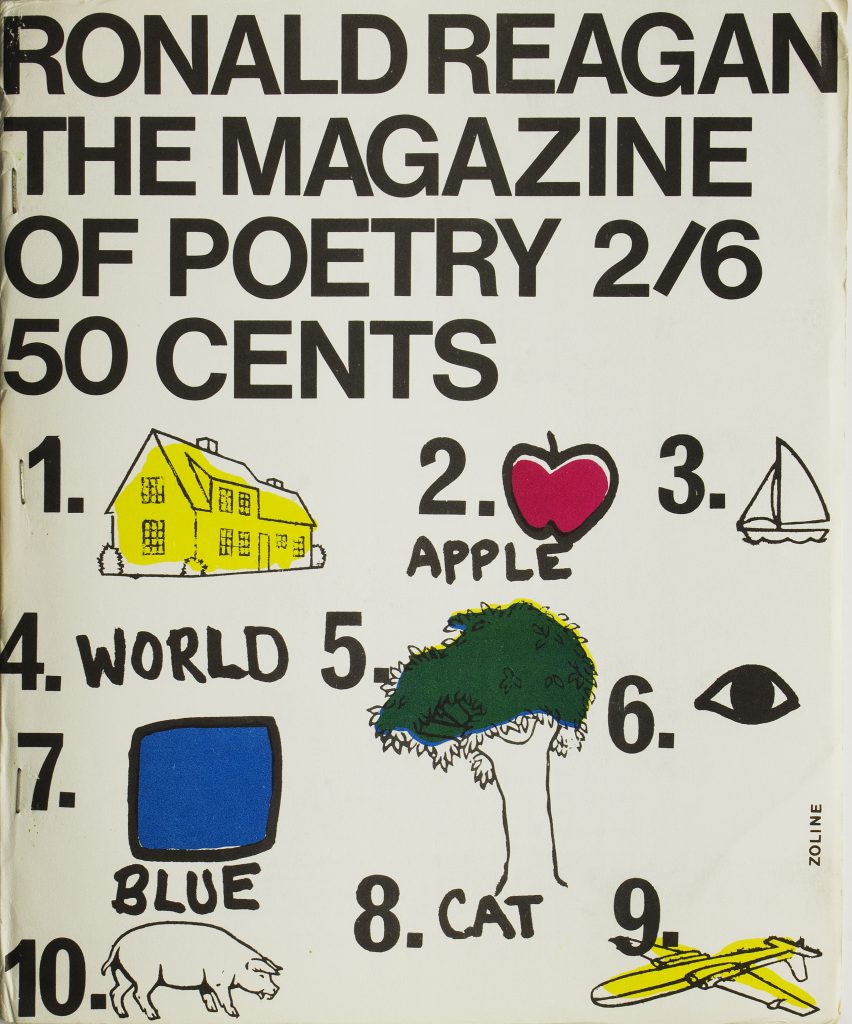

John Sladek, Pamela Zoline, and Thomas M. Disch. Ronald Reagan The Magazine of Poetry. London, 1968.

John Sladek, satirist, laughing fatalist, and “the high priest of something else,” and his flatmates published this poetry, protest, and science fiction ’zine at the intersection of the Anglo-American literary avant-gardes, the New York East Village scene and British New Wave. The magazine includes J. G. Ballard’s obscene satire on Ronald Reagan, then serving as governor of California.

Pictorial wrappers by Sladek and Zoline. Provenance: Thomas M. Disch, contributing editor.

No. 38.

John Sladek, Pamela Zoline, and Thomas M. Disch. Ronald Reagan The Magazine of Poetry. London, 1968.

Pictorial wrappers by Sladek and Zoline.

No. 38.

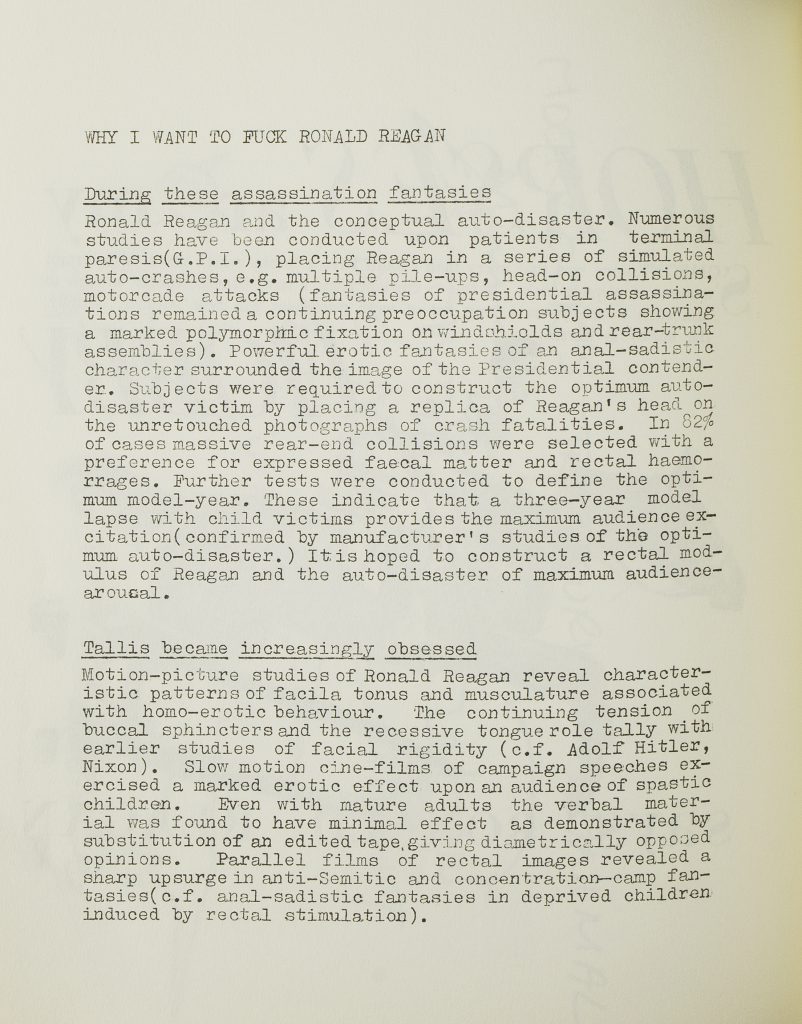

(J. G. Ballard) Ronald Reagan The Magazine of Poetry. London, 1968.

Another copy, open to J. G. Ballard’s dark and prescient satire.

No. 38.

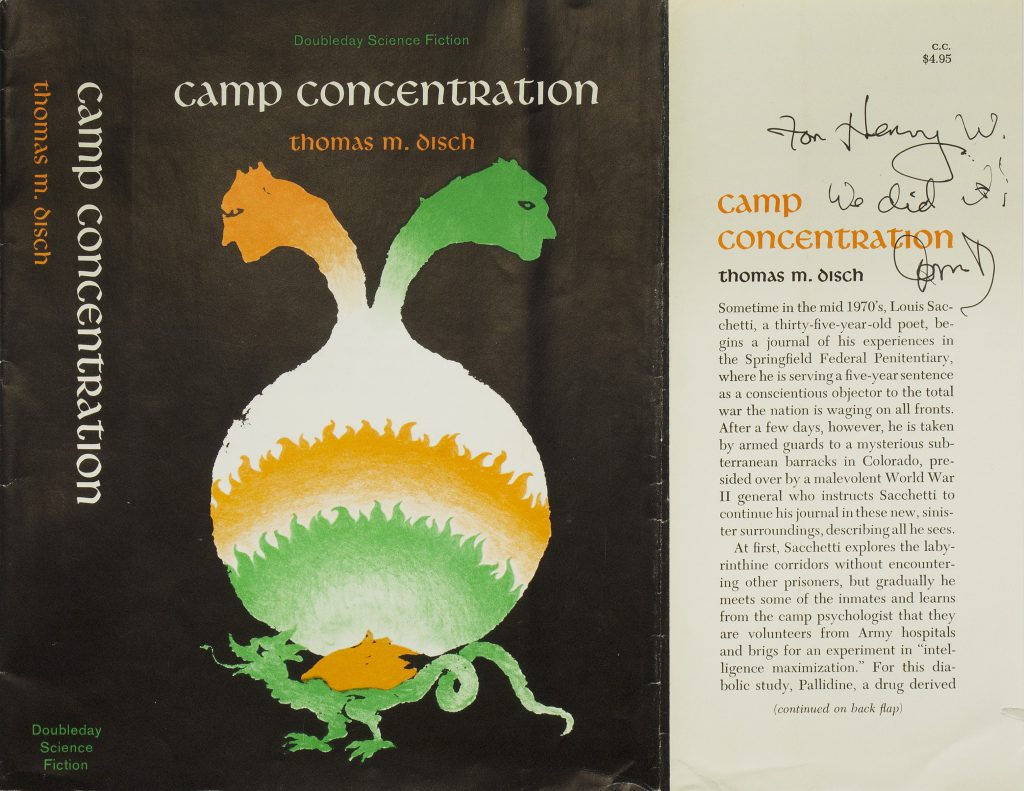

Thomas M. Disch. Camp Concentration. Garden City: Doubleday, 1969.

Camp Concentration is a savage satire of American conformity, with allusions to Faust, Aquinas, and alchemy. Imprisoned as a conscientious objector, poet Louis Sacchetti is soon transferred to a medical experimentation center where he is injected with Pallidine, a drug that increases human intelligence but invariably causes death from syphilis. Sacchetti experiences intellectual ecstasy, even while he sees that he and his fellow prisoners are being used by their wardens. A concise, brilliant novel.

No. 39.

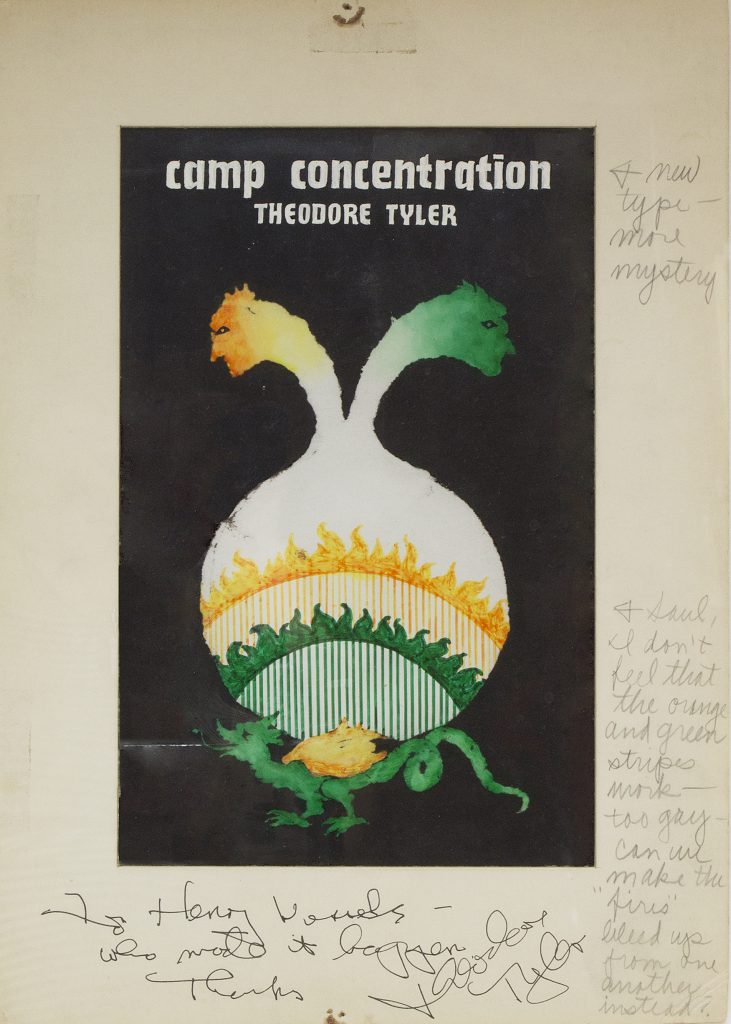

(Thomas M. Disch) Saul Lambert. Camp Concentration Theodore Tyler. Mock-up of cover art, marked for revisions. [New York, 1969].

Dust jacket art for the American edition of Camp Concentration, later inscribed by Disch, also signed by him in jest as “Theodore Tyler.”

No. 39.

Thomas M. Disch. Camp Concentration. Garden City: Doubleday, 1969.

Proof copy of the Doubleday dust jacket, signed by Disch.

No. 39.

James Blish. Doctor Mirabilis. A Novel. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1971.

“These were words of power.”

Doctor Mirabilis is a science fiction novel of the history of science, a fictional study of Roger Bacon, the thirteenth-century English monk, scientist, and philosopher. James Blish (1921-1975), author and critic, was interested in Bacon as the originator of the scientific way of thinking, which Blish called “the theory of theories as tools.” Blish’s visionary approach and the discovery that Bacon makes at the heart of the book (deciphering the dream-encoded formula for black powder) embody the notion of conceptual breakthrough central to science fiction.

Signed by the author on the title page.

No. 40.

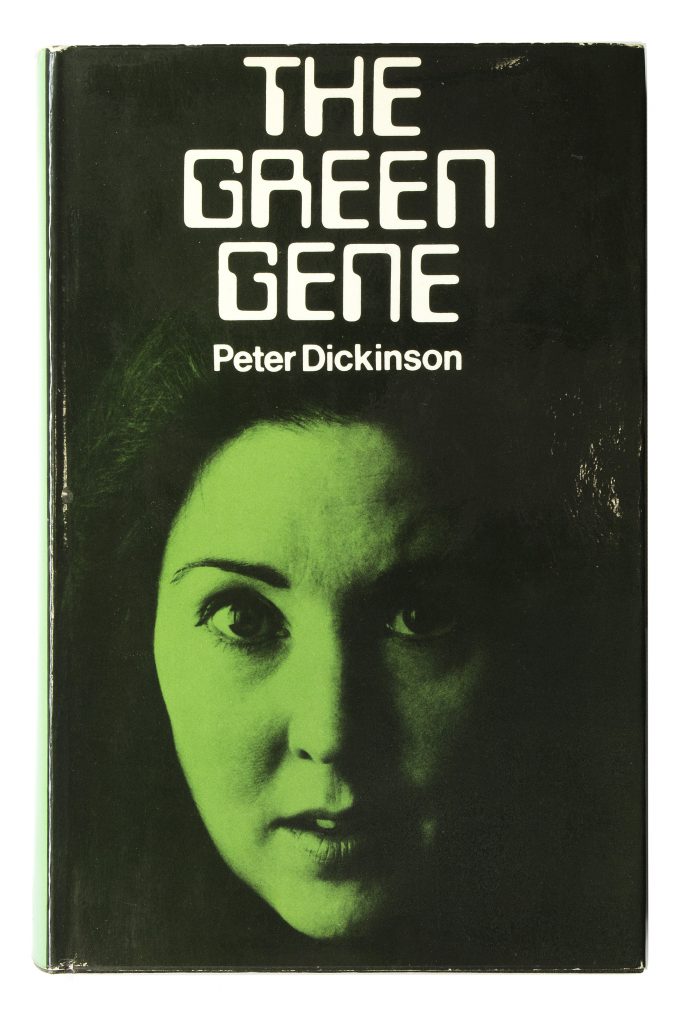

Peter Dickinson. The Green Gene. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1973.

The Green Gene is a comic satire of Anglo-Celtic relations that masks some brutal truths about English racism. It is indisputably science fiction because of the key roles that genetics, statistics, and computers play in the novel. A genetic accident, the Green Gene, has given all Celts green skin. At a time when there was no language available outside a subset of mathematics to describe computer programming, and in a Britain with only two sophisticated computers (one at the Race Relations Board, the other at Treasury), The Green Gene is the earliest novel of computer hacking: terrorists introduce a “computer rat” to disrupt the function of the central computer and ultimately discredit the racist policies of the establishment.

No. 41.

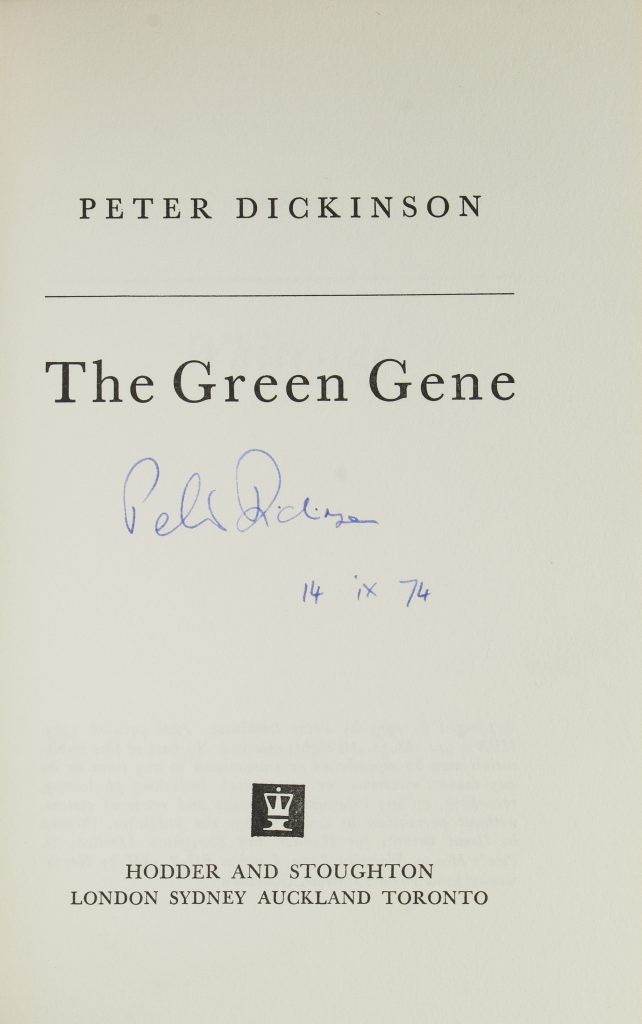

Peter Dickinson. The Green Gene. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1973.

Signed by the author on the title page.

No. 41.

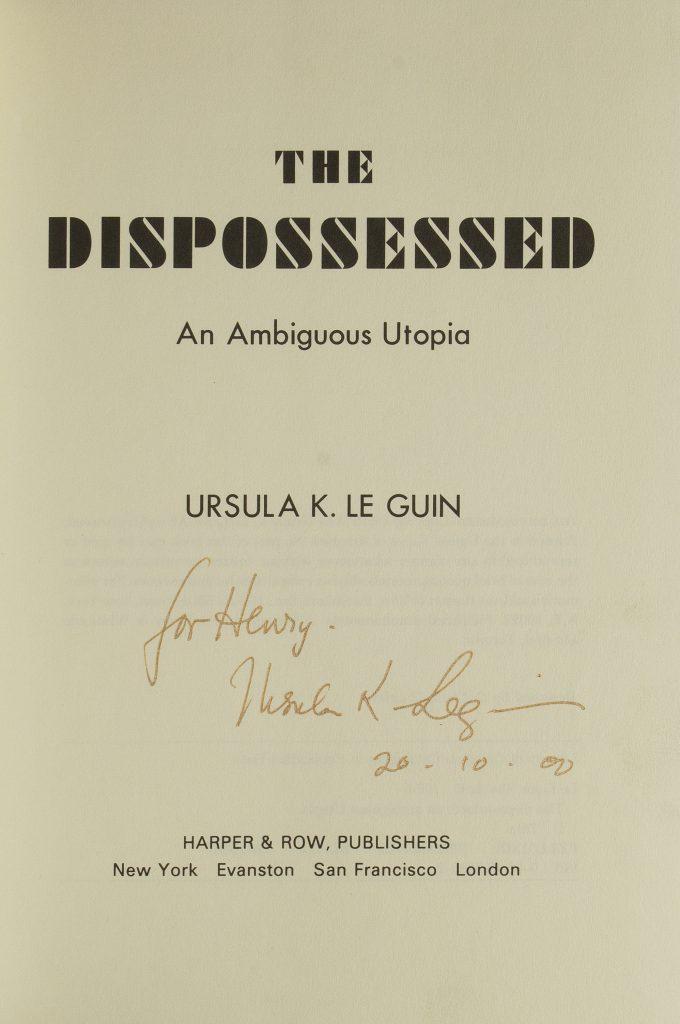

Ursula K. Le Guin. The Dispossessed. An Ambiguous Utopia. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Le Guin’s novel of a moon and its planet: the stark, almost desert-like world of the moon Annares, an anarchist cooperative society, and the much larger capitalist world of Urras. The book starts simply. “There was a wall. It did not look important.” Shevek, mathematician of Annares, arrives in Urras with nothing but his ideas, which are revolutionary. The Dispossessed won the Hugo and Nebula awards.

No. 42.

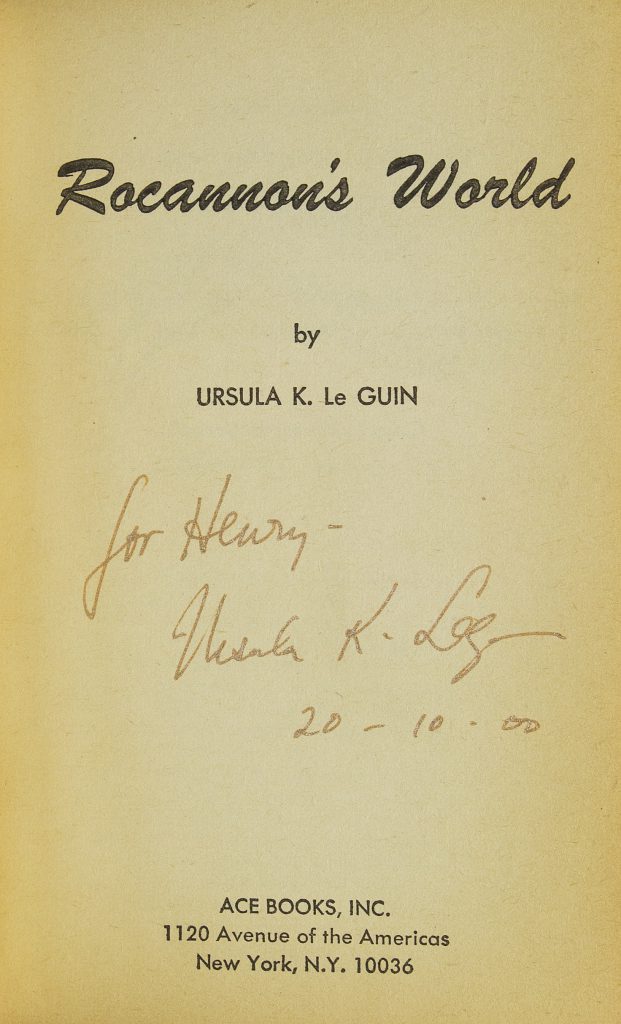

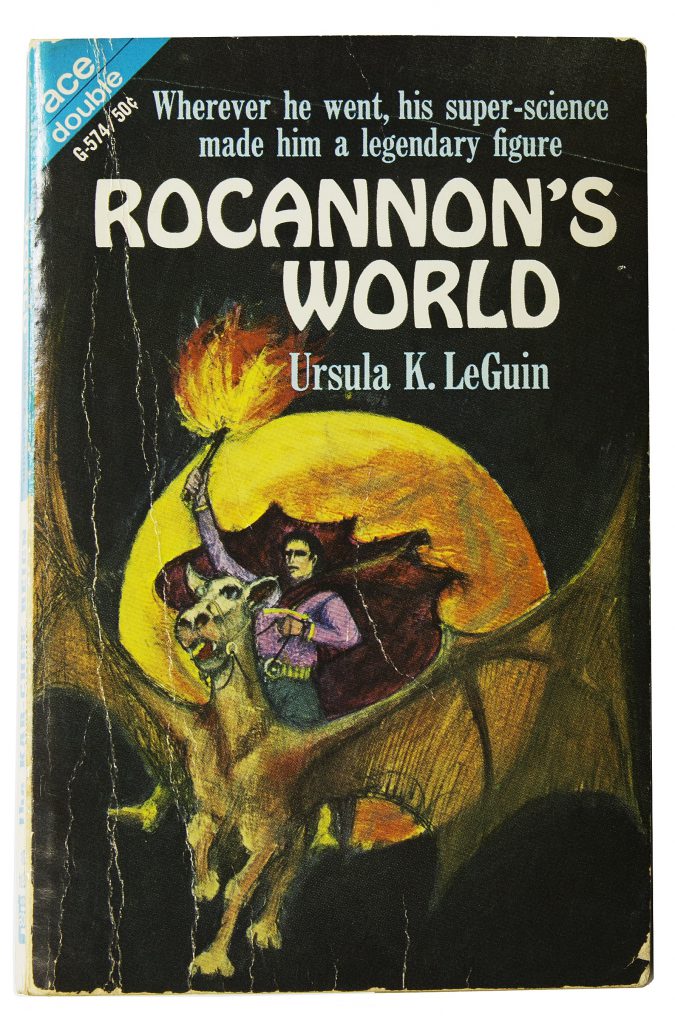

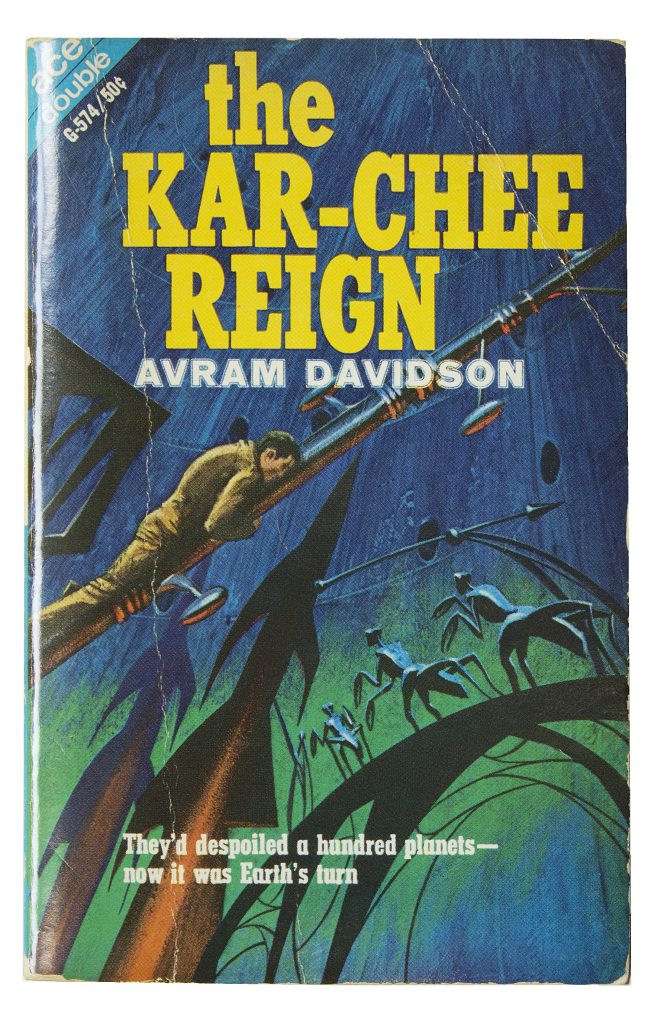

Ursula K. Le Guin. Rocannon’s World. New York: Ace Books, 1966. Ace Double G-574. Bound with: Avram Davidson. The Kar-Chee Reign.

Inscribed by the author on the title page.

No. 42.

Ursula K. Le Guin. Rocannon’s World. New York: Ace Books, 1966. Ace Double G-574. Bound with: Avram Davidson. The Kar-Chee Reign.

Ursula K. Le Guin (born 1929) wrote extensively during the 1950s, but she found her way into print when Cele Goldsmith, editor of Amazing Stories and Fantastic magazines from 1958 to 1965, bought her fantastical stories. Le Guin expanded “The Dowry of Angyar” (1964) into Rocannon’s World, her first book, published as an Ace Double paperback original.

No. 42.

Ursula K. Le Guin. Rocannon’s World. New York: Ace Books, 1966. Ace Double G-574. Bound with: Avram Davidson. The Kar-Chee Reign.

The other half of the Ace Double paperback.

No. 42.

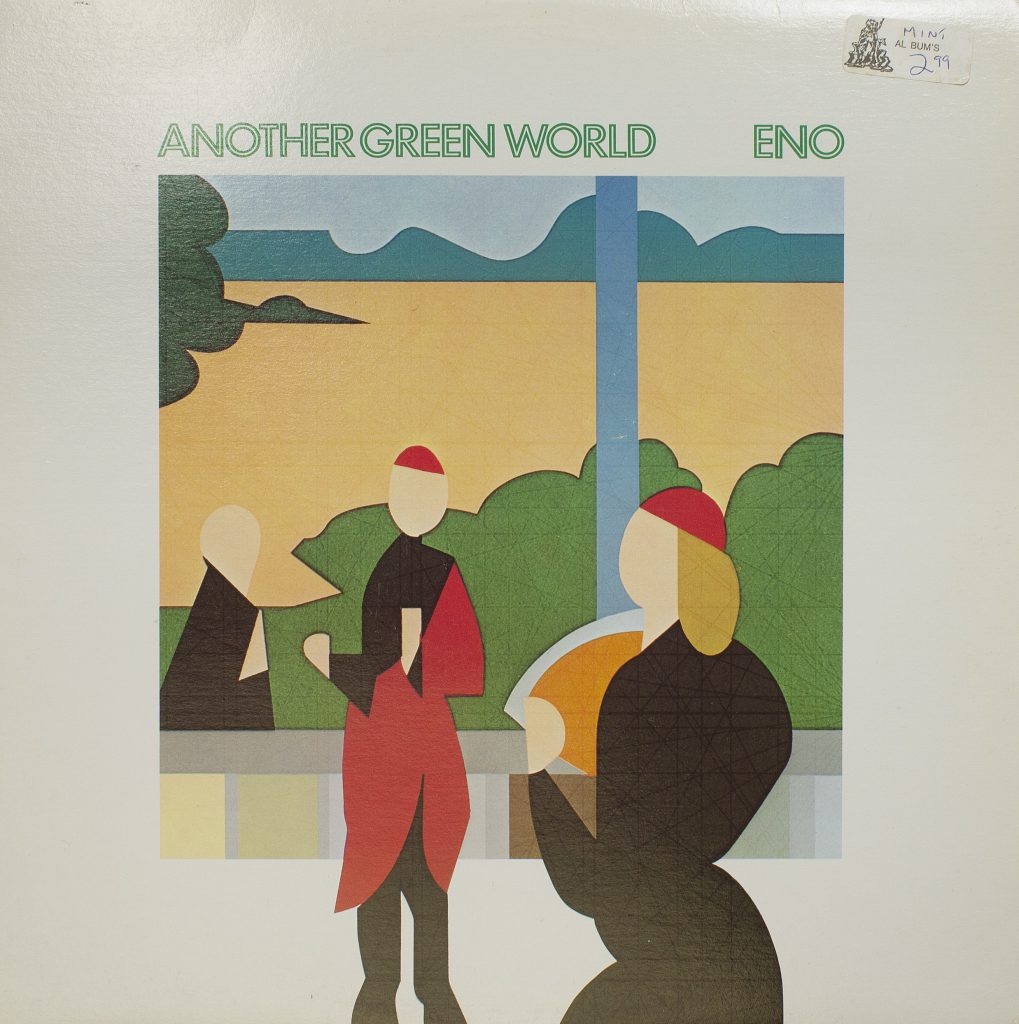

Brian Eno. Another Green World. EG Records, 1975. LP recording, cover from After Raphael by Tom Phillips.

The third solo album by Brian Eno after he left Roxy Music. Parts of Another Green World are explicitly science fiction in content, and the album also marks the moment when Eno first put into action his theories of the recording studio as a musical instrument. Geeta Dayal identifies “innate ambiguity” as a characteristic of this album “crammed with sonic information.”

Science fiction, like rock ’n’ roll, is a form capable of integrating all influences while still remaining unmistakably itself. Rock ’n’ roll, like science fiction, is open to newcomers. the vocabulary can be learned and is an endlessly resilient process of discovery. Both forms are very slippery of definition but are instantly recognizable.

No. 43.

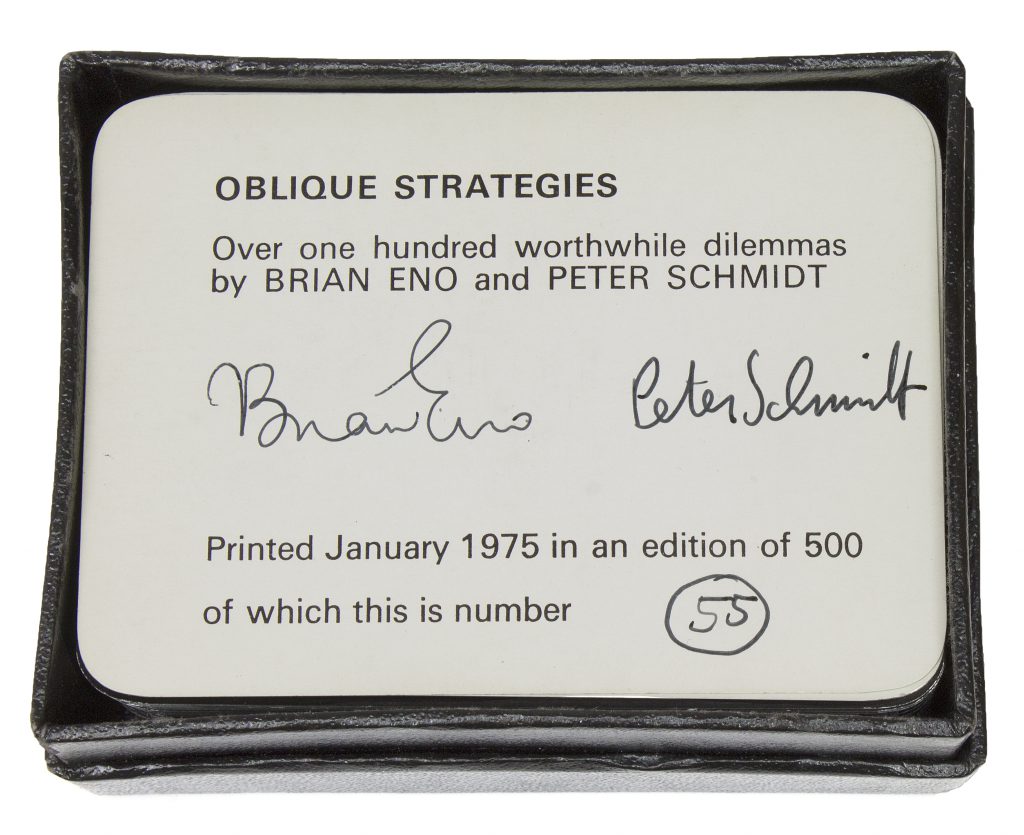

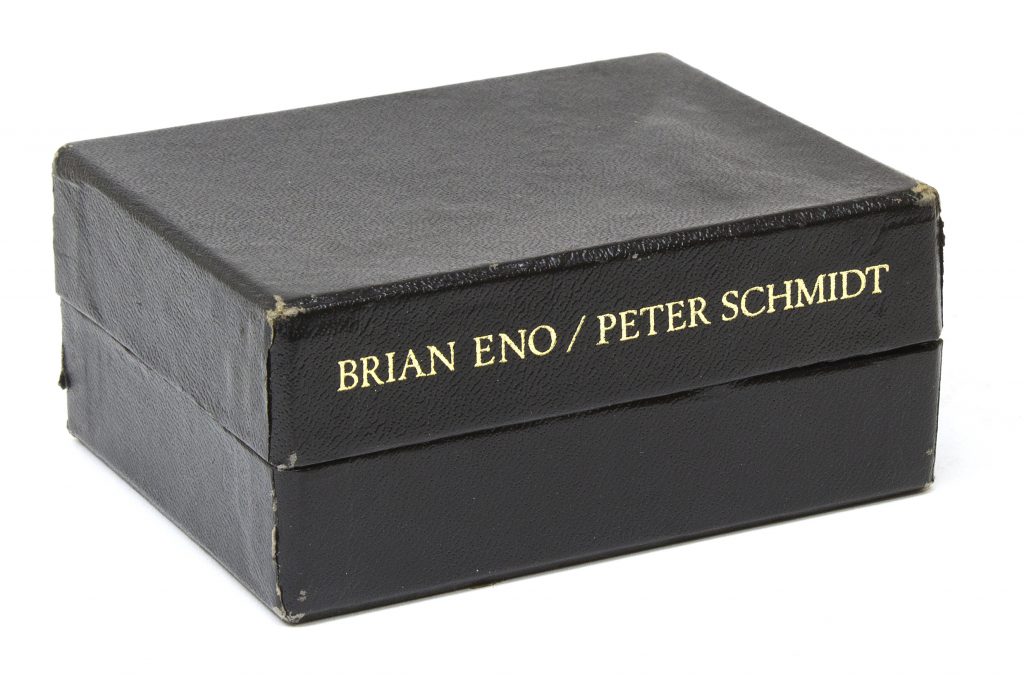

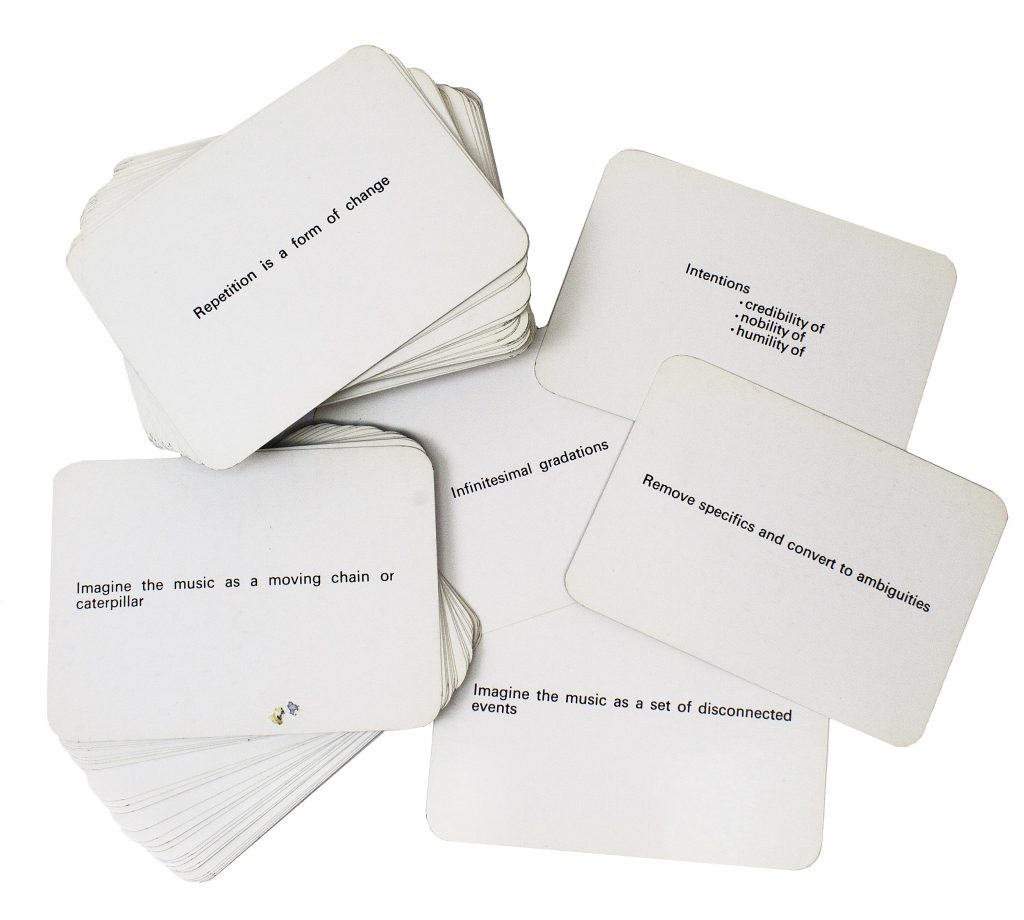

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt. Oblique Strategies. Over one hundred worthwhile dilemmas. London: January 1975.

A deck of instruction cards intended to introduce elements of chance into any creative process. Eno used these during the recording of Another Green World, which often challenged the musicians working with him on Another Green World, but Eno ended up with a masterpiece where synthesizers, electric guitar, and vocals evoke strange landscapes and richly textured narratives.

The first edition, one of 550 copies, signed by Eno and Schmidt. In the original black paper box.

No. 43.

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt. Oblique Strategies. Over one hundred worthwhile dilemmas. London: January 1975.

No. 43.

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt. Oblique Strategies. Over one hundred worthwhile dilemmas. London: January 1975.

In the original black paper box.

No. 43.

Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt. Oblique Strategies. Over one hundred worthwhile dilemmas. London: January 1975.

A deck of instruction cards intended to introduce elements of chance into any creative process. Eno used these during the recording of Another Green World, which often challenged the musicians working with him on Another Green World, but Eno ended up with a masterpiece where synthesizers, electric guitar, and vocals evoke strange landscapes and richly textured narratives.

The first edition, one of 550 copies, signed by Eno and Schmidt. In the original black paper box.

No. 43.

Tom Phillips. “the reader is the artist” [Humument Fragment: Readers]. Watercolor and collage on book page, [ca. 2009].

In 1966, artist Tom Phillips found a second-hand book for threepence and altered every page by painting, collage, and cut-up techniques, to create an entirely new version. The book he found was a Victorian obscurity, A Human Document by W.H. Mallock (1892), and Phillips transformed it into A Humument, first published serially in the 1970s and as a bound book in 1980. A Humument continued to evolve: the sixth or “Final” edition was issued in 2016.

This image was published as the back cover illustration to Tom Phillips’ Readers Vintage People on Photo Postcards (Bodleian Library, 2010).

Brian Eno wrote, “I first met Tom Phillips at Ipswich Art School in 1964. I was a 16-year-old student and he was one of my tutors.” In 1978, Eno produced the opera Irma, adapted by composer Gavin Byars from A Humument.

Alice Sheldon. Ten Thousand Light-Years from Home. By James Tiptree, Jr. With a new Introduction by Gardner Dozois. Boston: Gregg Press, 1976.

Alice Sheldon (1915–87) wrote most of her fiction in the span of a single tumultuous decade in America, 1967–77, under the pseudonym of James Tiptree, Jr. The Tiptree voice expressed an easy competence and clarity and an understanding of the way worlds worked. Tiptree stories are almost invariably about death: beautifully written, sometimes very funny and sometimes very sexy, but inexorable and unflinching.

In 1977, a fan writer revealed Tiptree’s identity. Alice Sheldon wrote to a correspondent, “As to writing, I am dead.”

Inscribed by the author to her editor, “Dave Hartwell with unbounded regard James Tiptree Jr. Alli.”

No. 44.Alice Sheldon. “A Day Like Any Other,” [in:] Foundation 3 (1973).

The first British publication by James Tiptree, Jr., “A Day Like Any Other,” written in 1968, contains, in miniature and hiding in plain sight, all the concerns of its author, Alice Sheldon.

The James Tiptree, Jr., award is given in her memory to work exploring gender roles.

Sheldon’s life was as fantastical as anything Tiptree ever wrote. Julie Phillips’ exemplary biography, James Tiptree, Jr. The Double Life of Alice Sheldon, published in 2006, won the Hugo award.

No. 44.

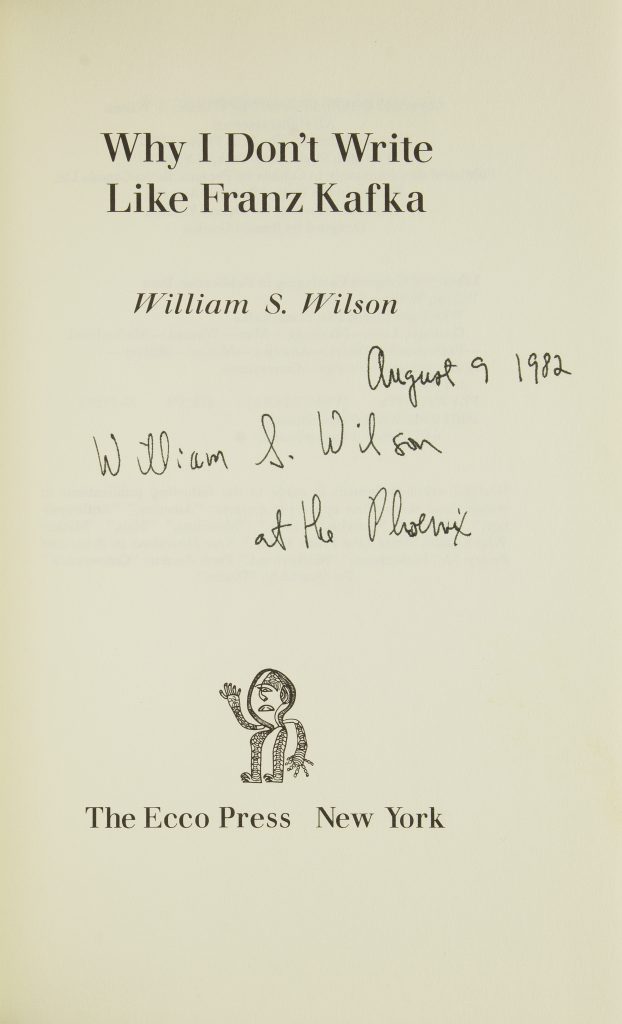

William S. Wilson. Why I Don’t Write Like Franz Kafka. New York: The Ecco Press, [1977].

I met William S. Wilson (1932–2016), interpreter of the work of artist Ray Johnson, during the one semester he taught at Columbia, and we remained lifelong friends. I valued his clear thinking about the import of words, and nowhere is his clarity more apparent than in the stories that comprise Why I Don’t Write Like Franz Kafka. The science in Wilson’s stories is often medical. The vocabulary is almost clinical, but as in J. G. Ballard and Michael Blumlein, Wilson’s is not a sterile jargon but creative and rich in ambiguity: it is language in action.

Signed by the author on the title page, “August 9 1982 William S. Wilson at the Phoenix.”

No. 45.

Robert Sheckley. A Multimedia Album Based on the Complete Text of Robert Sheckley’s In a Land of Clear Colors. Music Brian Eno. Narration Peter Sinfield. Illustration Leonor Quiles. Santa Eulalio del Rio, Ibiza, 1979.

Robert Sheckley (1928–2005) is the master satirist of late twentieth-century science fiction. A prolific short story writer during the 1950s and early 1960s, Sheckley’s humor mocks many of the preoccupations of science fiction: exploration of planets, first contact with aliens, life on board spaceships, and other standard situations and plots from pulp fiction and turned them into something else. In a Land of Clear Colors is humorous tale of interstellar exploration, balancing a comedy of intercultural misunderstandings against a genuinely moving tale of a man who finds the world changing in ways he can never quite grasp This multimedia album features early ambient music by Brian Eno. The album was produced through an art gallery in Ibiza in the Balearic Islands. There must have been some great parties.

No. 46.

Robert Sheckley. A Multimedia Album Based on the Complete Text of Robert Sheckley’s In a Land of Clear Colors. Music Brian Eno. Narration Peter Sinfield. Illustration Leonor Quiles. Santa Eulalio del Rio, Ibiza, 1979.

Robert Sheckley (1928–2005) is the master satirist of late twentieth-century science fiction. A prolific short story writer during the 1950s and early 1960s, Sheckley’s humor mocks many of the preoccupations of science fiction: exploration of planets, first contact with aliens, life on board spaceships, and other standard situations and plots from pulp fiction and turned them into something else. In a Land of Clear Colors is humorous tale of interstellar exploration, balancing a comedy of intercultural misunderstandings against a genuinely moving tale of a man who finds the world changing in ways he can never quite grasp This multimedia album features early ambient music by Brian Eno. The album was produced through an art gallery in Ibiza in the Balearic Islands. There must have been some great parties.

No. 46.

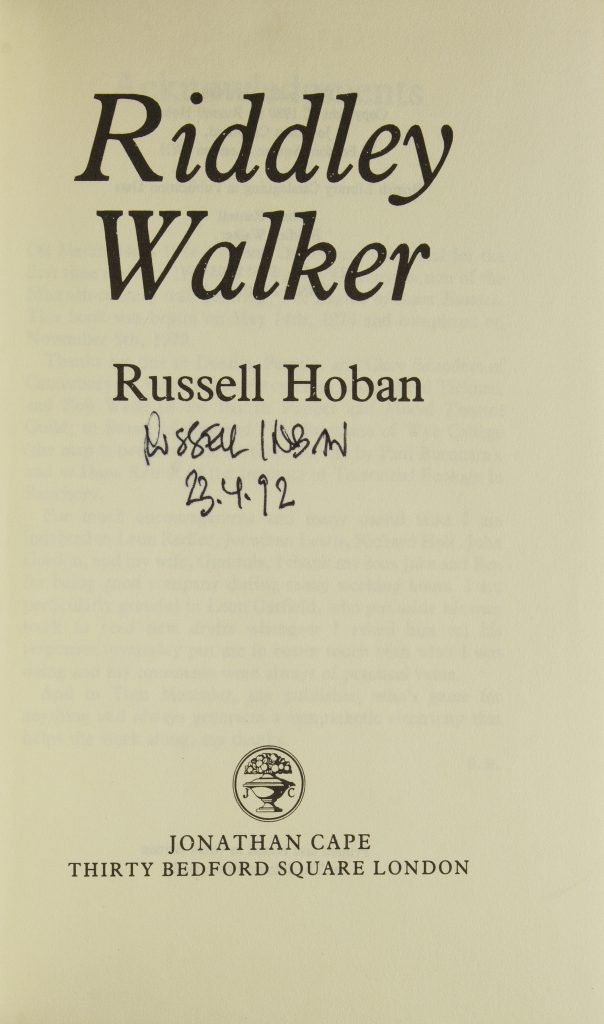

Russell Hoban. Riddley Walker. London: Jonathan Cape, 1980.

Language is the beating heart of Riddley Walker, a novel set in the ruined landscape of Kent long after the end of our civilization. The English that young Riddley Walker speaks is debased and savage but still vital and immediately comprehensible. It encodes secrets vaster than the young man can know: the old oral lore contains the long-lost formula for gunpowder. Echoes of Doctor Mirabilis here, at the other end of time.

No. 48.

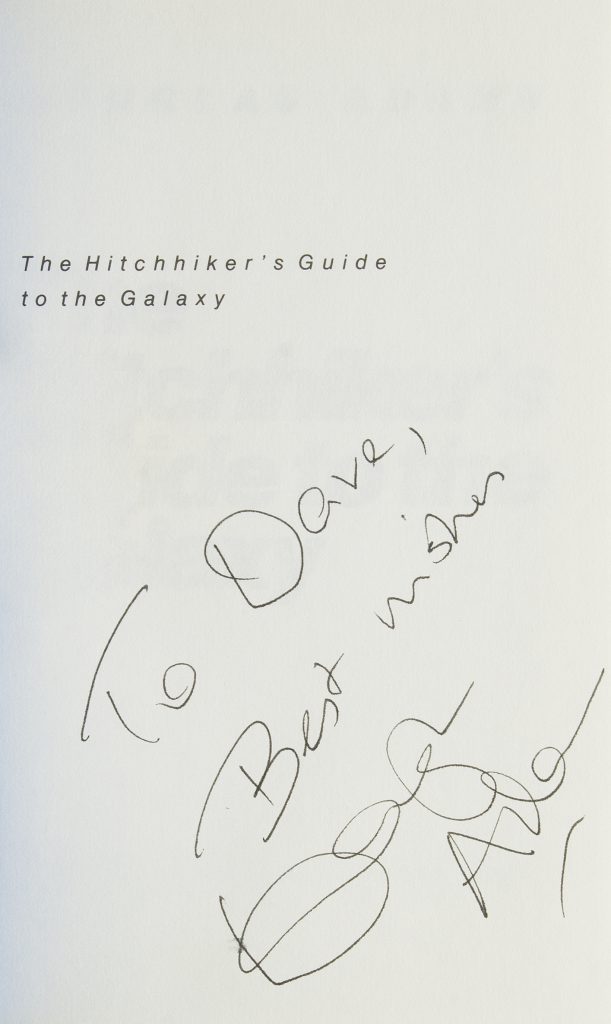

Douglas Adams. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Harmony Books, 1980.

The comic misadventures of gormless Earthling Arthur Dent, as he travels the galaxy with Ford Prefect, a guy “who really knows where his towel is.” Based on on the BBC radio show, this novel mocks the militaristic tendencies and standard characters of pulp science fiction, all of which persist in film.

In many ways, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is the complete opposite of Star Wars — call it Star Peace — and in that respect it is in the line of the British New Wave: a British answer to American dominance. Douglas Adams freely acknowledged the influence of the work of Robert Sheckley.

First American edition, inscribed by the author to David G. Hartwell on the half-title page.

No. 47.

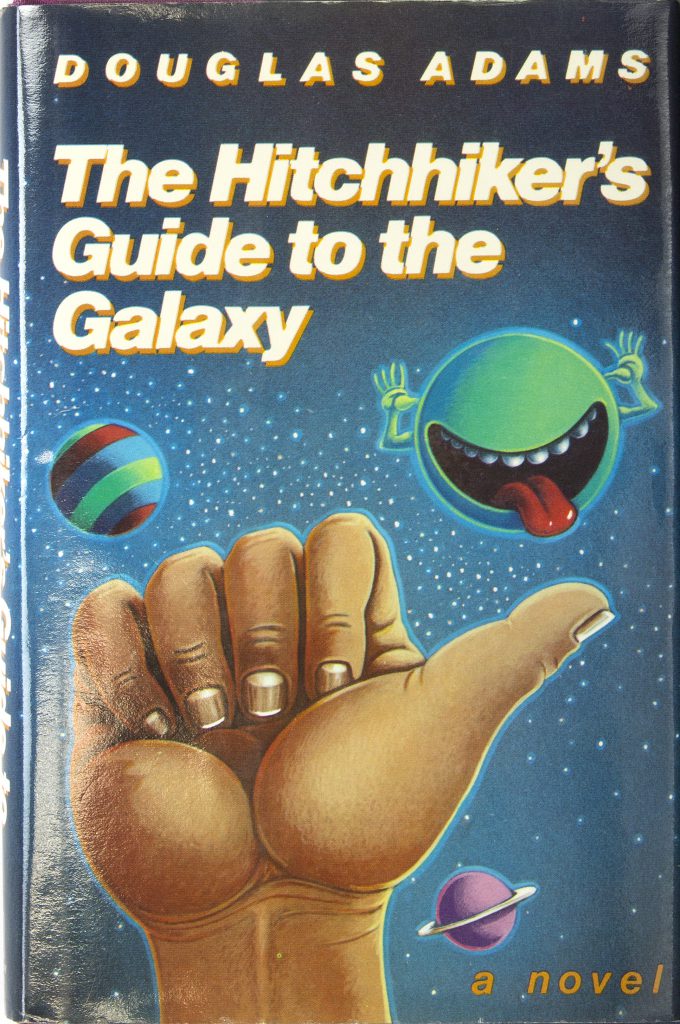

Douglas Adams. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Harmony Books, 1980.

Dust jacket of the first American edition.

No. 47.

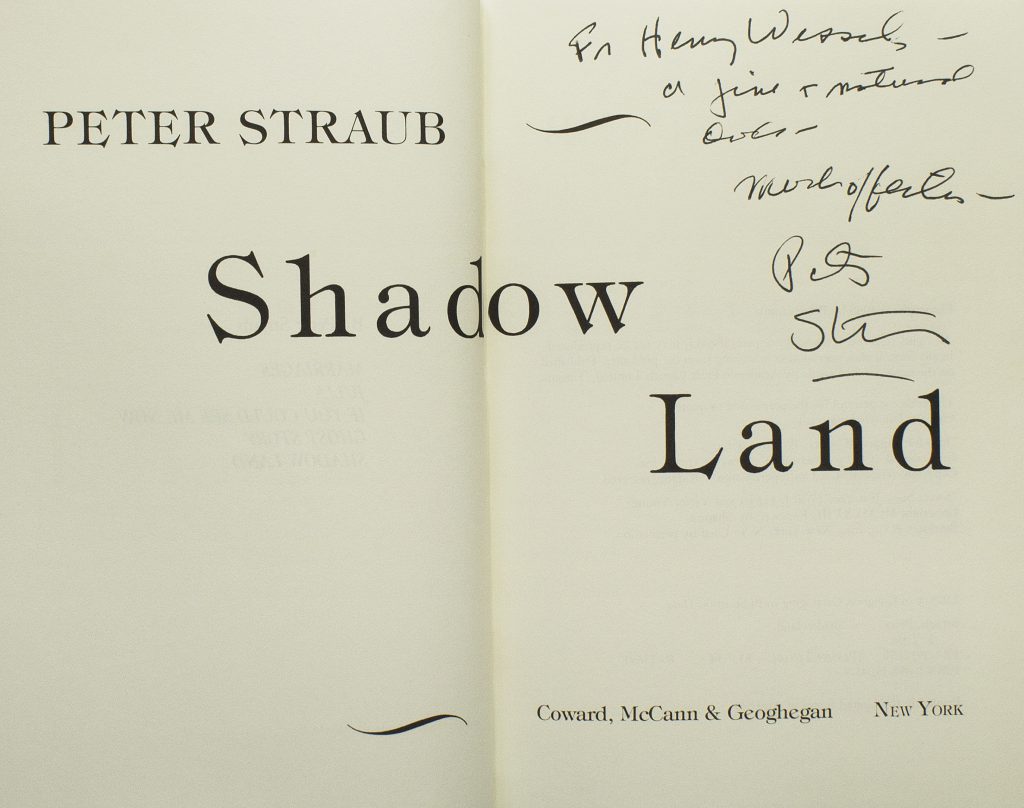

Peter Straub. Shadow Land. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1980.

“To do magic, to do great magic, he has to know himself as a piece of the universe.”

“A piece of the universe?”

“A little piece that has all the rest of it. Everything outside him is also inside him.”

Peter Straub is one of the few magicians I have ever met: that rare real thing, a writer who starts a tale in a recognizable place and enables the reader to go somewhere unexpected and unsettling. Perception is malleable, suggests Straub; memory struggles against silence.

One summer long ago, schoolboys Tom and Del travel to Vermont to spend a summer with Del’s reclusive uncle, Coleman Collins, once a legendary magician and performer in England and on the Continent.

No. 49.

Contents

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed