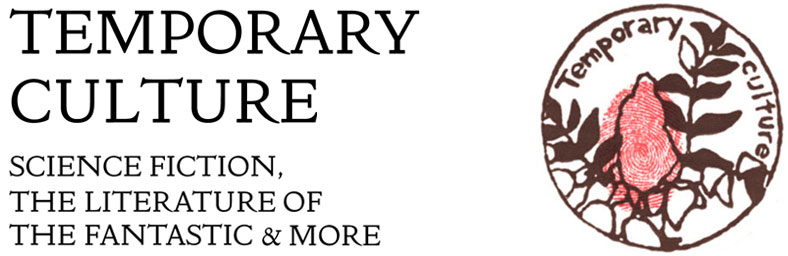

Mary Shelley. The Last Man. By the Author of Frankenstein. London: Henry Colburn, 1826.

The Last Man is the first secular apocalypse and is Mary Shelley’s other important contribution to science fiction. The Last Man is a tale of republican Britain at the end of the twenty-first century, when a plague from Asia spreads across Europe and kills all humans, except for the narrator, Lionel Verney. Mary Shelley began writing the novel in 1824 after she learned of the death of Lord Byron, and The Last Man is notable for its idealized portraits of P. B. Shelley and Byron “in the bright days of his youth.”

No. 4.

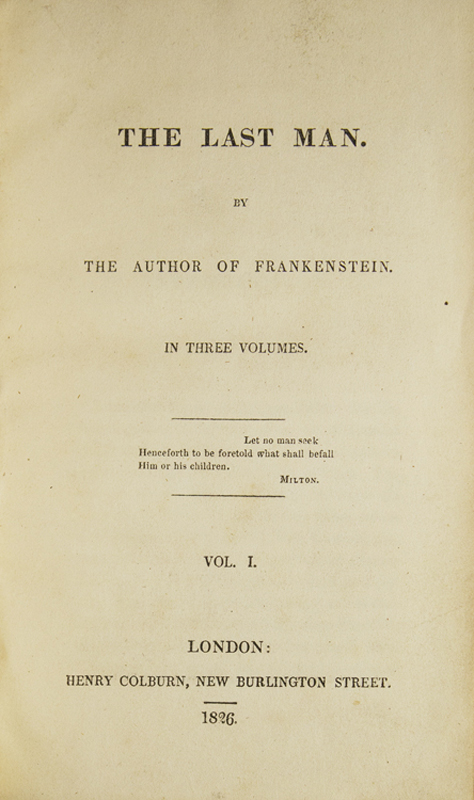

Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. By Mary W. Shelly, Author of ‘The Last Man,’ ‘Perkin Warbeck,’ &c. 2 vols., Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard, 1833. First American edition.

The origins of Frankenstein are well known. In the summer of 1816, Mary Shelley, a brilliant teenager, began her novel of a medical student who creates an artificial human being and endows him with life. Victor Frankenstein is frightened by the “daemon” he has created. The monster learns to read and speak, and confronts his maker, who rejects him. The monster pursues Frankenstein across Europe, leaving a trail of death, and chases Victor into the Arctic. With the stage production of Presumption! Or, the Fate of Frankenstein in 1823, Frankenstein’s monster stepped from the pages of Mary Shelley’s book into the world’s imagination.

No. 5.

Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. By Mary W. Shelly, Author of ‘The Last Man,’ ‘Perkin Warbeck,’ &c. 2 vols., Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard, 1833. First American edition.

Volume II is open to p. 25, where the monster speaks his first words, “Pardon this intrusion.”

No. 5.

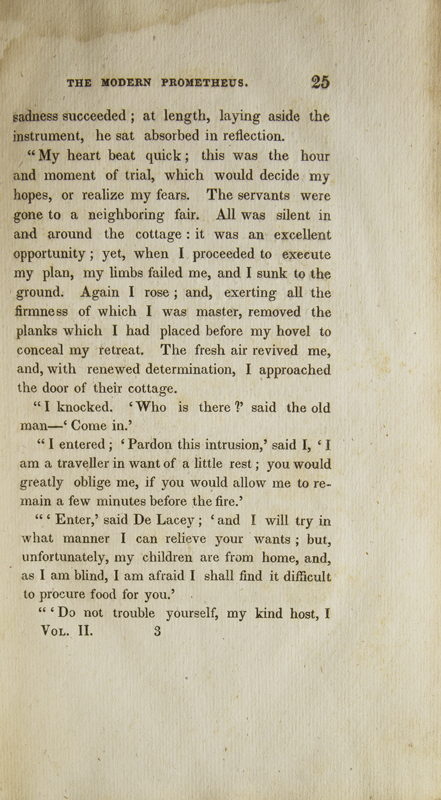

Sara Coleridge. Phantasmion. London: William Pickering, 1837. One of 250 copies.

The first English fantasy novel set entirely in a secondary world. Sara Coleridge was the daughter of the poet S. T. Coleridge (and later editor of his work). She first told this story to her young son and wrote it during a period of ill-health compounded perhaps by her growing addiction to opium.

No. 6

Stella Benson. Living Alone. London: Macmillan, 1920.

The intrusion of a witch into the drudgery of London life during wartime. Benson’s witch moves easily between Hyde Park and Faery, which can also be reached by an easy commuter train from London. The House of Living Alone is a magical store and boarding house, and throughout the novel Benson mocks polite society and those who have forgotten that magic exists.

First published in 1919.

No. 16.

Stella Benson. Living Alone. London: Macmillan, 1920.

Second printing (originally published 1919).

With the ownership signature of Peggy Guggenheim, 1920, on flyleaf.

No. 16.

Hope Mirrlees. Lud-in-the-Mist. London: W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., [1926].

Lud-in-the Mist is a beautifully written tale of the rediscovery of magic. Hope Mirrlees (1887-1978) plays with the conceits of the fairy story, but has created her own fully imagined world. As Michael Swanwick observes, Lud-in-the-Mist “is a dissident work, written in full awareness of what the proper literary writers were up to, and in its refusal to go along with them daringly defiant.”

One of the great fantasy novels of the interwar period, the book was reprinted in the 1970s and influenced new generations of writers, including Joanna Russ, Neil Gaiman, Elizabeth Hand, and many others.

No. 18.

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman. London: Chatto & Windus, 1926.

Lolly Willowes is a chronicle of the power of refusal. As a dependent in her brother’s house, Laura “Lolly” Willowes finds her world constricted. “She actually had a sensation that she was stitching herself into a piece of embroidery with a good deal of background.” She takes lodgings in the Shropshire village of Great Mop, and after a midnight country dance, she meets the devil in a small, empty field.

No. 19.

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman. London: Chatto & Windus, 1926.

With an autograph quotation, signed: “Sylvia Townsend Warner ‘Laura hated ink’ p. 210”.

No. 19.

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman. London: Chatto & Windus, 1926.

Another copy, in original printed dust jacket.

No. 19.

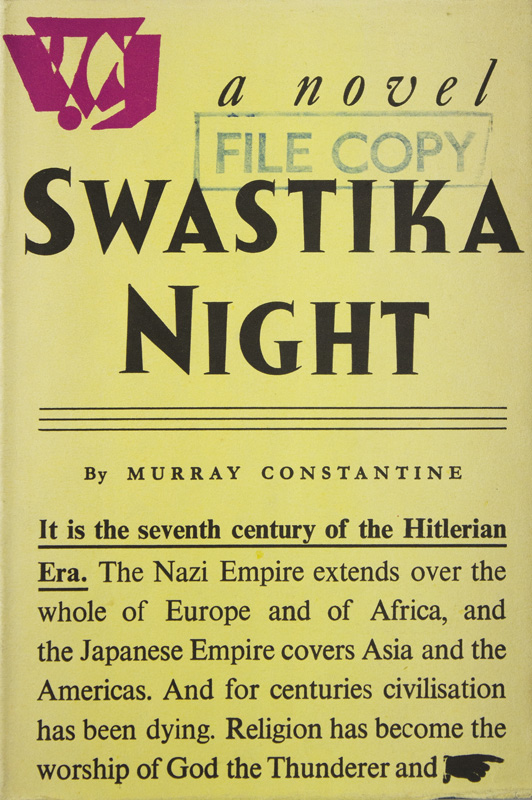

Katharine Burdekin. Swastika Night by Murray Constantine. London: Gollancz, 1937.

Swastika Night is a landmark feminist science fiction novel, set seven hundred years after a Nazi conquest of Europe, where Hitler is worshipped as an Aryan god, all written evidence of the past has been eradicated, and the Jews have been exterminated. Women are kept only as breeding animals, and are deemed to be without souls or intellectual capacity. Some science fiction authors wrote with clarity and prescience about the state of the world in the late 1930s.

The novel was published under a pseudonym, and only in the 1980s did scholar Daphne Patai identify the author as Katharine Burdekin (1896-1963).

The Gollancz file copy, in the rare dust jacket.

No. 26.

Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. Introduction by Francis Wyndham. London: Andre Deutsch, 1966.

I include Wide Sargasso Sea in the literatures of the fantastic because it is, quite simply, a pioneering work. What Rhys accomplishes is a perfect example of the critical fiction: a writer’s artistic response to another work of literature. This short novel of the life of a Creole heiress to lands in Jamaica and Dominica is an indictment of a legal system that assigns a wife’s money and properties to the fortune-hunting husband; it is also the story of the first Mrs. Rochester of Jane Eyre.

No. 35.

Jean Rhys. Wide Sargasso Sea. Introduction by Francis Wyndham. London: Andre Deutsch, 1966.

Title page of the first edition.

No. 35.

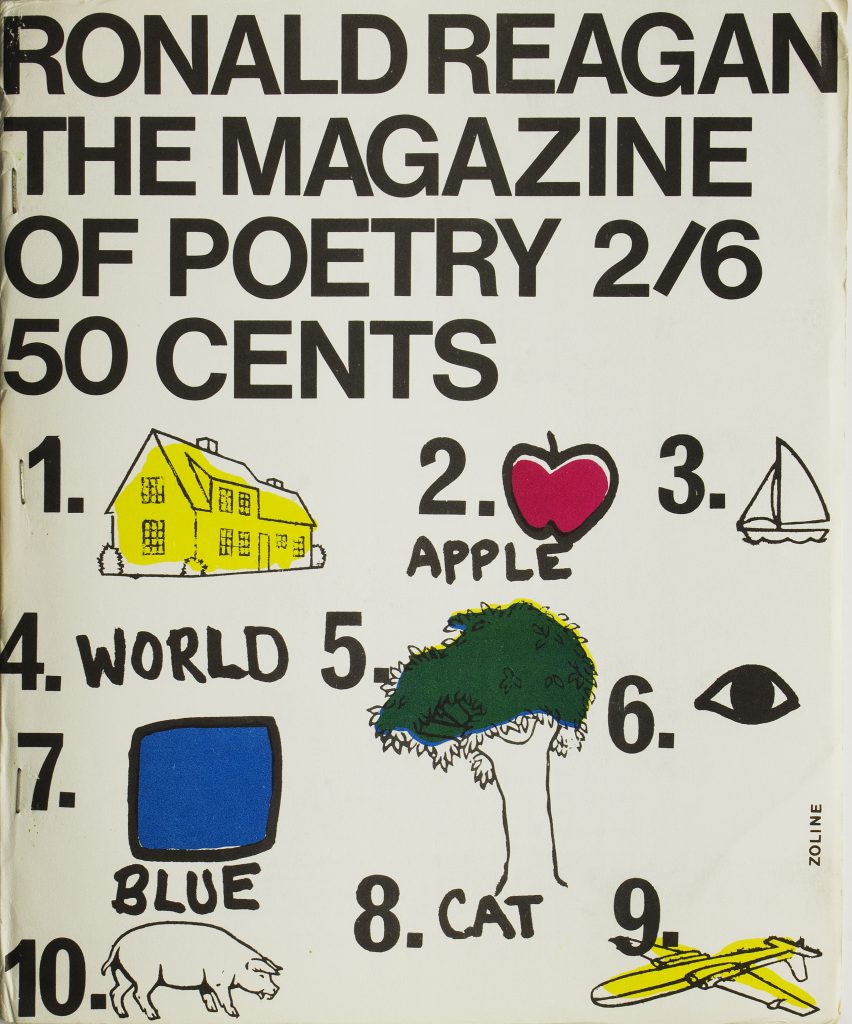

John Sladek, Pamela Zoline, and Thomas M. Disch. Ronald Reagan The Magazine of Poetry. London, 1968.

John Sladek, satirist, laughing fatalist, and “the high priest of something else,” and his flatmates published this poetry, protest, and science fiction ’zine at the intersection of the Anglo-American literary avant-gardes, the New York East Village scene and British New Wave. The magazine includes J. G. Ballard’s obscene satire on Ronald Reagan, then serving as governor of California.

Pictorial wrappers by Sladek and Zoline. Provenance: Thomas M. Disch, contributing editor.

No. 38.

John Sladek, Pamela Zoline, and Thomas M. Disch. Ronald Reagan The Magazine of Poetry. London, 1968.

Pictorial wrappers by Sladek and Zoline.

No. 38.

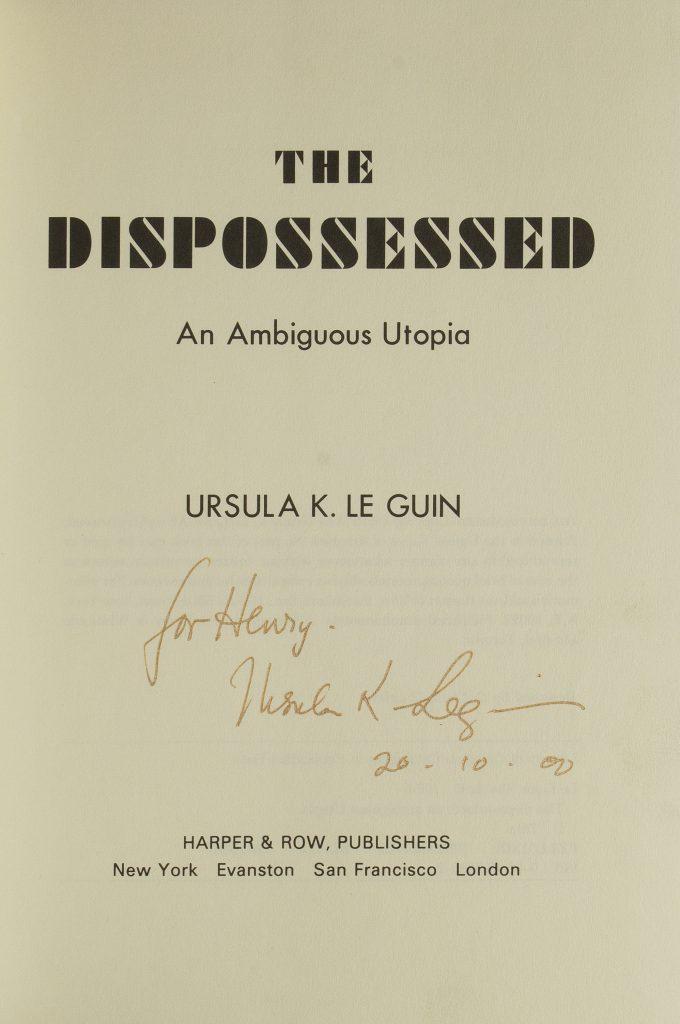

Ursula K. Le Guin. The Dispossessed. An Ambiguous Utopia. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Le Guin’s novel of a moon and its planet: the stark, almost desert-like world of the moon Annares, an anarchist cooperative society, and the much larger capitalist world of Urras. The book starts simply. “There was a wall. It did not look important.” Shevek, mathematician of Annares, arrives in Urras with nothing but his ideas, which are revolutionary. The Dispossessed won the Hugo and Nebula awards.

No. 42.

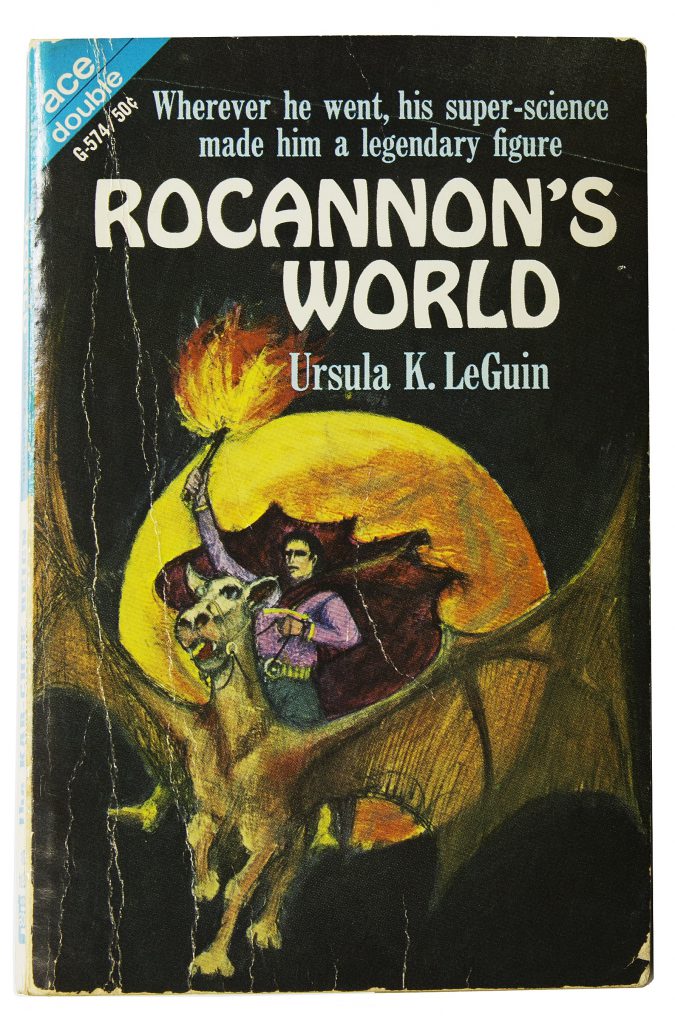

Ursula K. Le Guin. Rocannon’s World. New York: Ace Books, 1966. Ace Double G-574. Bound with: Avram Davidson. The Kar-Chee Reign.

Ursula K. Le Guin (born 1929) wrote extensively during the 1950s, but she found her way into print when Cele Goldsmith, editor of Amazing Stories and Fantastic magazines from 1958 to 1965, bought her fantastical stories. Le Guin expanded “The Dowry of Angyar” (1964) into Rocannon’s World, her first book, published as an Ace Double paperback original.

No. 42.

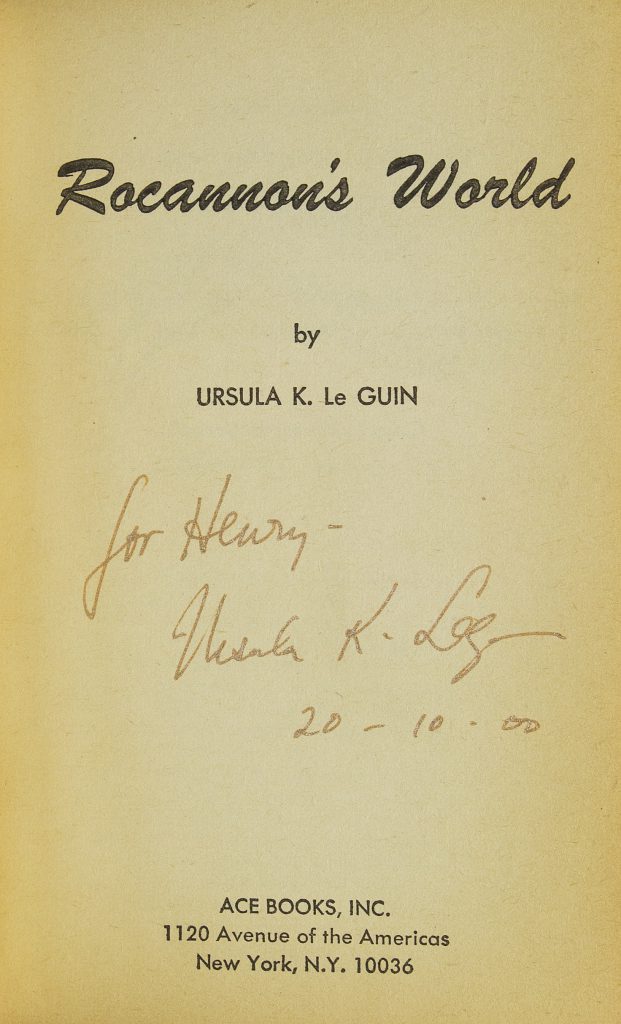

Ursula K. Le Guin. Rocannon’s World. New York: Ace Books, 1966. Ace Double G-574. Bound with: Avram Davidson. The Kar-Chee Reign.

Inscribed by the author on the title page.

No. 42.

Alice Sheldon. Ten Thousand Light-Years from Home. By James Tiptree, Jr. With a new Introduction by Gardner Dozois. Boston: Gregg Press, 1976.

Alice Sheldon (1915–87) wrote most of her fiction in the span of a single tumultuous decade in America, 1967–77, under the pseudonym of James Tiptree, Jr. The Tiptree voice expressed an easy competence and clarity and an understanding of the way worlds worked. Tiptree stories are almost invariably about death: beautifully written, sometimes very funny and sometimes very sexy, but inexorable and unflinching.

In 1977, a fan writer revealed Tiptree’s identity. Alice Sheldon wrote to a correspondent, “As to writing, I am dead.”

Inscribed by the author to her editor, “Dave Hartwell with unbounded regard James Tiptree Jr. Alli.”

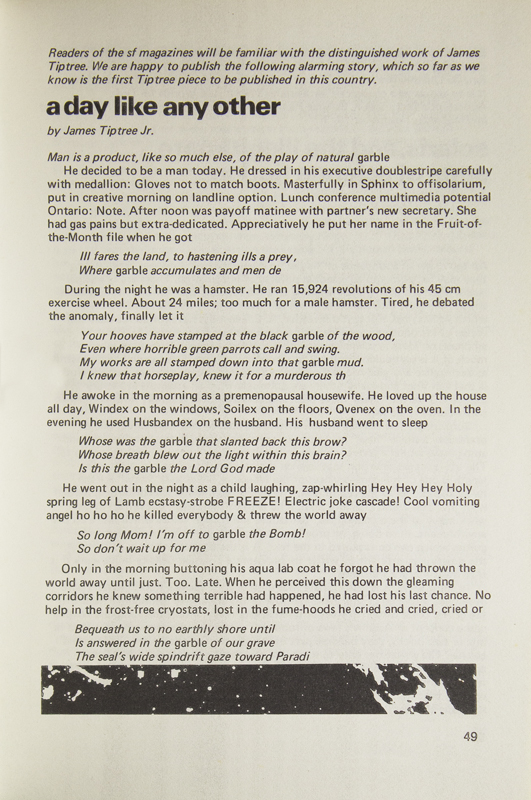

No. 44.Alice Sheldon. “A Day Like Any Other,” [in:] Foundation 3 (1973).

The first British publication by James Tiptree, Jr., “A Day Like Any Other,” written in 1968, contains, in miniature and hiding in plain sight, all the concerns of its author, Alice Sheldon.

The James Tiptree, Jr., award is given in her memory to work exploring gender roles.

Sheldon’s life was as fantastical as anything Tiptree ever wrote. Julie Phillips’ exemplary biography, James Tiptree, Jr. The Double Life of Alice Sheldon, published in 2006, won the Hugo award.

No. 44.

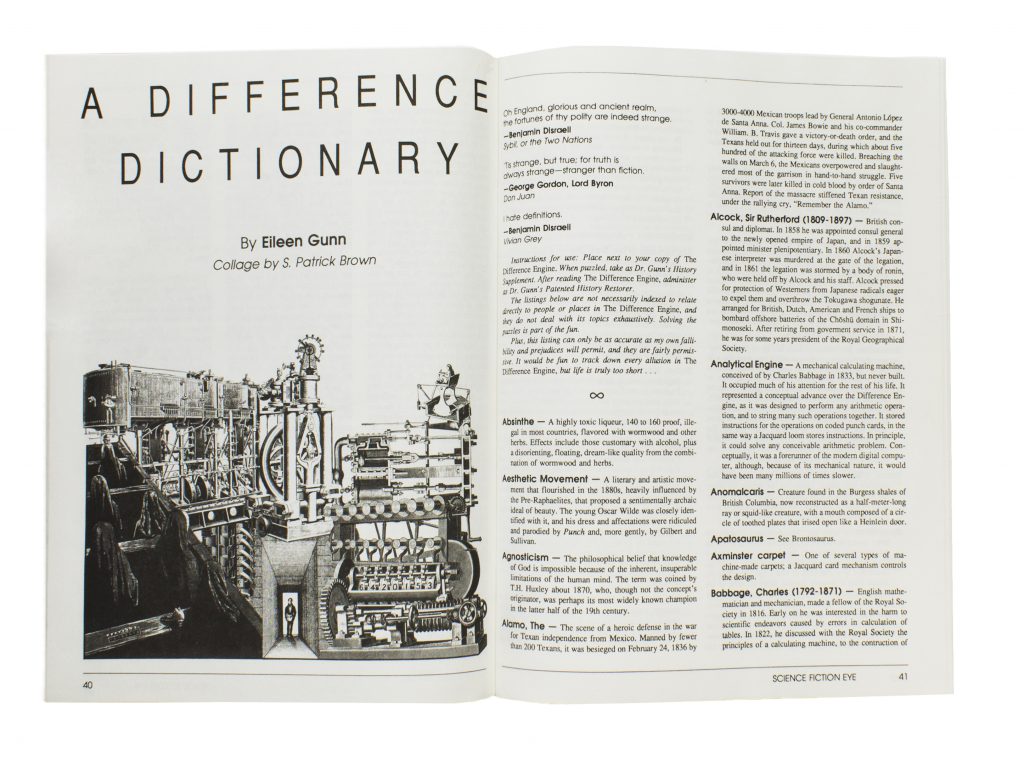

Eileen Gunn. “A Difference Dictionary,” [in:] Science Fiction Eye 8, Winter 1991.

Eileen Gunn’s gloss on Gibson and Sterling’s The Difference Engine, in an issue of the smart and stylish critical magazine Science Fiction Eye.

No. 54.

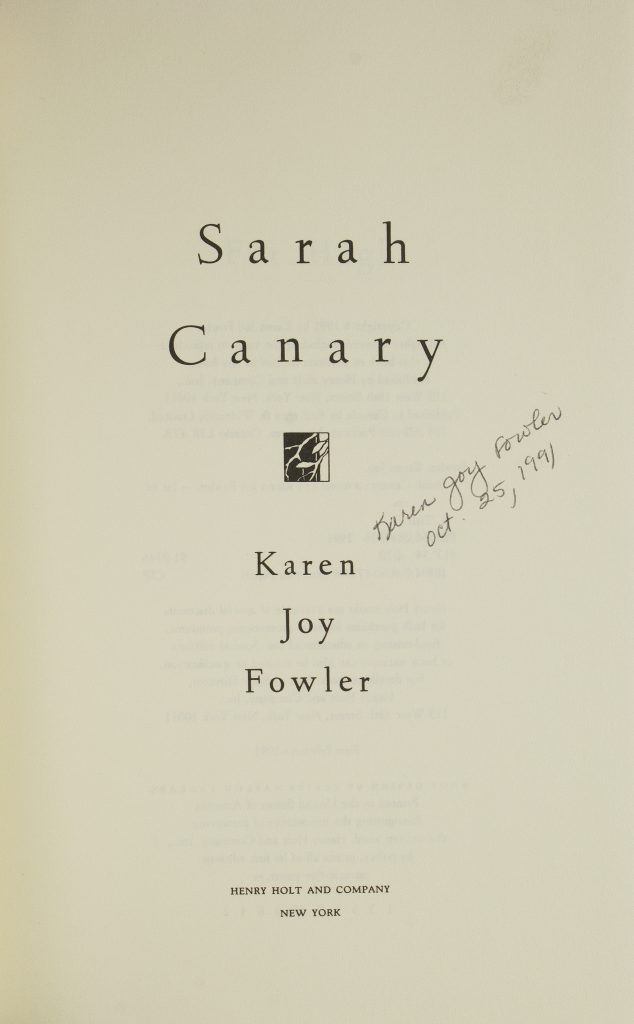

Karen Joy Fowler. Sarah Canary. New York: Henry Holt, 1991

Sarah Canary is a first contact tale set in late nineteenth-century America. A strange, badly dressed white woman, with “skin poreless and polished,” shining like porcelain, appears near an itinerant railway workers’ camp in the woods of Washington. No one, not even a polyglot Chinese man, can understand her speech. She is confined to an asylum. “As an emblem of the enigma behind the idea of first contact she is perhaps definitive. As a dramatization of the self-deluding imperialisms of knowledge, Sarah Canary is equally convincing” (SFE). Fowler is also author of The Jane Austen Book Club (2004).

No. 55.

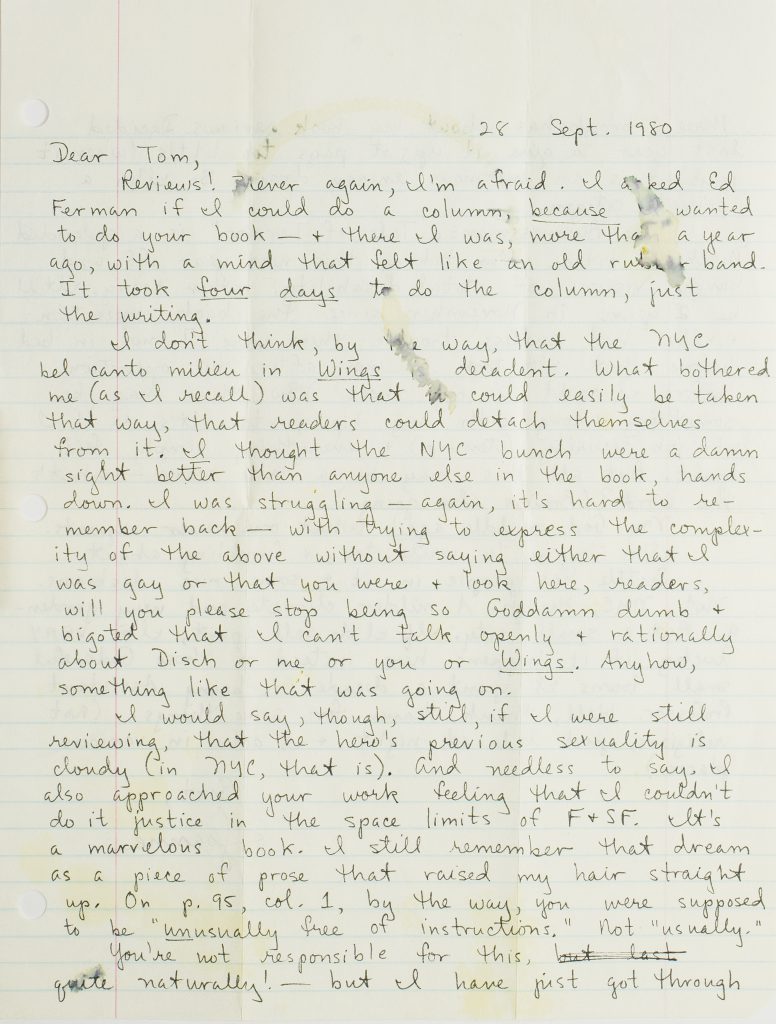

Joanna Russ. Autograph Letter, signed, to Thomas M. Disch, 28 September 1980.

Joanna Russ (1937–2011) is the rainy night sky when the whole box of fireworks goes up at once, a blazing angel saying, Look! She was one of the fiercest intellects in science fiction in the 1960s and 1970s, a writer of excellent short fiction and one of the best critics of contemporary work and earlier authors. Ill health largely curtailed her fiction and critical writing after the early 1980s.

She writes her friend Tom Disch, whose novel On Wings of Song (1979) she had just reviewed: “Reviews! Never again, I’m afraid.”

No. 61.

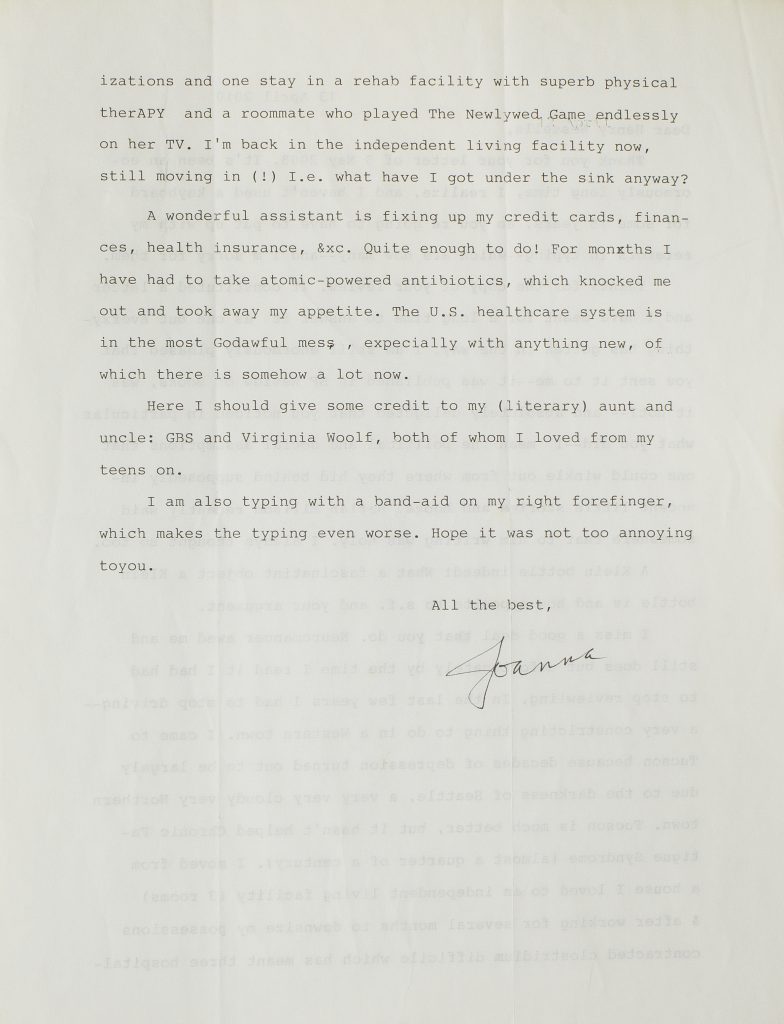

Joanna Russ. Typed Letter, signed, to Henry Wessells, 13 April 2010.

“What a fascinating object a Klein bottle is and how apposite to s.f. and your argument. [. . .] Neuromancer awed me and still does but unfortunately by the time I read it I had to stop reviewing.”

No. 61.

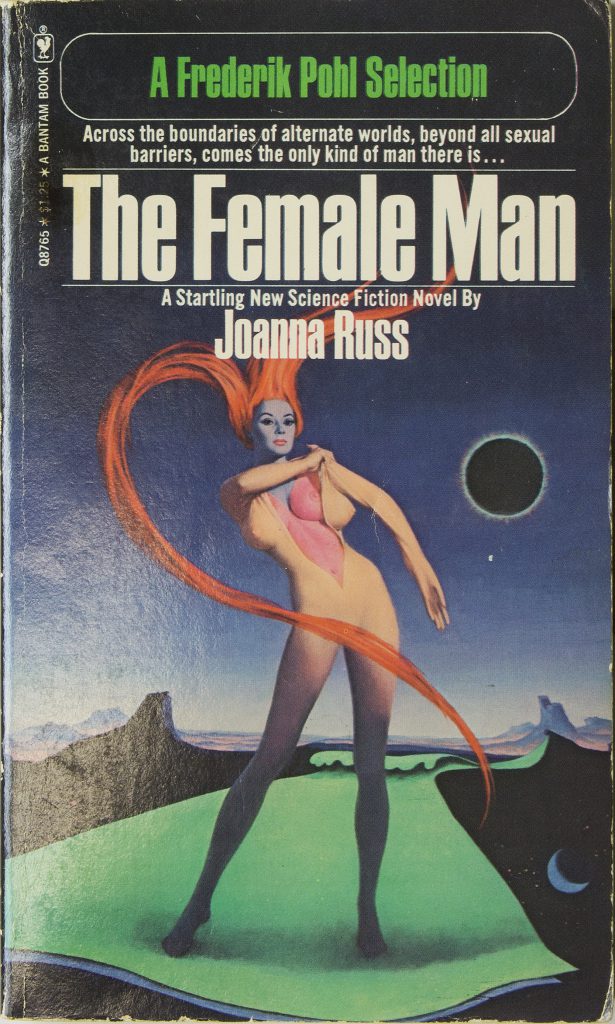

Joanna Russ. The Female Man. New York: Bantam Books, 1975.

“In 1975 Russ published The Female Man, which must be accounted the best feminist science-fiction novel of all time [. . .] Russ wants to empower women.”

— Thomas M. Disch

A novel of life on the women’s planet Whileaway, in the form of four linked stories in which alternate versions of the protagonist move from servility to liberation.

No. 61.

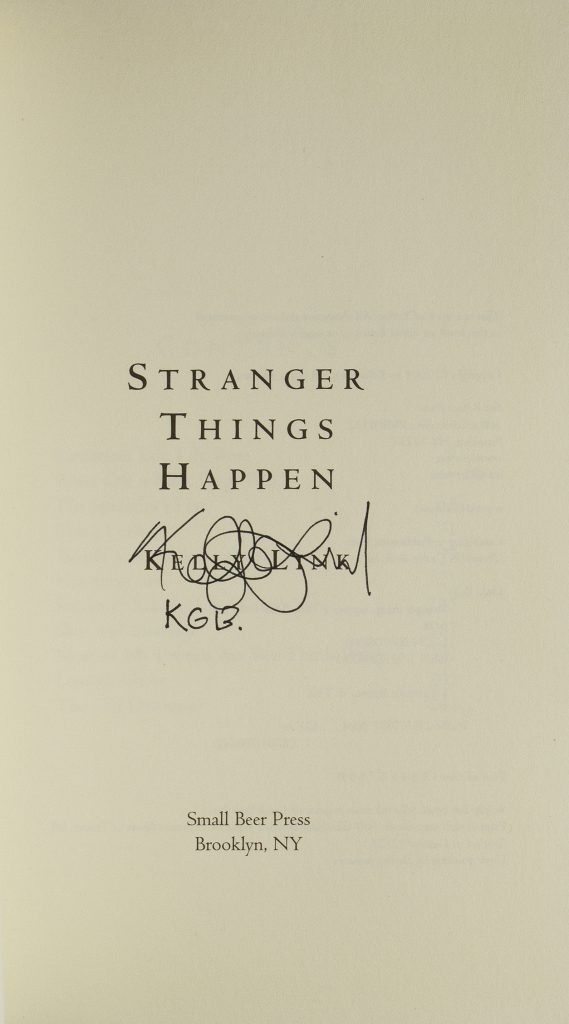

Kelly Link. Stranger Things Happen. Brooklyn, NY: Small Beer Press, 2001.

First book by the critically acclaimed Kelly Link, whose short fiction has won the Hugo, Nebula, Tiptree, and World Fantasy awards.

Also the first book from Small Beer Press, who have gone on to publish many notable award-winning books from established authors as well as by new writers.

No. 64.

Susanna Clarke. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. New York: Bloomsbury, 2004.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell invokes magic in Britain during the Napoleonic Wars, but it is an English magical tradition which Clarke has invented that confers power upon its practitioners. Like Lord Byron, the magician Jonathan Strange derives his power from the manipulation of words. The tradition seems to fit into the known historical and literary and social fabric of our world. This closeness is by turn whimsical and deadly serious, and it is deceptive, for Clarke’s novel constitutes an extension of the geography of imagined lands. The house of Lost-hope, and its doleful corridors, and the fact “that Piccadilly stood in close proximity to a magical wood,” are potent additions to the gazetteer of fantasy. Books are integral to Clarke’s tale.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell won the Hugo and World Fantasy awards.

No. 66.

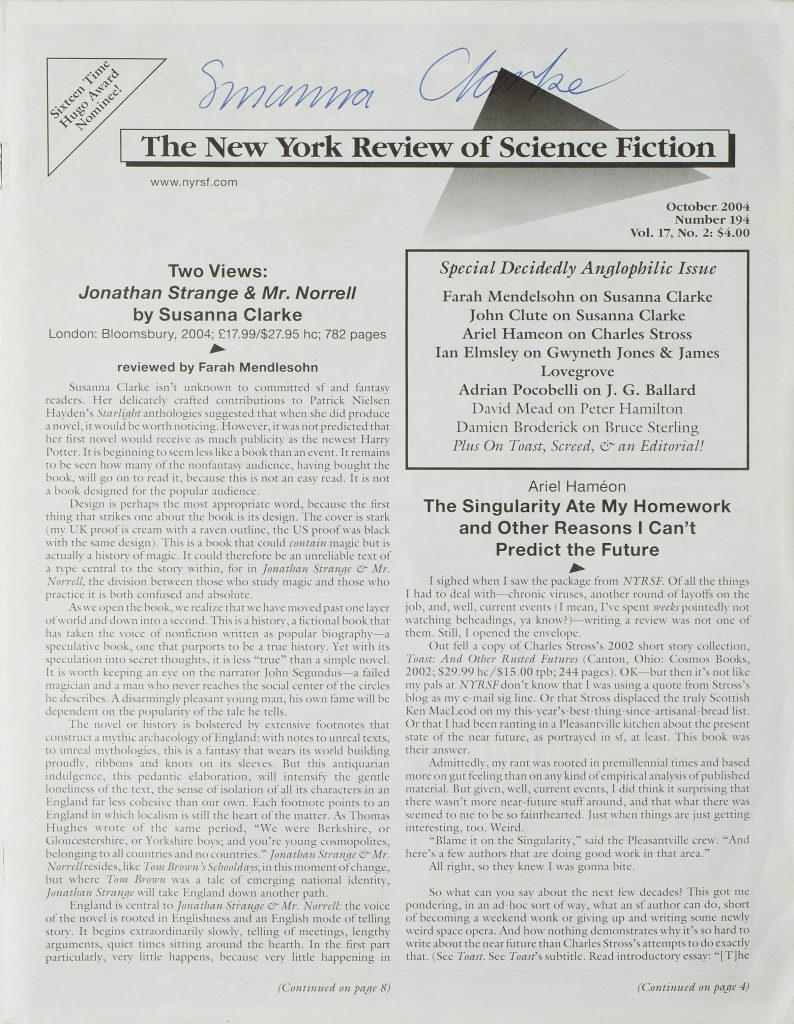

The New York Review of Science Fiction. Special Decidedly Anglophilic Issue. Vol. 17, No. 2. October, 2004.

Signed by Susanna Clarke across the top.

With reviews of Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Farah Mendlesohn and John Clute.

No. 66.

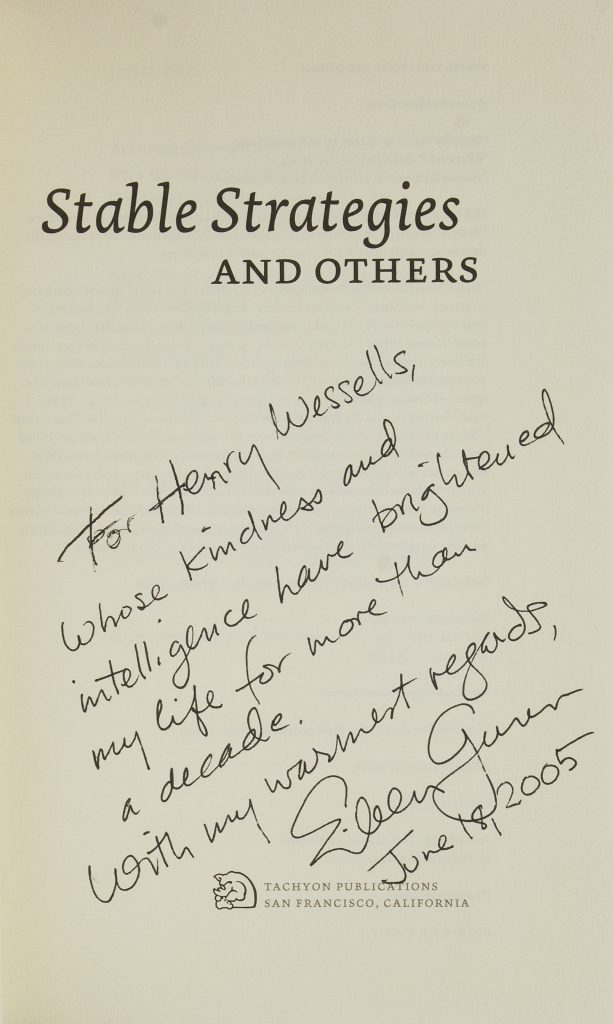

Eileen Gunn. Stable Strategies and Others. San Francisco: Tachyon, 2004.

“It doesn’t follow the old rules.”

Stable Strategies and Others, from San Francisco publisher Tachyon, is a collection assembling stories of corporate and social life in the age of the computer and mass media. Gunn was a director of the advertising department of Microsoft in the mid-1980s, and “Stable Strategies for Middle Management” (1988) is a satire of an office culture where bioengineering modifications are the stepping-stone to success. Other tales look at teen culture, childhood education, and Richard Nixon as a television talk show host. Gunn has a vast acquaintance in science fiction, and several of her stories have been collaborations with other writers in the field. Her website The Infinite Matrix (2001–8) was a brilliant literary science fiction magazine in online form.

No. 67

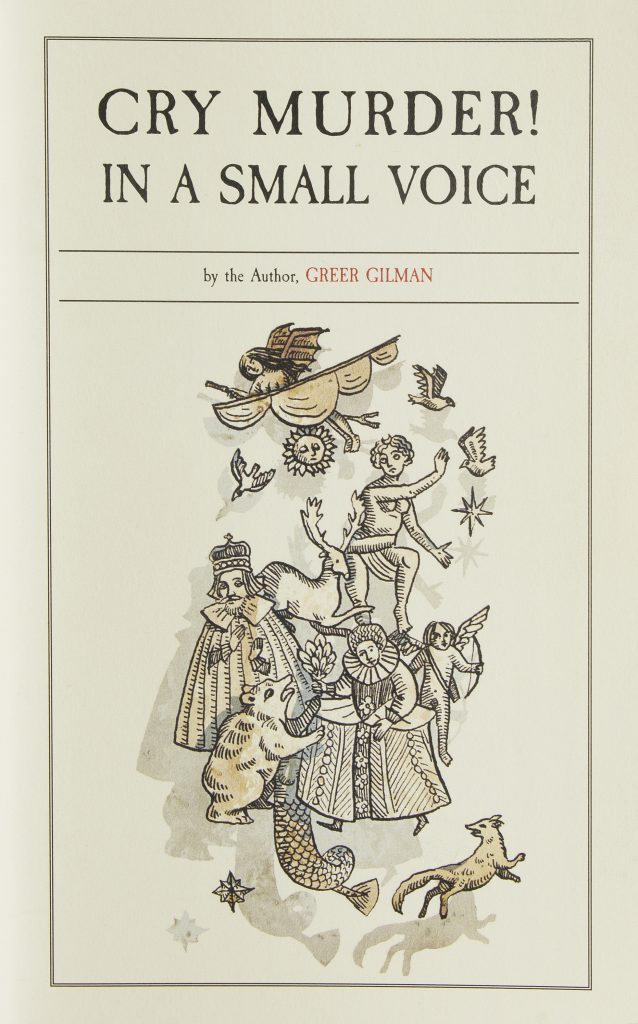

Greer Gilman. Cry Murder! in a small voice. Easthampton, Mass.: Small Beer Press, 2013.

Greer Gilman’s brilliant use of language and her deep knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean stage inform this tale, where poet Ben Jonson investigates the murders of young boys at the ragged edges of the theater. Gilman’s portrait of the criminal is also a razor-sharp dismissal of the theory that the Earl of Oxford wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

Winner of the Shirley Jackson award.

No. 69.

Contents

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed