Thomas Leland. Longsword, Earl of Salisbury. An Historical Romance. Dublin: printed for G. Faulkner, in Essex-Street, 1762.

The first Gothic novel, published before the literary mode even had a name. Here, fully formed at the outset, are most of the tropes of the Gothic literature that enchanted European readers: evil monks, menaced maidens, imprisonment in castles and monasteries, infant kidnappings, “secret malignity,” poisons, and wild coincidences. the gothic sensibility is a re-appropriation of history, seeing the past through new lenses. For the next half a century, writers produced variations on these themes, sometimes with ingenuity and sometimes simply in imitation of earlier authors. Longsword makes no use of the supernatural, but it must also be classed as the first work of horror literature: the torments that the countess Ela suffers are at the hands of monsters in human form.

No. 1.

Le Nagzag, ou Les Mémoires de Christophe Rustaut, dit L’Africain. Amsterdam, et se trouve à Paris: chez J. P. Costard, 1771.

An interesting variation on the imaginary voyage. Shipwrecked on an island off the coast of Sofala in southeast Africa, the narrator sees a footprint is on a deserted beach. One might think of Robinson Crusoe, but Le Nagzag moves into new terrain. Christophe and his companions are welcomed by an old couple in vigorous health. They eat a green leafy herb with extraordinary medicinal and nutritional qualities. The herb, nagzag, produces an intensely stimulating warmth and excites sexual desire in men and women alike. All live together without jealousy, and the properties of nagzag and the country’s history are told in a series of nested narratives. The castaways build a ship to return to the Cape of Good Hope, but it sinks off shore with the loss of the cargo of nagzag leaf and seed. Nagzag is one of the first imaginary drugs in post-classical literature. The work has not yet been translated into English.

No. 2.

Charles Robert Maturin. Melmoth the Wanderer: A Tale. By the Author of “Bertram,” &c. Edinburgh: Printed for Archibald Constable and Company, and Hurst, Robinson, and Co. Cheapside, London, 1820.

Maturin’s late Gothic masterpiece, Melmoth the Wanderer, is a labyrinth sprawling across time and geography and through the ruins of all three Gothic forms: sentimental, historical, and supernatural. Melmoth, a contemporary of John Dee, made a Faustian bargain to gain supernatural powers and prolong his life, and the bargain is coming due. Balzac praised Melmoth, and Baudelaire esteemed “ce pâle et ennuyé Melmoth” as one of the great literary creations. Oscar Wilde was a great-nephew of Maturin, and the portrait in the Melmoth house seems a clear ancestor to Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). Robert Ross wrote a biographical notice of Maturin in the 1892 edition of Melmoth. Wilde adopted the name Melmoth in his final exile.

No. 3.

Mary Shelley. The Last Man. By the Author of Frankenstein. London: Henry Colburn, 1826.

The Last Man is the first secular apocalypse and is Mary Shelley’s other important contribution to science fiction. The Last Man is a tale of republican Britain at the end of the twenty-first century, when a plague from Asia spreads across Europe and kills all humans, except for the narrator, Lionel Verney. Mary Shelley began writing the novel in 1824 after she learned of the death of Lord Byron, and The Last Man is notable for its idealized portraits of P. B. Shelley and Byron “in the bright days of his youth.”

No. 4.

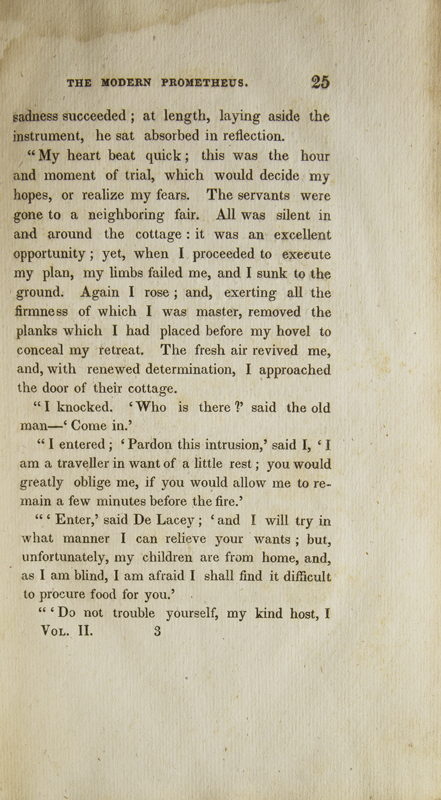

Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. By Mary W. Shelly, Author of ‘The Last Man,’ ‘Perkin Warbeck,’ &c. 2 vols., Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard, 1833. First American edition.

The origins of Frankenstein are well known. In the summer of 1816, Mary Shelley, a brilliant teenager, began her novel of a medical student who creates an artificial human being and endows him with life. Victor Frankenstein is frightened by the “daemon” he has created. The monster learns to read and speak, and confronts his maker, who rejects him. The monster pursues Frankenstein across Europe, leaving a trail of death, and chases Victor into the Arctic. With the stage production of Presumption! Or, the Fate of Frankenstein in 1823, Frankenstein’s monster stepped from the pages of Mary Shelley’s book into the world’s imagination.

No. 5.

Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. By Mary W. Shelly, Author of ‘The Last Man,’ ‘Perkin Warbeck,’ &c. 2 vols., Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard, 1833. First American edition.

Volume II is open to p. 25, where the monster speaks his first words, “Pardon this intrusion.”

No. 5.

Sara Coleridge. Phantasmion. London: William Pickering, 1837. One of 250 copies.

The first English fantasy novel set entirely in a secondary world. Sara Coleridge was the daughter of the poet S. T. Coleridge (and later editor of his work). She first told this story to her young son and wrote it during a period of ill-health compounded perhaps by her growing addiction to opium.

No. 6

Jules Verne. Around the World in Eighty Days. Translated by Geo. M. Towle. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, n.d., ca. 1876.

On a wager of staggering proportions, Phineas Fogg embarks on a trip round the world, using all of the latest technologies of the Victorian era: “I will jump — mathematically.”

An early American edition of one of the most celebrated of the Voyages extraordinaires of Jules Verne (1828-1905), whose scientific extrapolations included Captain Nemo’s submarine, floating cities, travel to the moon, and the megalomaniac aviator Robur-le-Conquérant.

No. 7.

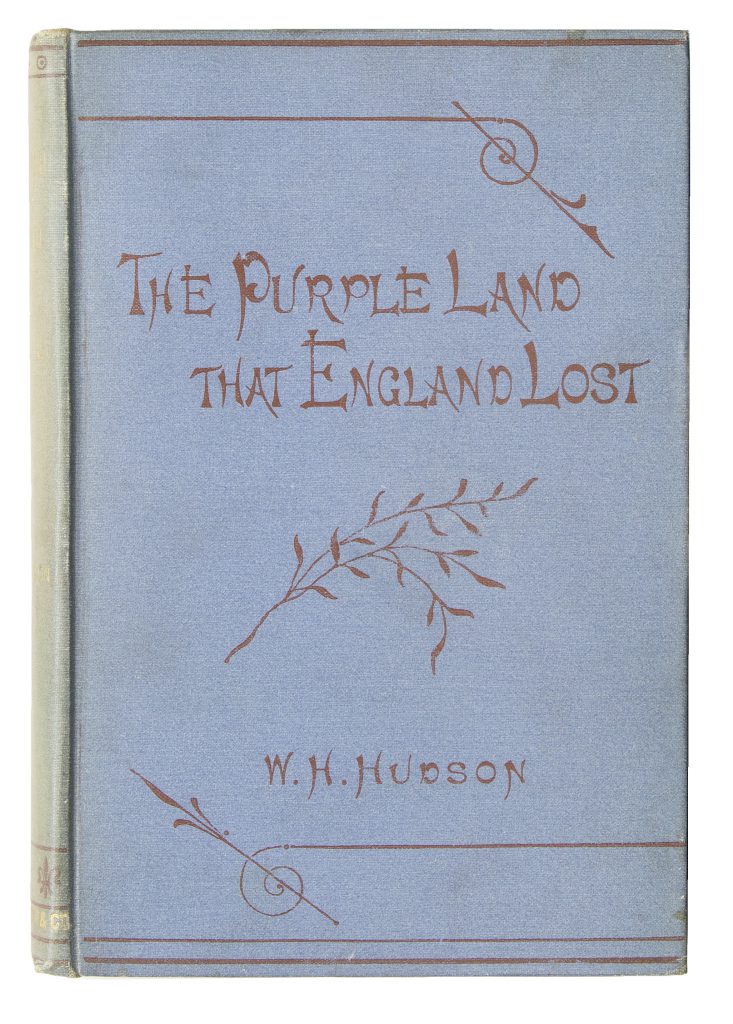

W. H. Hudson. The Purple Land That England Lost, Travels and Adventures in the Banda Oriental, South America. London: Sampson, Low, Marston, 1885.

Fantastical tales of South American life by the Argentinian-born ornithologist and author W. H. Hudson. A clear precursor of later magical realism.

Hudson is somewhat neglected today but I love this book.

The A. E. Newton copy.

No. 8.

W. H. Hudson. The Purple Land That England Lost, Travels and Adventures in the Banda Oriental, South America. London: Sampson, Low, Marston, 1885.

Fantastical tales of South American life by the Argentinian-born ornithologist and author W. H. Hudson. A clear precursor of later magical realism.

Hudson is somewhat neglected today but I love this book.

The A. E. Newton copy.

No. 8.

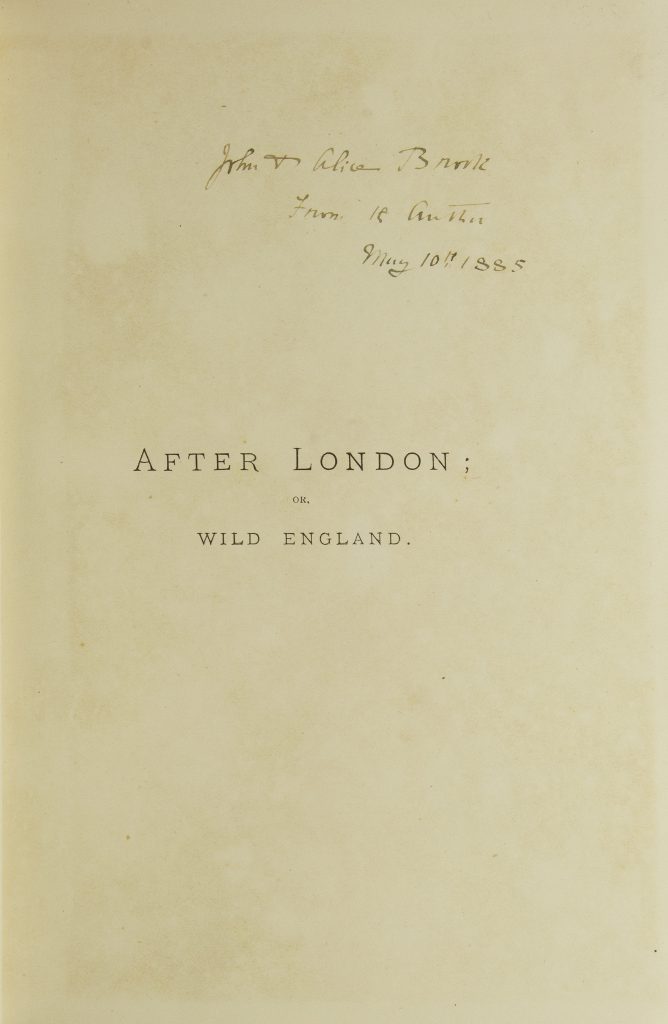

Richard Jefferies. After London; or, Wild England. [. . .] In Two Parts: Part 1 – The Relapse into Barbarism. Part II – Wild England. London: Cassell and Company, 1885.

At the height of Victorian prosperity, Richard Jefferies (1848-87) published this pioneering novel of what happens After the End of the World. The first section describes the changes “after London ended” and the second section is the original neo-mediaeval fantasia of a post-apocalyptic future. Chapter XXIII, “Strange Things,” describes a visit to the ruins of London.

No. 9.

Richard Jefferies. After London; or, Wild England. [. . .] In Two Parts: Part 1 – The Relapse into Barbarism. Part II – Wild England. London: Cassell and Company, 1885.

Presentation inscription on half title: “John & Alice Brook from the Author, May 10th 1885.”

No. 9.

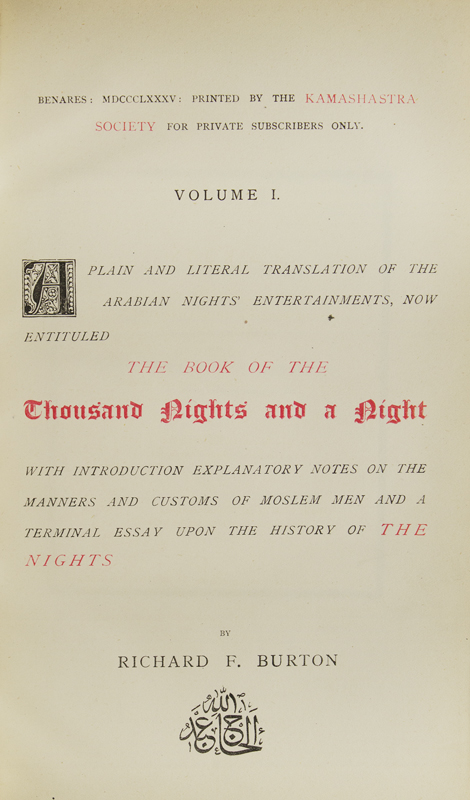

Richard F. Burton. A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments, now entitled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night. [And:] Supplemental Nights. 16 vols., Benares [i.e., London]: Printed by the Kamashastra Society for Private Subscribers Only, 1885–1888.

Burton had gained literary fame in the 1850s with the account of his pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina in disguise. This first complete English translation of the Arabian Nights, an unexpurgated and explicitly erotic work published by subscription with a false imprint, assured Burton a comfortable fortune in his later years. The Ocean of Story.

No. 10.

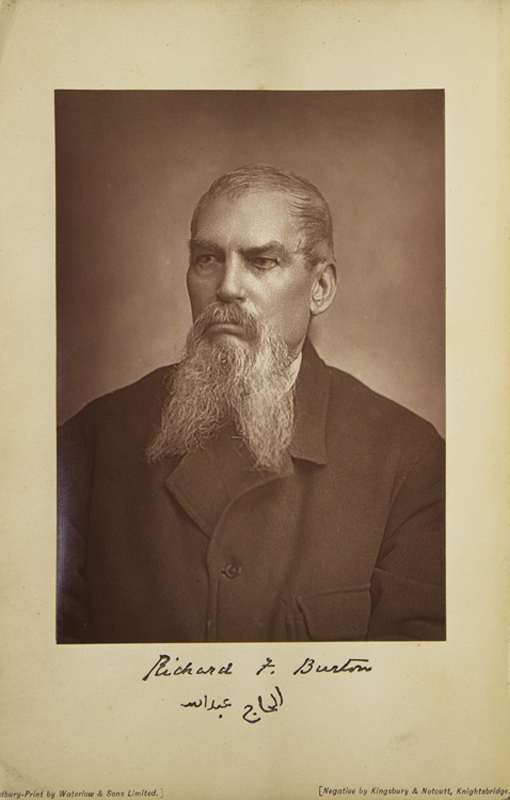

(Richard F. Burton) Woodburytype portrait of Burton by Kingsbury & Notcutt. [In:] Richard Bates, et al. A Sketch of the Career of Richard F. Burton. London: Waterlow & Sons, 1886.

Portrait of explorer, world traveller, diplomat, and translator Richard F. Burton (1821-90), about the time of the publication of the Arabian Nights.

No. 10.

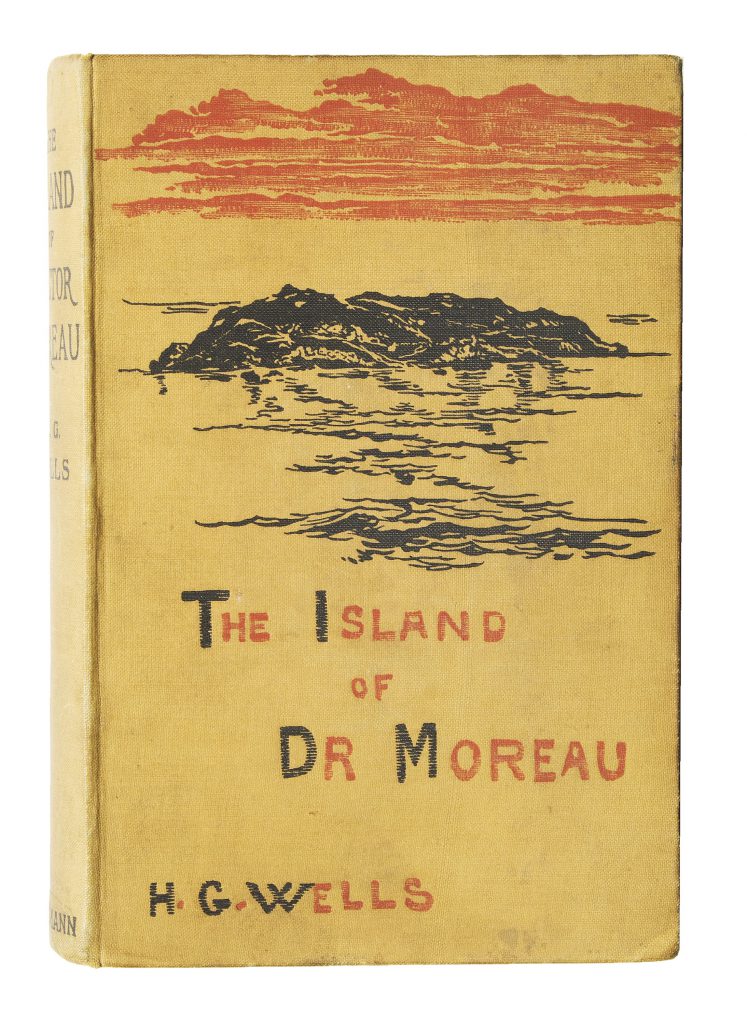

H. G. Wells. The Island of Doctor Moreau. London: William Heinemann, 1896. Stirrup bookplate of Larry McMurtry.

Rescued after a shipwreck in the south seas, Edward Prendick is brought to the remote island where Doctor Moreau has re-engineered animals into humans through vivisection and the implacable teachings of the Law:

“Not to go on all-Fours; that is the Law. Are we not Men?”

A profoundly shocking contemplation of what it means to be human.

No. 11.

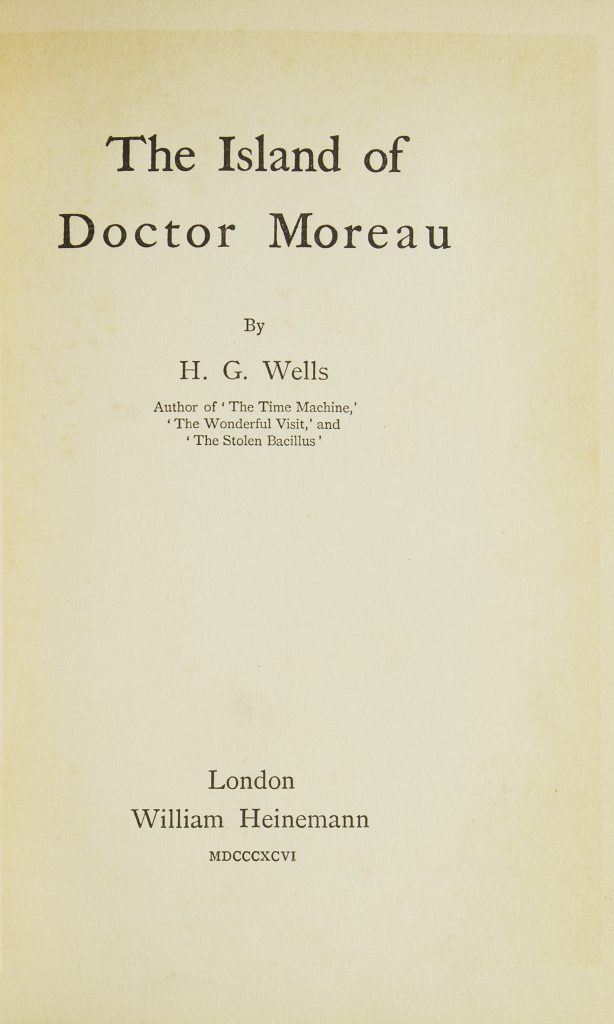

H. G. Wells. The Island of Doctor Moreau. London: William Heinemann, 1896.

“The ultimate science fiction novel” — Gene Wolfe

No. 11.

(KELMSCOTT PRESS) William Morris. The Sundering Flood. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1897. Map by H. Cribb after sketch by William Morris.

The last of the influential fantasies of William Morris, a rich imagined world of the Middle Ages.

On the front pastedown is the elegant archetype of the fantasy map that became standard issue after Pratt and Tolkien. As Diana Wynne Jones wrote in The Tough Guide to Fantasyland (1996): “you are going to have to visit every single place on this Map, whether it is marked or not.”

No. 12.

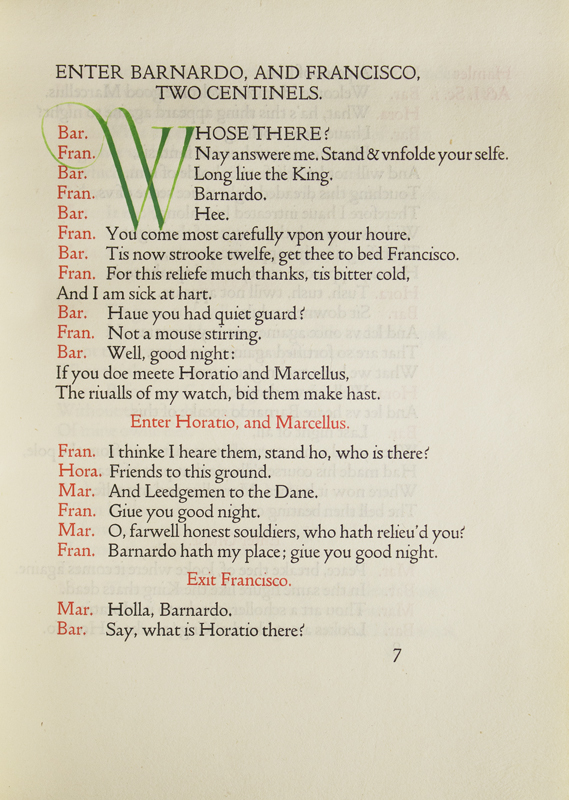

(DOVES PRESS) William Shakespeare. The Tragicall Historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmark (1604.1623). Hammersmith: Doves Press, June 1909.

A ghost story and a beautiful book from T. J. Cobden-Sanderson’s Doves Press.

With the initial “W” in apple-green calligraphic flourish by Edward Johnston.

No. 13.

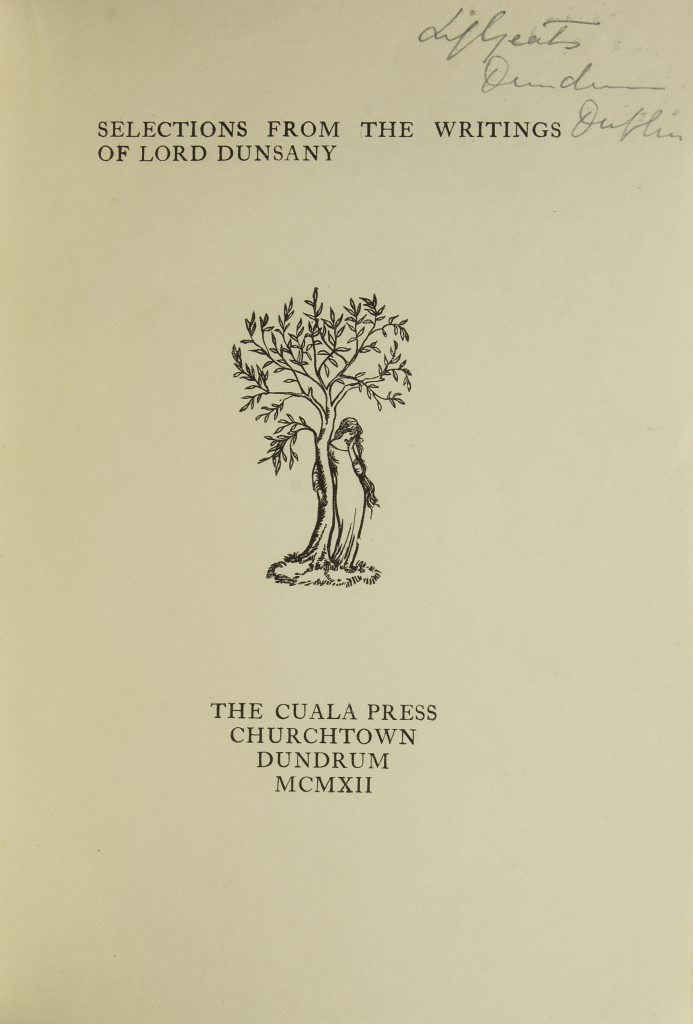

(CUALA PRESS) Lord Dunsany. Selections from the Writings of Lord Dunsany. Churchtown: Cuala Press, 1912.

Early writings by Lord Dunsany (1878-1957), with an introduction by William Butler Yeats, “printed by village girls at Dundrum,” to remind us that there is no separation between the literary and the fantastical.

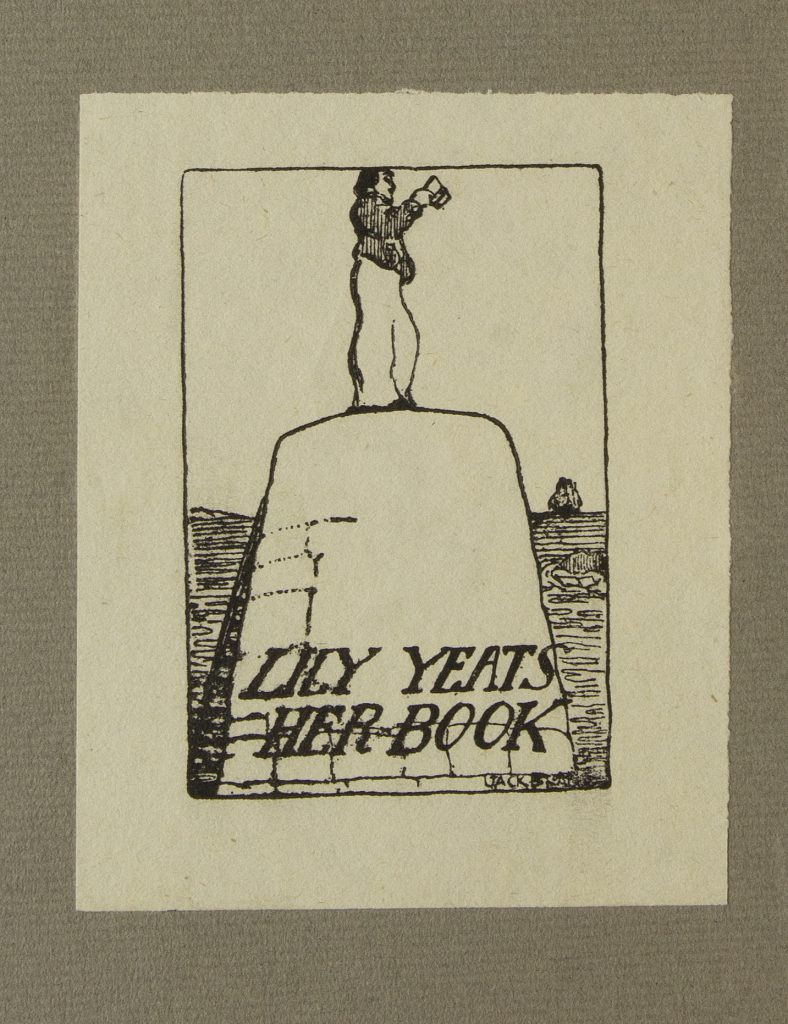

Lily Yeats’ copy with her bookplate and ownership note on the title page, “Lily Yeats her book.”

No. 14.

(CUALA PRESS) Lord Dunsany. Selections from the Writings of Lord Dunsany. Churchtown: Cuala Press, 1912.

Lily Yeats’ copy with her bookplate and ownership note on the title page, “Lily Yeats her book.”

No. 14.

Contents

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed