William Crawford and D. R. Welch. Science Fiction Bibliography. Vol. 1, No. 1. [All published]. Austin, Texas: The Science Fiction Syndicate, 509 West 26th Street, 1935.

“This brief pamphlet is neither complete nor entirely accurate . . .”

The first bibliography of science fiction, chiefly devoted to chapbooks and fanzines in the first decade after the rise of American pulp science fiction.

No. 25.

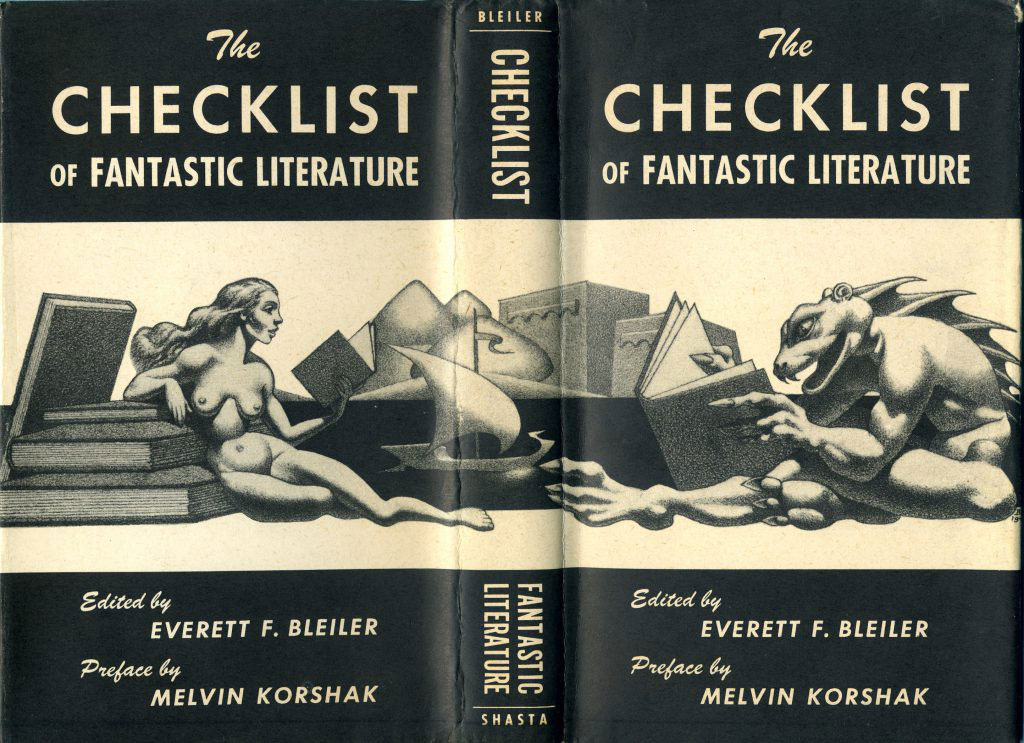

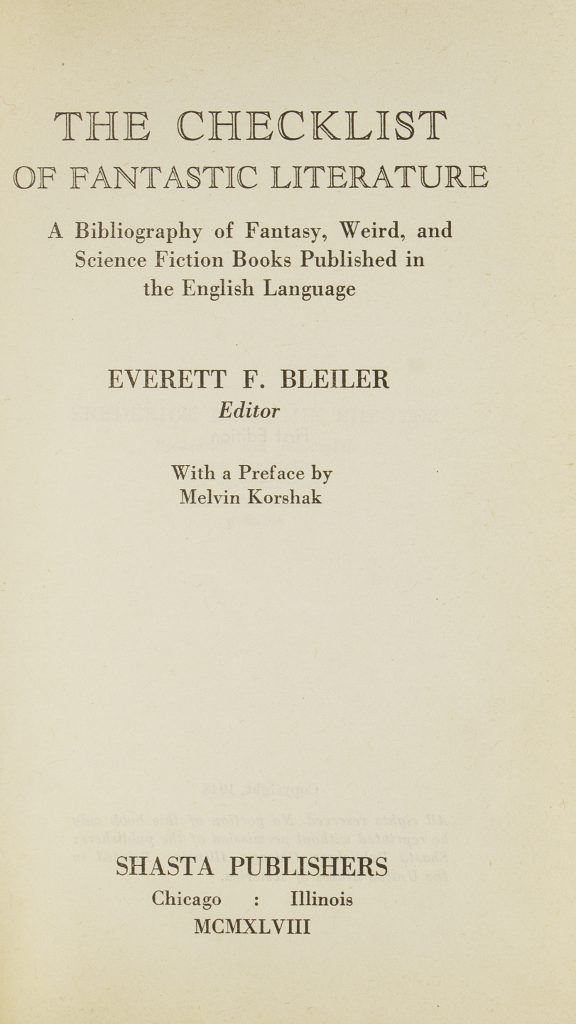

Everett F. Bleiler, editor. The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. A Bibliography of Fantasy, Weird, and Science Fiction Books Published in the English Language. Chicago: Shasta, 1948.

The first comprehensive attempt at science fiction bibliography, by E. F. Bleiler, who later became an important editor and anthologist.

With a superb dust jacket illustration by Hannes Bok.

No. 31.

Everett F. Bleiler, editor. The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. A Bibliography of Fantasy, Weird, and Science Fiction Books Published in the English Language. Chicago: Shasta, 1948.

The first comprehensive attempt at science fiction bibliography, by E. F. Bleiler, who later became an important editor and anthologist.

No. 31.

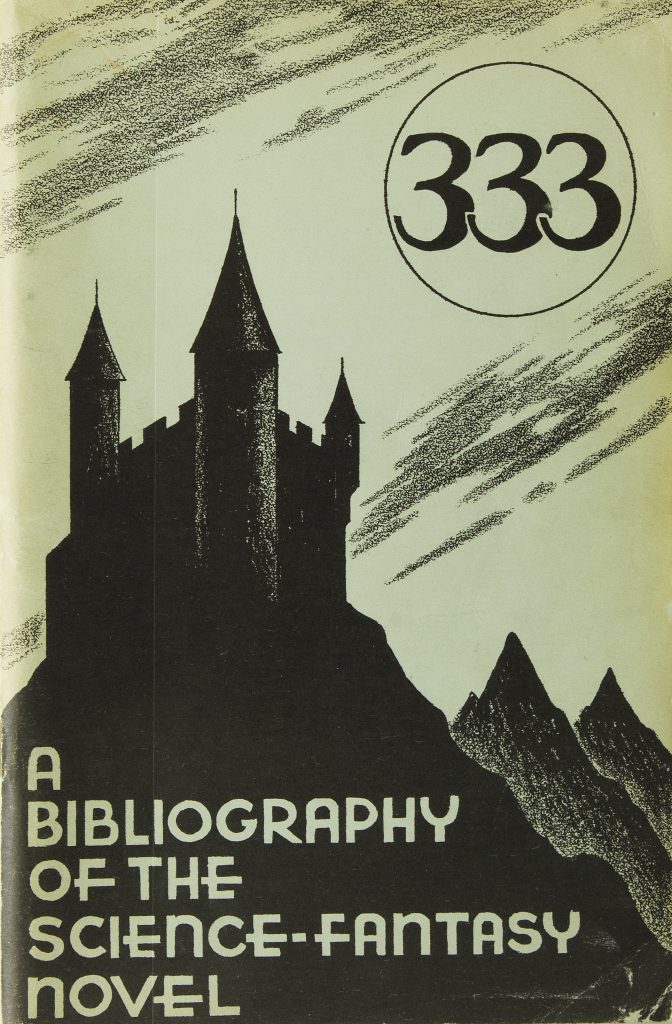

Joseph Crawford, Jr., James J. Donahue, and Donald M. Grant. “333” A Bibliography of the Science-Fantasy Novel. Providence: Grandon, 1953.

Annotated listing of fantastical works from Walpole through 1950, grappling with issues of definition and identifying nine categories of novels: the gothic Romance, the weird tale, science fiction, fantasy, the lost race, fantastical adventure, unknown worlds, the oriental tale, and “associational”. The discussion of Frankenstein begins succinctly, “A Swiss medical student, Victor Frankenstein, creates an artificial human being.”

See A Conversation, pp. 209-210.

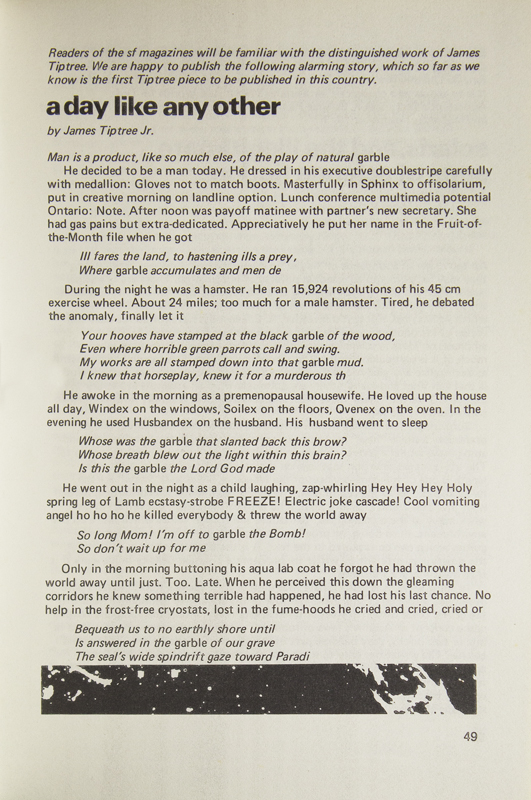

Alice Sheldon. “A Day Like Any Other,” [in:] Foundation 3 (1973).

The first British publication by James Tiptree, Jr., “A Day Like Any Other,” written in 1968, contains, in miniature and hiding in plain sight, all the concerns of its author, Alice Sheldon.

The James Tiptree, Jr., award is given in her memory to work exploring gender roles.

Sheldon’s life was as fantastical as anything Tiptree ever wrote. Julie Phillips’ exemplary biography, James Tiptree, Jr. The Double Life of Alice Sheldon, published in 2006, won the Hugo award.

No. 44.

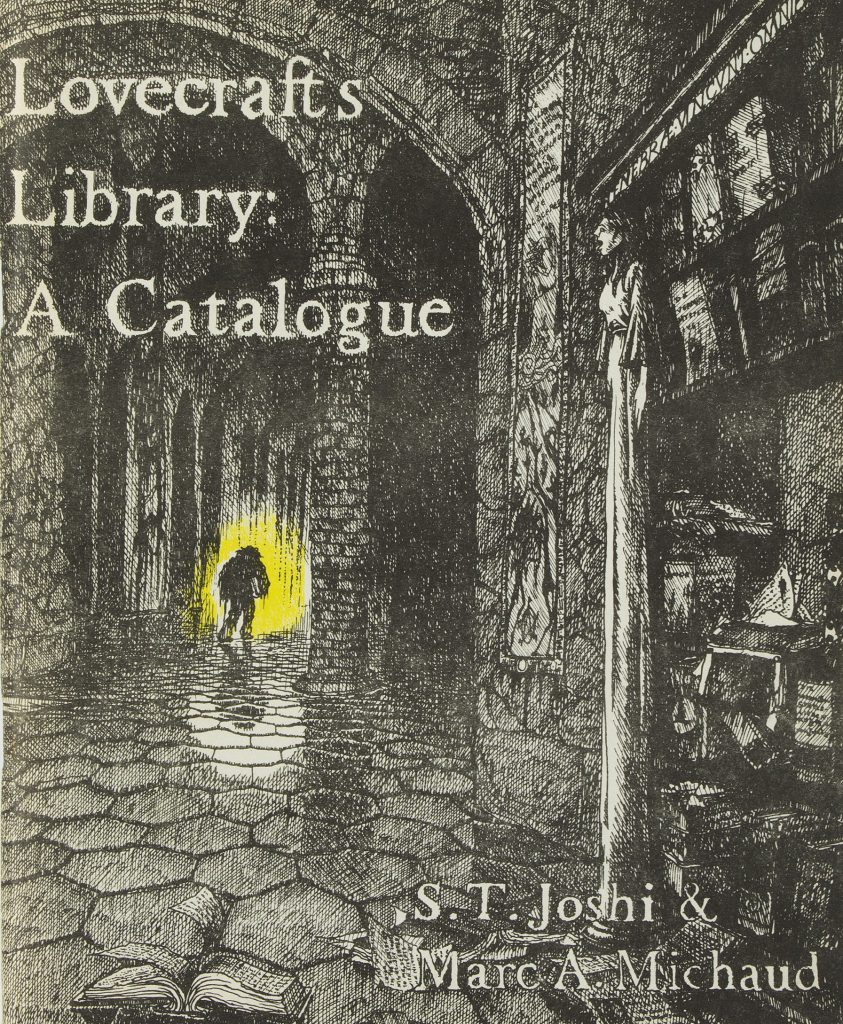

(H. P. Lovecraft) S. T. Joshi and Marc Michaud. Lovecraft’s Library: A Catalogue. West Warwick, R.I.: Necronomicon Press, 1980.

Early publication of the prolific Lovecraft scholar S. T. Joshi. The entry on The Lock and Key Library (1909), edited by Julian Hawthorne, points to the way in which Lovecraft’s essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927) essentially defined a new genre and a new way of looking at literature through his careful reading in these volumes. Until Lovecraft, these stories were viewed as a subset of the mystery field: it is no longer possible to do so.

No. 22.

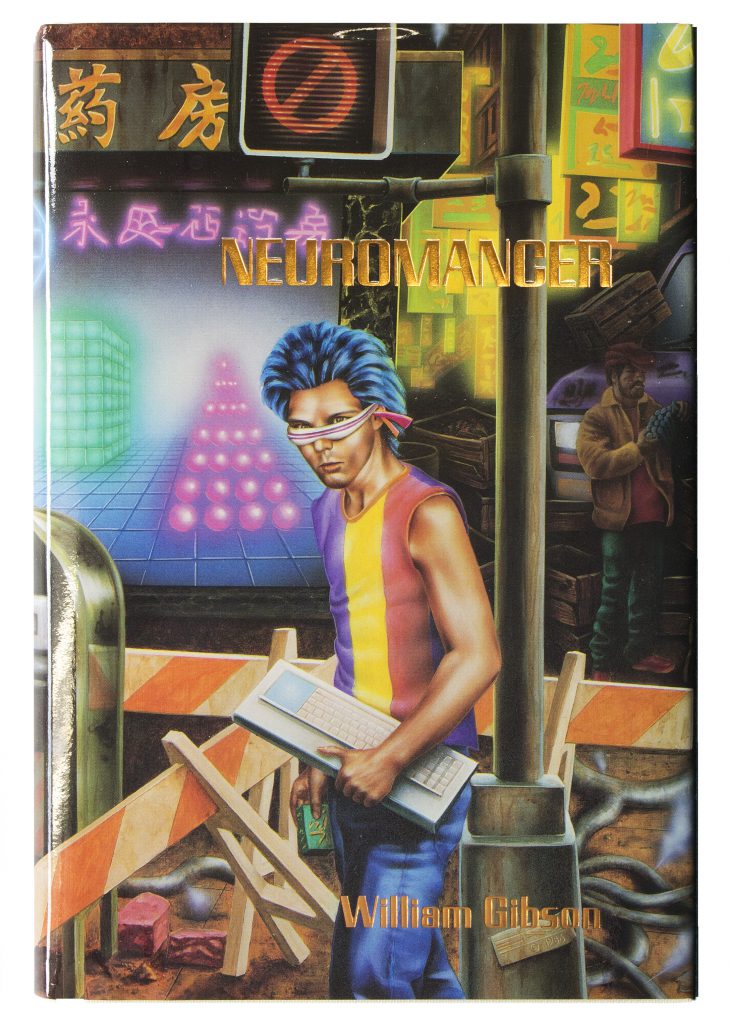

William Gibson. Neuromancer. West Bloomfield, Michigan: Phantasia Press, 1986. Pictorial dust jacket.

Note the kinetic, and high-information painting by Barclay Shaw for the dust jacket: the scene is neon post-Bowie noir, full of urban menace and suggestion, with semiotic teasers and colored geometries. On this front panel, a young man holds a keyboard.

The dust jacket is not the text but the context of the book. Bibliography, like science fiction, as close observation of the present.

No. 51.

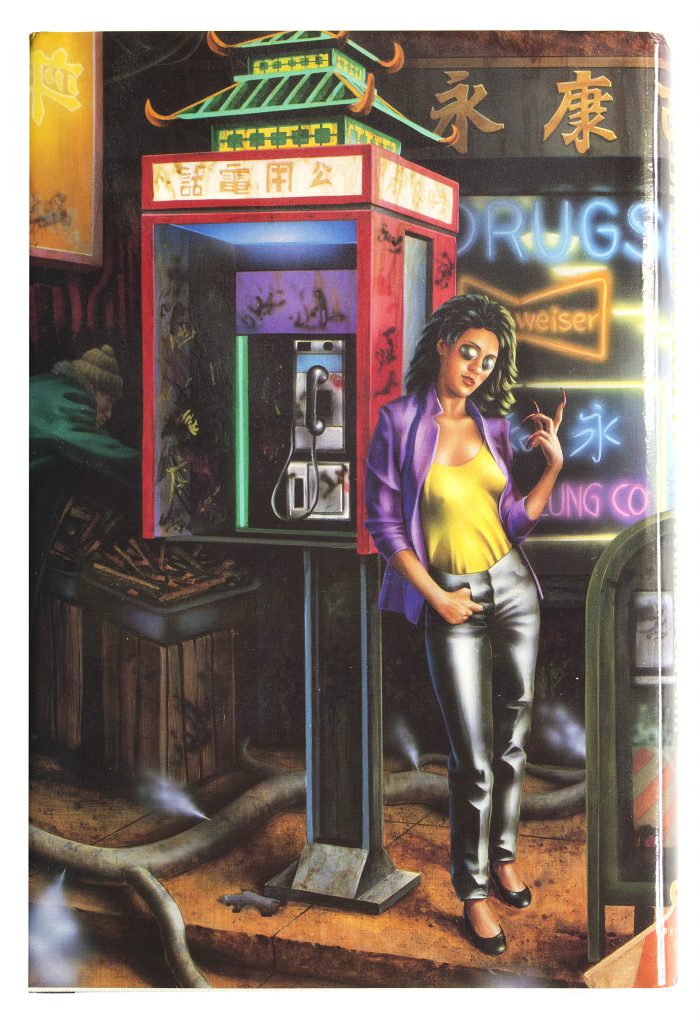

William Gibson. Neuromancer. West Bloomfield, Michigan: Phantasia Press, 1986. Pictorial dust jacket.

Note the kinetic, and high-information painting by Barclay Shaw for the dust jacket: the scene is neon post-Bowie noir, full of urban menace and suggestion, with semiotic teasers and colored geometries. On this back panel, a young woman with artificial eyes leans against a pay phone.

The dust jacket is not the text but the context of the book. Bibliography, like science fiction, as close observation of the present.

No. 51.

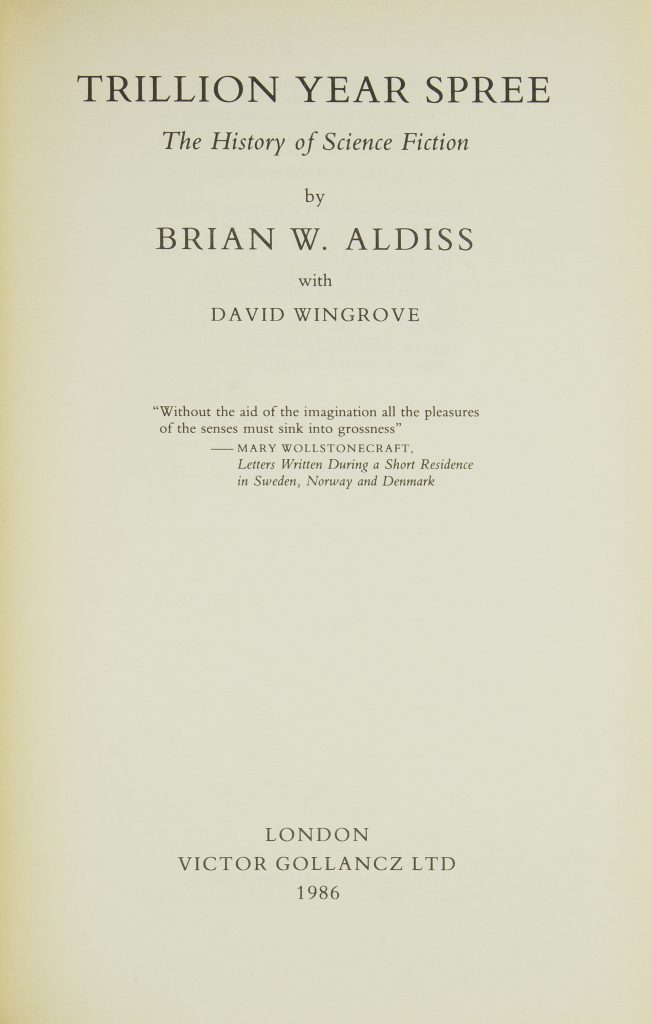

Brian W. Aldiss, with David Wingrove. Trillion Year Spree. The History of Science Fiction. London: Gollancz, 1986.

In 1973, Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) published Billion Year Spree, a history of the field notable for its advocacy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the key text in science fiction. This expanded edition is a colorful and often funny book, with portraits of writers, written by an “impartial insider,” who had been at the heart of British science fiction since the mid-1950s.

No. 53.

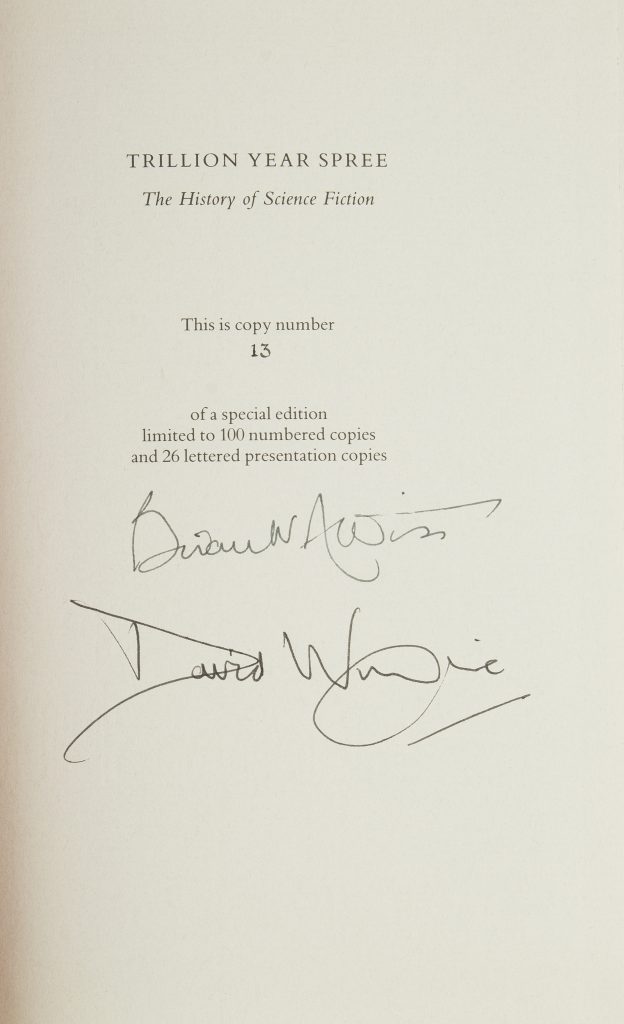

Brian W. Aldiss, with David Wingrove. Trillion Year Spree. The History of Science Fiction. London: Gollancz, 1986.

In 1973, Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) published Billion Year Spree, a history of the field notable for its advocacy of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as the key text in science fiction. This expanded edition is a colorful and often funny book, with portraits of writers, written by an “impartial insider,” who had been at the heart of British science fiction since the mid-1950s.

One of 100 numbered copies, signed by the authors, with an introduction by Aldiss not published in the trade edition.

No. 53.

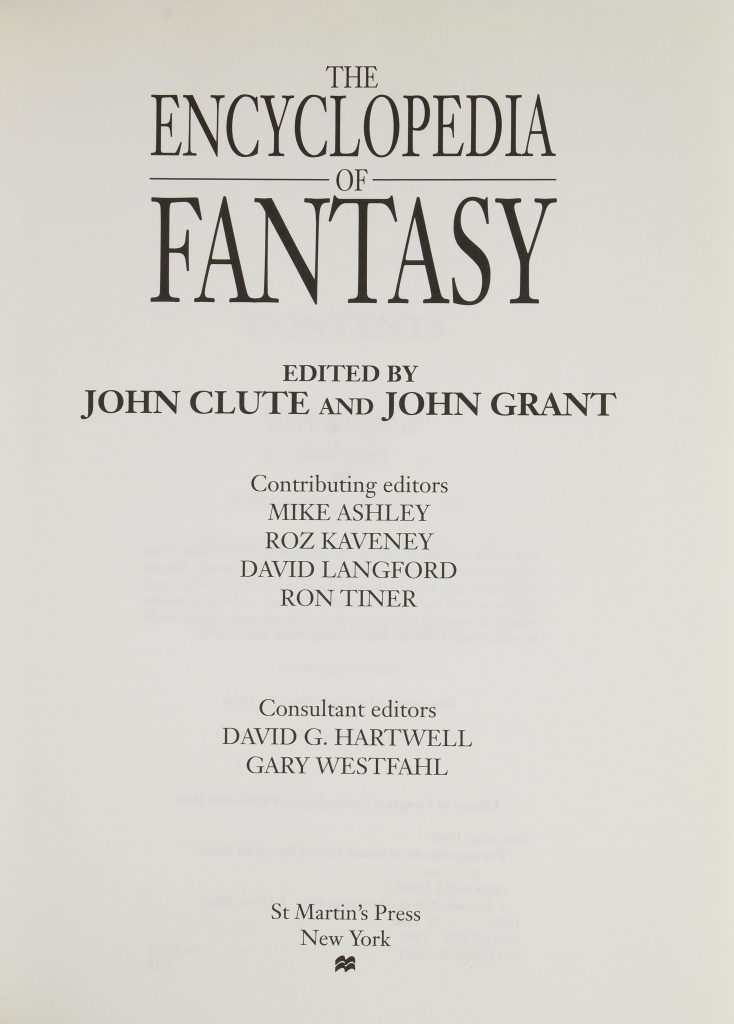

John Clute and John Grant, editors. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

John Clute, Canadian-born author long resident in London, is a brilliant critic of science fiction and what he calls “fantastika,” or “that wide range of fictional works whose contents are understood to be fantastic.”

To produce an Encyclopaedia is essentially a political act: to strike a spark into the tinder-dry edifice of the ancien régime (in the case of Diderot’s Encyclopédie), or, in the case of The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, to throw open the doors of the labyrinth and propose a new way of approaching the literature of the fantastic. Clute embeds a revolutionary vocabulary of criticism within The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, in such entries as Polder, Thinning, Belatedness, Arabian Nightmare, Crosshatch, Little, Big, and Recognition.

Clute is also the prime mover of the vast and authoritative Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (or SFE), now an online resource. It is impossible to consider the recent history of the field without encountering Clute’s ideas and writings.

No. 60.

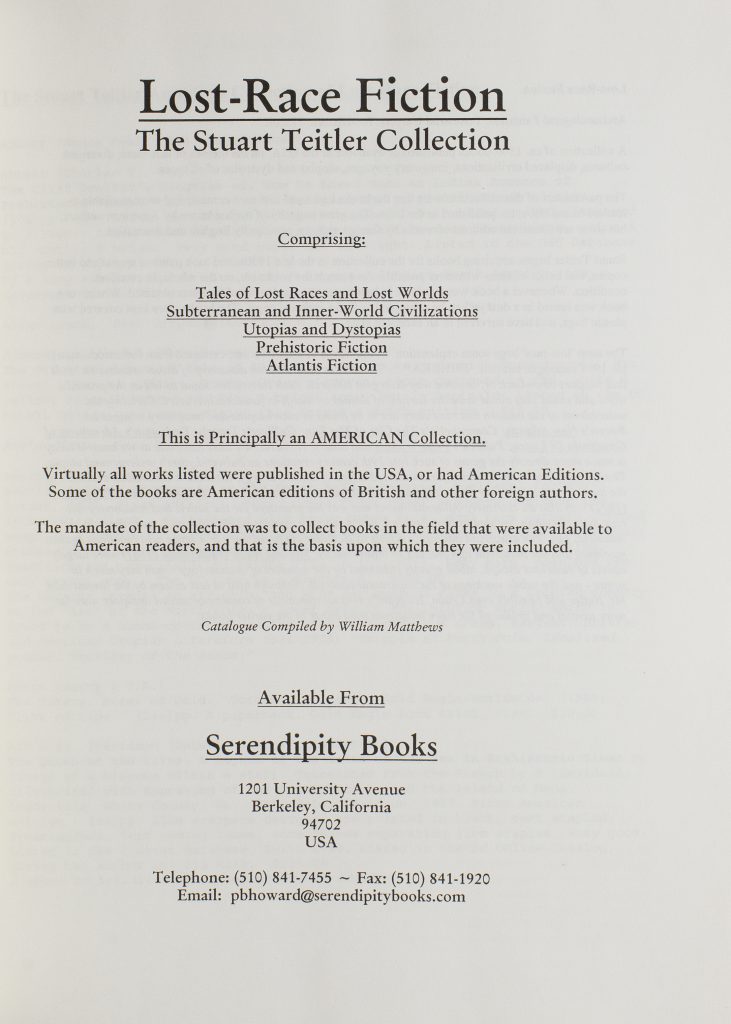

William Mathews. Lost-Race Fiction. The Stuart Teitler Collection. Comprising Tales of Lost Races and Lost Worlds, Subterranean and Inner-World Civilizations, Utopias and Dystopias, Prehistoric Fiction, Atlantis Fiction. Berkeley: Serendipity Books, 2001.

Catalogue of the American lost-race fiction of west coast book scout and collector Stuart Teitler (1940-2012), whose axiom was “don’t look for books, look at them.” Teitler was contemptuous of the well-trodden pathways of collecting, and was also reputed to be indifferent to condition. The lost-race genre had its heyday from the 1870s to the aftermath of the Second World War.

Published by Berkeley bookseller Peter Howard in an edition of ten copies.

No. 65.

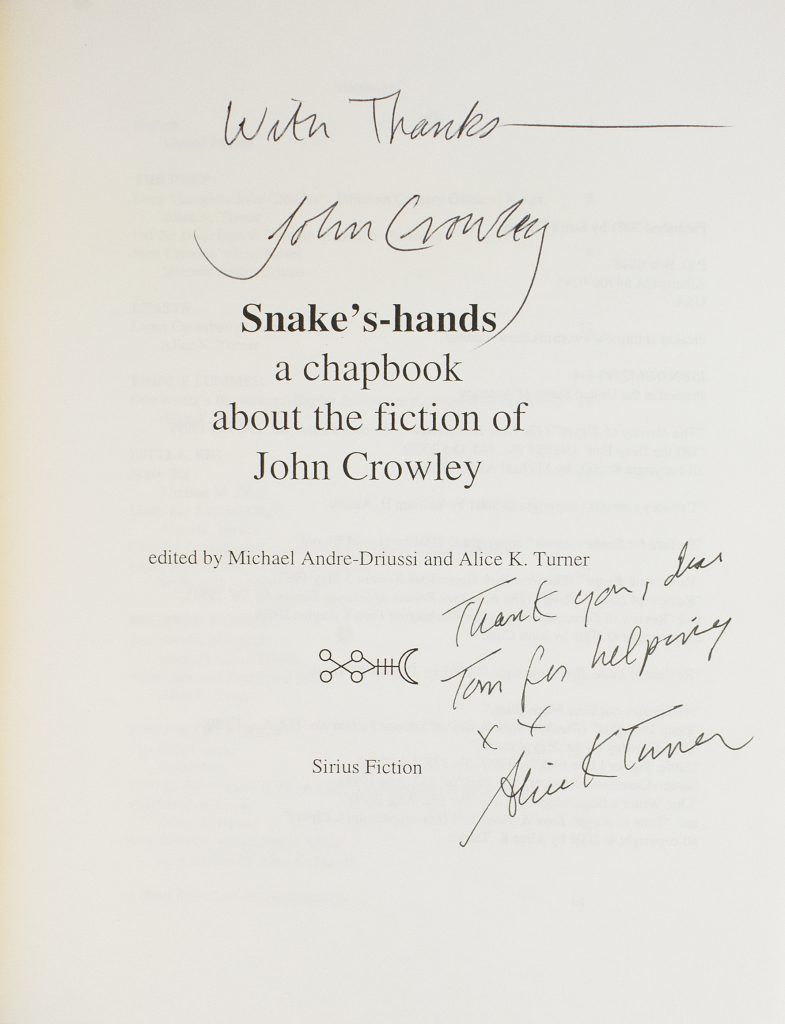

(John Crowley) Michael Andre-Driussi and Alice Turner, editors. Snake’s-hands. A chapbook about the fiction of John Crowley. Albany, California: Sirius Fiction, 2001.

Snake’s-hands includes an introduction by Harold Bloom, and essays by the editors, John Clute, Thomas M. Disch, and others.

Inscribed to Tom Disch.

See no. 50.

Susanna Clarke. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. New York: Bloomsbury, 2004.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell invokes magic in Britain during the Napoleonic Wars, but it is an English magical tradition which Clarke has invented that confers power upon its practitioners. Like Lord Byron, the magician Jonathan Strange derives his power from the manipulation of words. The tradition seems to fit into the known historical and literary and social fabric of our world. This closeness is by turn whimsical and deadly serious, and it is deceptive, for Clarke’s novel constitutes an extension of the geography of imagined lands. The house of Lost-hope, and its doleful corridors, and the fact “that Piccadilly stood in close proximity to a magical wood,” are potent additions to the gazetteer of fantasy. Books are integral to Clarke’s tale.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell won the Hugo and World Fantasy awards.

No. 66.

John Clute. The Darkening Garden. A Short Lexicon of Horror. Seattle: Payseur & Schmidt, 2006.

With: Postcards of Doom. A Journey from Affect to Vastation. Thirty artists, thirty motifs. Seattle: Payseur & Schmidt, 2006.

The Darkening Garden builds upon Clute’s distinctive critical vocabulary, and its definitions are so rich in allusion that it functions as an encyclopaedia in miniature. In its discussion of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Clute demonstrates his willingness to reassess earlier findings. This edition was illustrated by thirty artists, each illustrating a descriptive term. The Postcards of Doom reproduce the illustrations and were issued as a set in conjunction with The Darkening Garden.

No. 60.

Robert Eldridge. When Books Kaleidoscope or The Catalogue That Time Forgot. In Remembrance of Stuart Teitler (1940–2012). Elizabethtown, New York: Gloomhaven Press, 2012.

With a memoir of west coast book scout and collector Stuart Teitler (1940-2012).

No. 65.

Contents

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed