Pierre Benoît. L’Atlantide. Roman. Paris: Michel Albin, 1919. Yellow printed wrappers.

L’Atlantide is a fantasy of scientific ecstasy: the discovery of a lost world in the great empty space at the limit of cartographic knowledge. In the desert fastnesses of the Sahara, Atlantis survives and is ruled by a sexy, powerful queen. I read this novel of exotic lands and exotic languages in high school and never forgot.

No. 15.

Pierre Benoît. L’Atlantide. Roman. Paris: Michel Albin, 1919.

Title page of the first edition.

No. 15.

Pierre Benoît. Atlantida (L’Atlantide). Translated by Mary C. Tongue and Mary Ross. New York: Duffield, 1920.

Translation of Benoît’s novel of Atlantis in the Blad el-khouf, the Country of Fear, in the remote mountains of the Sahara. Atlantida is a vast and subtle lever that raised Atlantis from darkest protohistory back into popular awareness. The book was filmed several times and other writers followed with works on Atlantean themes through the 1920s and 1930s.

Dust jacket of the Duffield edition.

No. 15.

Pierre Benoît. Atlantida (L’Atlantide). Translated by Mary C. Tongue and Mary Ross. New York: Duffield, 1920.

Title page of the first American edition.

No. 15.

Stella Benson. Living Alone. London: Macmillan, 1920.

The intrusion of a witch into the drudgery of London life during wartime. Benson’s witch moves easily between Hyde Park and Faery, which can also be reached by an easy commuter train from London. The House of Living Alone is a magical store and boarding house, and throughout the novel Benson mocks polite society and those who have forgotten that magic exists.

First published in 1919.

No. 16.

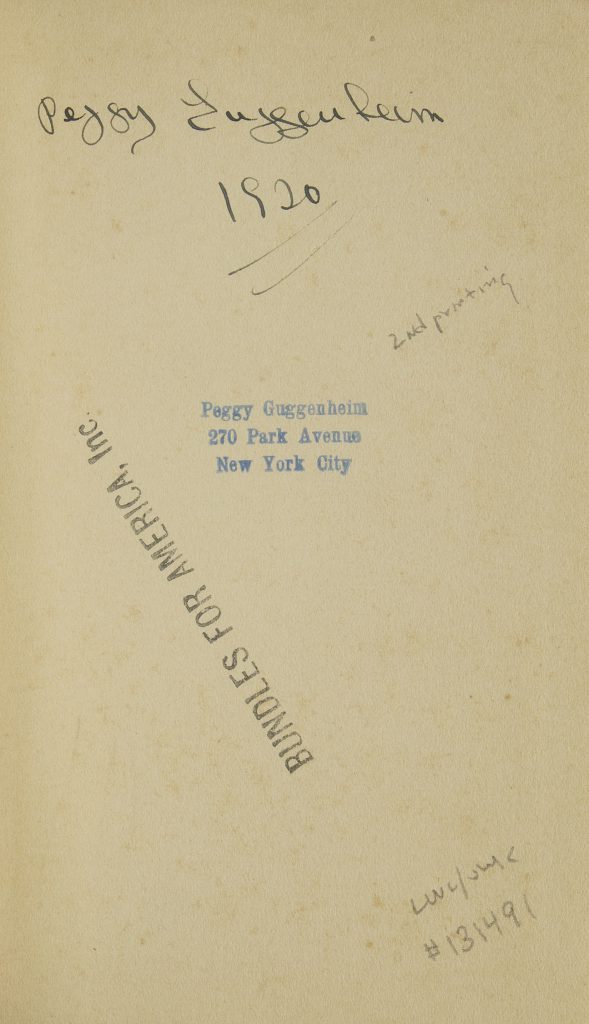

Stella Benson. Living Alone. London: Macmillan, 1920.

Second printing (originally published 1919).

With the ownership signature of Peggy Guggenheim, 1920, on flyleaf.

No. 16.

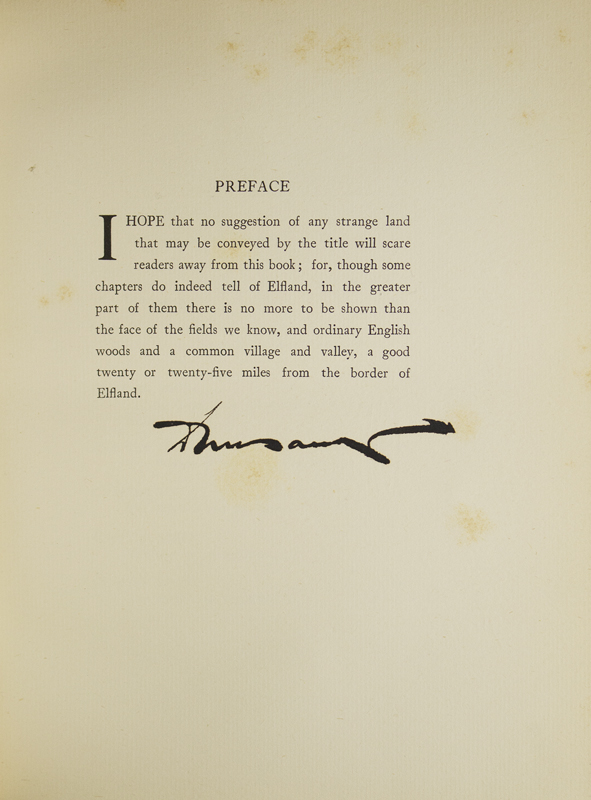

Lord Dunsany. The King of Elfland’s Daughter. London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924. Large paper copy, one of 250, signed by the author at the Preface.

Dunsany’s masterpiece, a tale of yearning and loss. The prose calls to be read aloud, the images are sharp, and there are some very funny passages. Alveric comes to Elfland and woos the King’s daughter, Lirazel, who flees with Alveric to “the fields we know,” her diadem of ice melting as she crosses the border. Lirazel bears a son, but she can never really get the hang of ordinary human life. One day blows away with the autumn leaves, back to Elfland. Once there, she pines for the human life she knew.

No. 17.

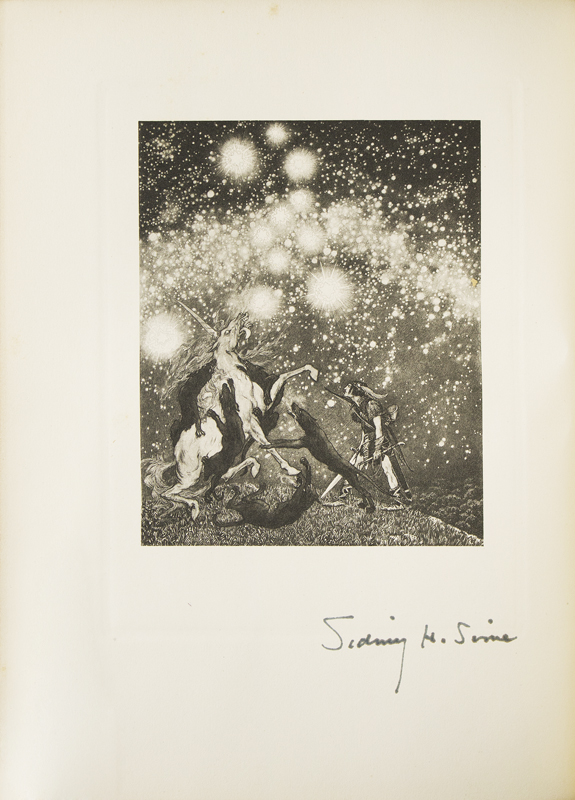

Lord Dunsany. The King of Elfland’s Daughter. London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924. Large paper copy, one of 250 copies.

The photogravure frontispiece, signed by artist Sidney H. Sime.

No. 17.

Lord Dunsany. The King of Elfland’s Daughter. London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924. Large paper copy, one of 250 copies.

The dust jacket, with illustrations by artist Sidney H. Sime, is very rare.

No. 17.

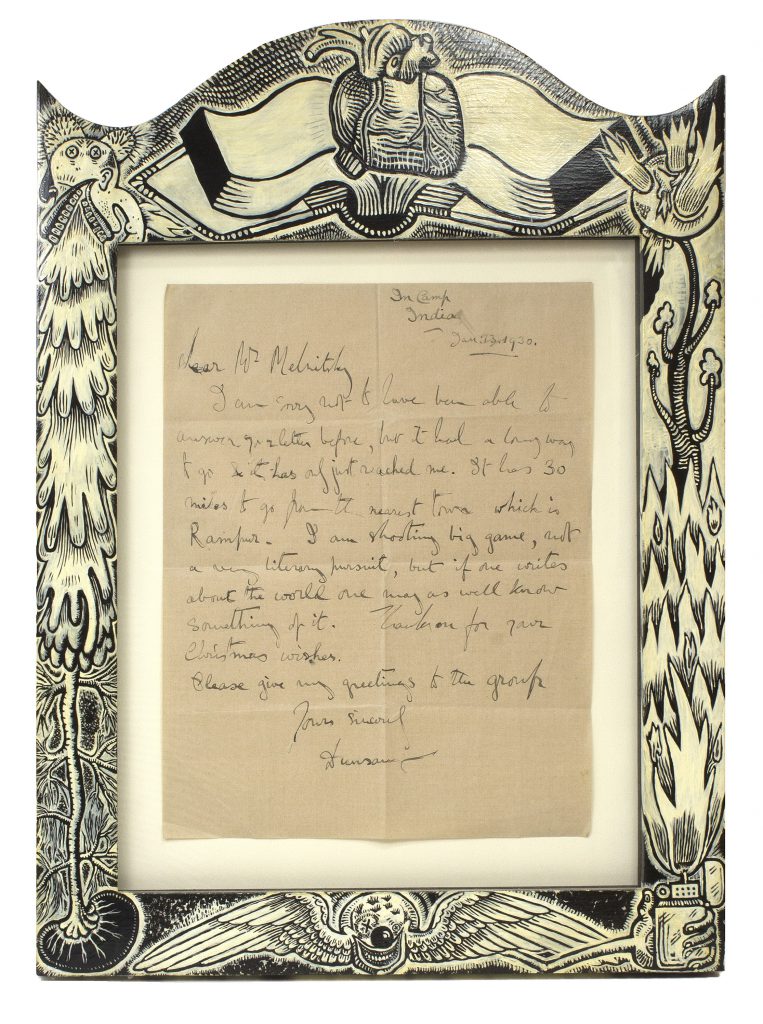

Lord Dunsany. Autograph letter, signed, In Camp, India, Jan. 13, 1930. In a hand-painted vernacular American Gothic frame, signed by cowpunk musician Stephen Fredette, 1994.

“I am shooting big game, not a very literary pursuit, but if one writes about the world, one may as well see something of it.”

This letter, written somewhere in India, evokes for me Dunsany’s tall tales of Joseph Jorkens at the Billiards Club, which often involve travel in remote areas.

H. P. Lovecraft’s praise of Dunsany’s work and Lin Carter’s paperback editions of Dunsany in the 1970s ensured that subsequent generations of American readers of fantasy and horror revered him.

No. 17.

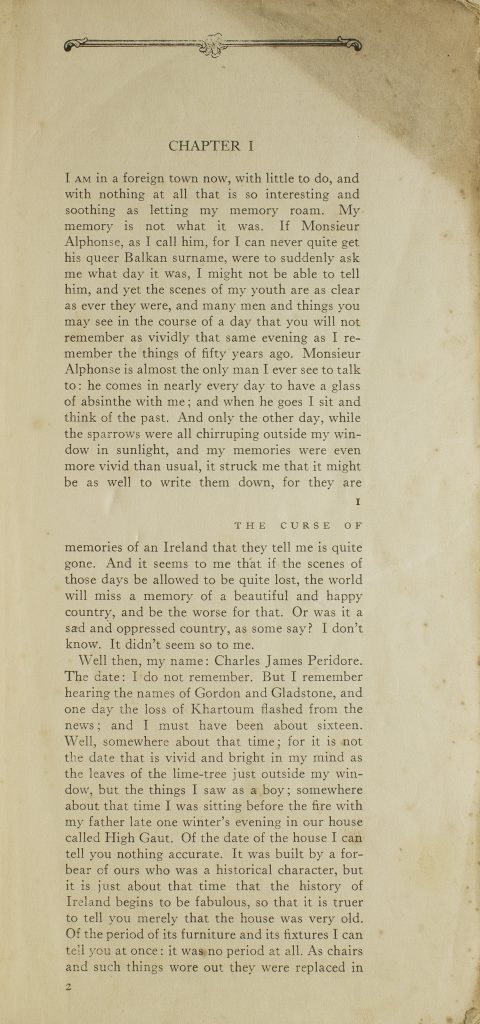

Lord Dunsany. The Curse of the Wise Woman. Long galley proofs, marked by the author for corrections. Published by William Heinemann, 1933.

Dunsany’s evocative and highly autobiographical novel of Ireland in the late 1880s. A supernatural and an ecological tale: the wise woman who lives at the edge of the red bog resists the Peat Syndicate’s plans to mine the bog.

And in the first three chapters, the narrator, an exile living in a Balkan city, uses the words silence, exile, and cunning, from which one might infer that Dunsany was not unaware of James Joyce.

No. 17.

Hope Mirrlees. Lud-in-the-Mist. London: W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., [1926].

Lud-in-the Mist is a beautifully written tale of the rediscovery of magic. Hope Mirrlees (1887-1978) plays with the conceits of the fairy story, but has created her own fully imagined world. As Michael Swanwick observes, Lud-in-the-Mist “is a dissident work, written in full awareness of what the proper literary writers were up to, and in its refusal to go along with them daringly defiant.”

One of the great fantasy novels of the interwar period, the book was reprinted in the 1970s and influenced new generations of writers, including Joanna Russ, Neil Gaiman, Elizabeth Hand, and many others.

No. 18.

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman. London: Chatto & Windus, 1926.

Lolly Willowes is a chronicle of the power of refusal. As a dependent in her brother’s house, Laura “Lolly” Willowes finds her world constricted. “She actually had a sensation that she was stitching herself into a piece of embroidery with a good deal of background.” She takes lodgings in the Shropshire village of Great Mop, and after a midnight country dance, she meets the devil in a small, empty field.

No. 19.

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman. London: Chatto & Windus, 1926.

With an autograph quotation, signed: “Sylvia Townsend Warner ‘Laura hated ink’ p. 210”.

No. 19.

Sylvia Townsend Warner. Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman. London: Chatto & Windus, 1926.

Another copy, in original printed dust jacket.

No. 19.

E. M. Forster. The Eternal Moment and other Stories. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1928.

Collection of short stories including “The Machine Stops,” Forster’s tale of a hyper-connected world — where mediated or virtual communication has replaced direct personal contact — and its collapse. Forster intended it “as a counter-blast to one of the heavens of H. G. Wells.”

No. 20.

John Buchan. The Runagates Club. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1928.

‘Every adventure takes place chiefly inside the head of somebody.’

Collection of stories from the heart of Mayfair Clubland, tales of comic misadventure, antiquarian curiosity, and other, subtler forms, including an ambiguous ghost story of the South African veldt, and “The Loathly Opposite,” one of the earliest tales of modern information warfare and mathematical cryptography. The recurring effect of The Runagates Club is to suggest that the world is not so orderly as people usually think.

No. 21.

H. P. Lovecraft. The Shunned House. Preface by Frank Belknap Long, Jr. Athol, Mass.: Published by Paul Cook The Recluse Press, 1928.

H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) was a regular contributor to Weird Tales and other pulp magazines, and was a prolific letter writer where he often expounded the cosmic materialism underlying his tales.

The Shunned House is an antiquarian tale of horror in an old house in Providence. In a direct line from the conventions of the original Gothic novels, the narrator faints at the height of the action.

Lovecraft’s first book, printed by his friend but not published during his lifetime.

No. 22.

Contents

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed