H. P. Lovecraft. The Shunned House. Preface by Frank Belknap Long, Jr. Athol, Mass.: Published by Paul Cook The Recluse Press, 1928.

H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) was a regular contributor to Weird Tales and other pulp magazines, and was a prolific letter writer where he often expounded the cosmic materialism underlying his tales.

The Shunned House is an antiquarian tale of horror in an old house in Providence. In a direct line from the conventions of the original Gothic novels, the narrator faints at the height of the action.

Lovecraft’s first book, printed by his friend but not published during his lifetime.

No. 22.

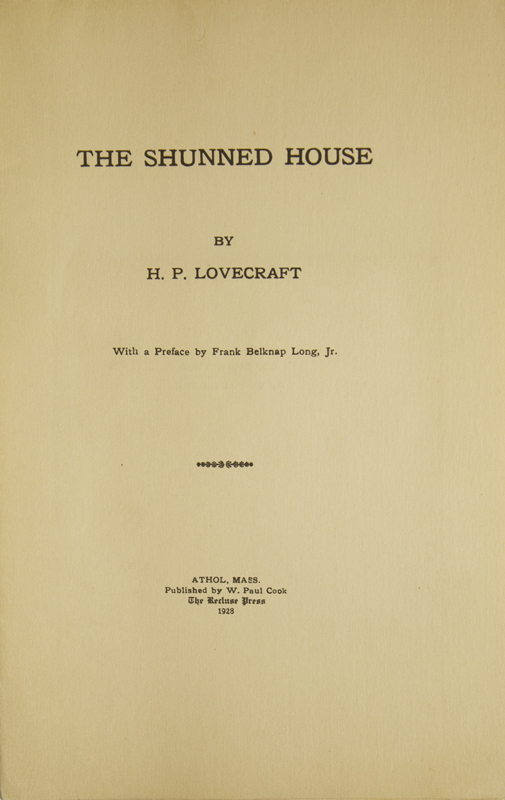

(H. P. Lovecraft) Corwin Stickney, editor. Amateur Correspondent. Vol. 2, No. 1, May–June 1937. Belleville, New Jersey, 1937.

Memorial portrait of H. P. Lovecraft by Virgil Finlay, first published by a young fan from New Jersey.

Lovecraft’s place in the American fantastical tradition was secure among his fans and readers at the time of his death, two of whom founded Arkham House to bring his work into print. It would take another sixty years before H.P.L. began to be noticed in the mainstream.

No. 22.

(H. P. Lovecraft) Paul Cook. In Memoriam Howard Phillips Lovecraft. Recollections Appreciations Estimates. Driftwind Press, 1941.

A moving testimonial of friendship, hand printed in Vermont by the author in an edition of 94 copies.

No. 22.

(H. P. Lovecraft) S. T. Joshi and Marc Michaud. Lovecraft’s Library: A Catalogue. West Warwick, R.I.: Necronomicon Press, 1980.

Early publication of the prolific Lovecraft scholar S. T. Joshi. The entry on The Lock and Key Library (1909), edited by Julian Hawthorne, points to the way in which Lovecraft’s essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927) essentially defined a new genre and a new way of looking at literature through his careful reading in these volumes. Until Lovecraft, these stories were viewed as a subset of the mystery field: it is no longer possible to do so.

No. 22.

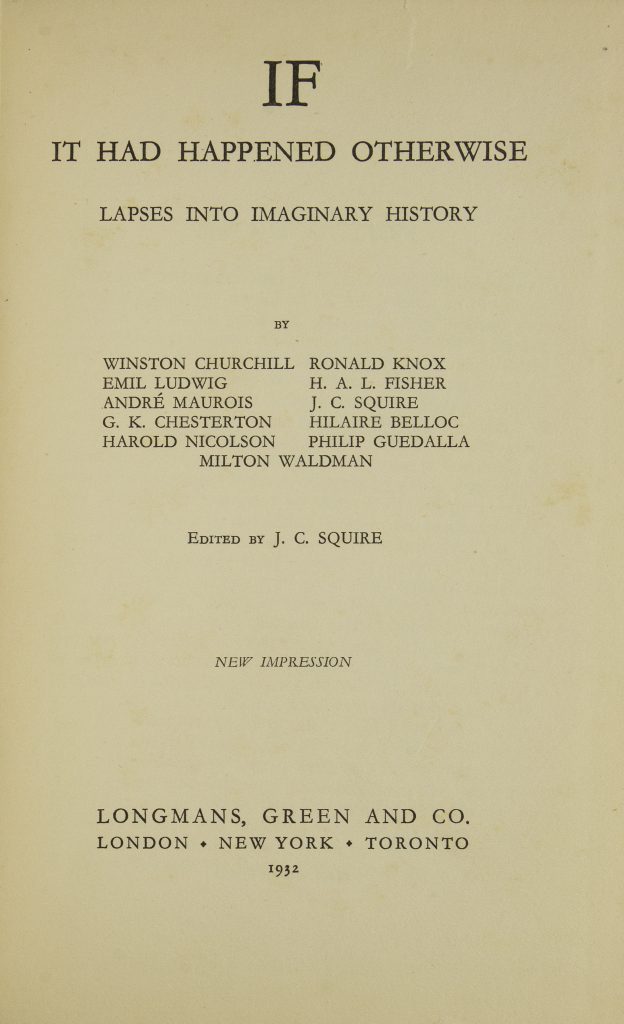

J. C. Squire, editor. If It Had Happened Otherwise. Lapses into Imaginary History. London: Longmans, 1932.

One of the “Sources of the Nile” of alternate history.

With a notable contribution by Winston S. Churchill, “If Lee had not won the Battle of Gettysburg.”

A scruffy copy that took a long time to find.

No. 23.

Lester Dent. “The Man Who Shook the Earth,” [in:] Doc Savage Magazine. Vol. 2, No. 6. New York: Street and Smith, February 1934.

An early issue of the enormously popular and long-running Doc Savage Magazine, with a cover by Walter M. Baumhofer. At its peak, Doc Savage Magazine sold 200,000 copies monthly, double the circulation of the science fiction pulps.

Allen Steele writes: “The underpinnings of the Doc Savage adventures may not always make sense, all the same they’re firmly rooted in rational scientific thought. In a sense, these stories are object lessons in Clarke’s Third Law — ‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’ — delivered decades before Sir Arthur put it down on paper.”

No. 24.

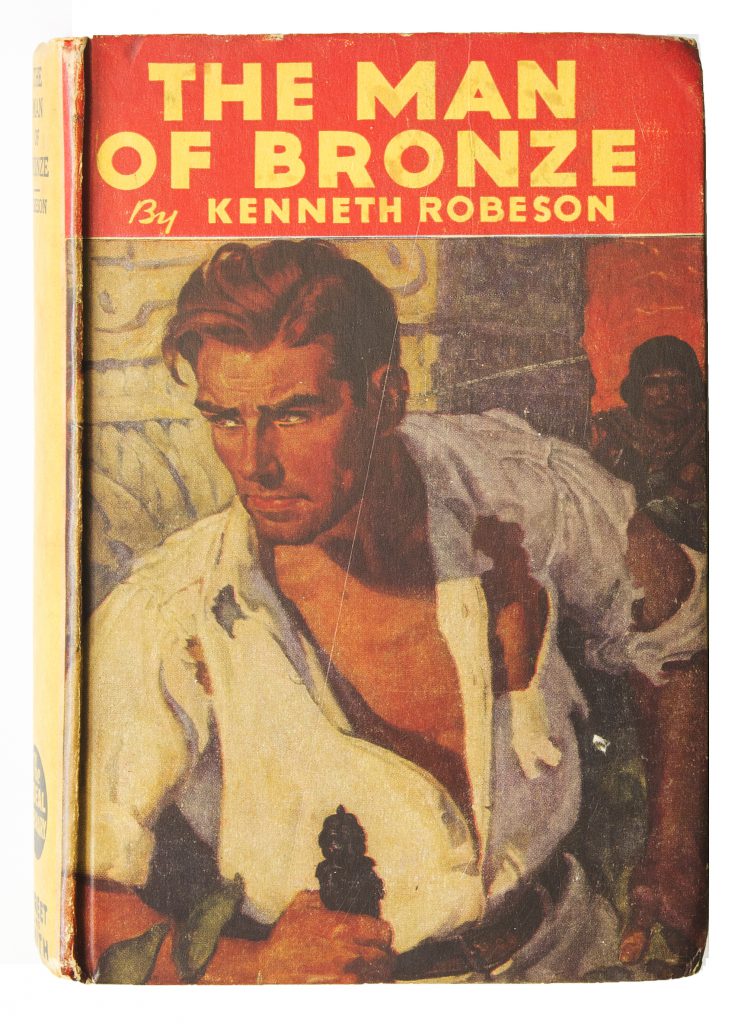

Lester Dent. The Man of Bronze. Doc Savage and His Pals in a Novel of Unusual Adventure. By Kenneth Robeson. New York: Street and Smith Publications, 1933.

Introducing Clark Savage, Jr., polymath, physician, scientist, and brilliant inventor whose physical strength and endurance equalled his intellectual achievements. A superhero before the fact, Doc Savage used his secret wealth to fight arch criminals, oppose corrupt industrialists and politicians, halt the spread of deadly diseases, discover lost races, and travel to the empty places on the map.

Lester Dent (1904–59) wrote more than 130 of the Doc Savage adventures in brisk, headlong prose. First publication in book form.

No. 24.

Lester Dent. The Man of Bronze. Doc Savage and His Pals in a Novel of Unusual Adventure. By Kenneth Robeson. New York: Street and Smith Publications, 1933.

Title page of the first book edition.

No. 24.

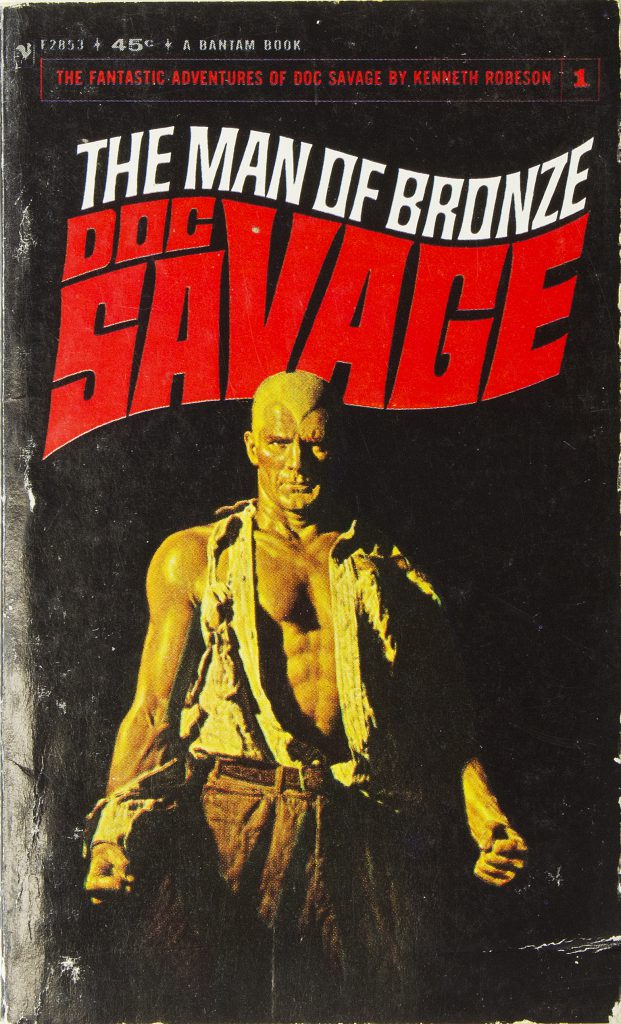

Lester Dent. The Man of Bronze. A Doc Savage Adventure. New York: Bantam Books, October 1964.

The first Bantam paperback reprint of the Doc Savage pulp stories. The cover is by James Bama.

No. 24.

Lester Dent. The Man of Bronze. A Doc Savage Adventure. New York: Bantam Books, October 1964.

One of the books read in childhood that led me to science fiction and the fantastic.

No. 24.

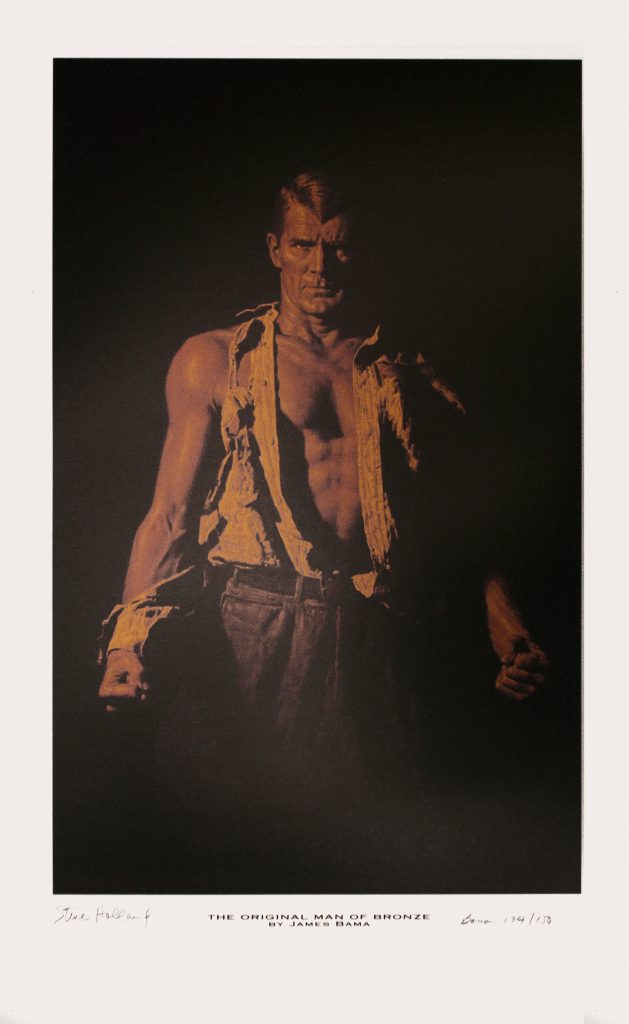

James Bama. The Original Man of Bronze. Anaheim: Graphitti Designs, 1994.

Print of the original painting for the Bantam cover of The Man of Bronze. Edition of 150, signed by the artist and by model Steve Holland.

Prolific and versatile artist James Bama painted more than 60 illustrations for the Bantam covers, and Steve Holland was the model for these and for countless mass-market paperback book covers by Bama and others. Holland was “the embodiment of the spirit of Men’s Adventure circa 1973” (Chris Brown).

No. 24.

William Crawford and D. R. Welch. Science Fiction Bibliography. Vol. 1, No. 1. [All published]. Austin, Texas: The Science Fiction Syndicate, 509 West 26th Street, 1935.

“This brief pamphlet is neither complete nor entirely accurate . . .”

The first bibliography of science fiction, chiefly devoted to chapbooks and fanzines in the first decade after the rise of American pulp science fiction.

No. 25.

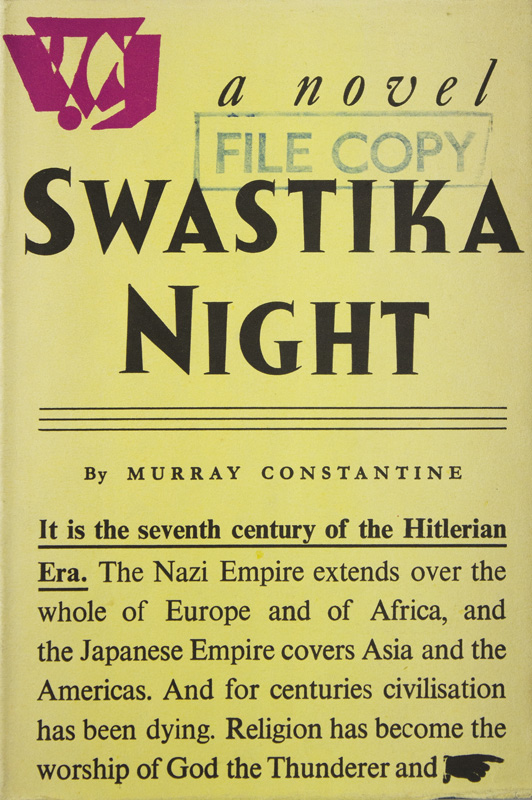

Katharine Burdekin. Swastika Night by Murray Constantine. London: Gollancz, 1937.

Swastika Night is a landmark feminist science fiction novel, set seven hundred years after a Nazi conquest of Europe, where Hitler is worshipped as an Aryan god, all written evidence of the past has been eradicated, and the Jews have been exterminated. Women are kept only as breeding animals, and are deemed to be without souls or intellectual capacity. Some science fiction authors wrote with clarity and prescience about the state of the world in the late 1930s.

The novel was published under a pseudonym, and only in the 1980s did scholar Daphne Patai identify the author as Katharine Burdekin (1896-1963).

The Gollancz file copy, in the rare dust jacket.

No. 26.

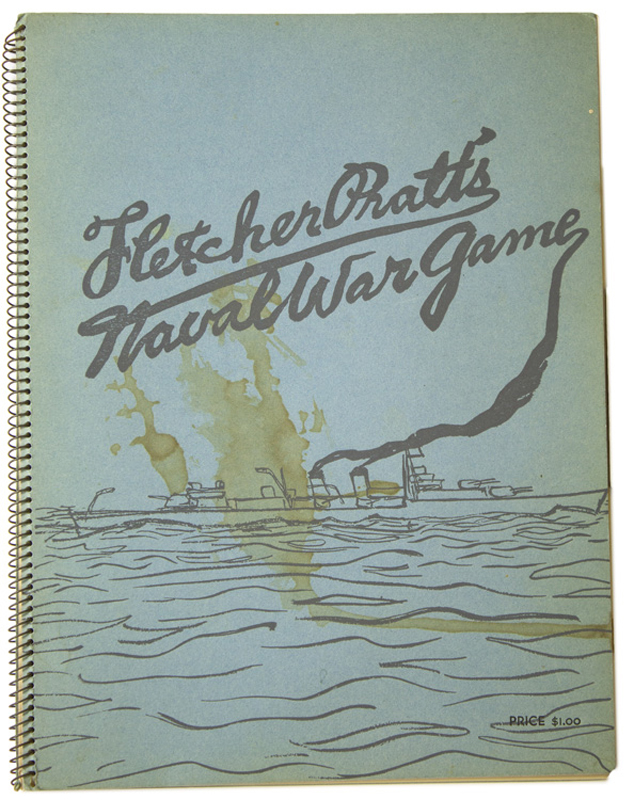

Fletcher Pratt. Fletcher Pratt’s Naval War Game. Drawings by Inga Pratt. New York: Harrison-Hilton Books, 1940.

Fletcher Pratt (1897–1956) was a prolific author on military and naval history, an early contributor to science fiction pulps, and dean of nonfiction at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont. From 1929 onwards, he and his wife Inga organized a naval war game in his New York apartment. This is the published form of the rule book.

With the bookplate of John D. Clark, close friend of the author.

No. 27.

Fletcher Pratt. Fletcher Pratt’s Naval War Game. Drawings by Inga Pratt. New York: Harrison-Hilton Books, 1940.

The title page, with a line illustration by the author’s wife.

No. 27.

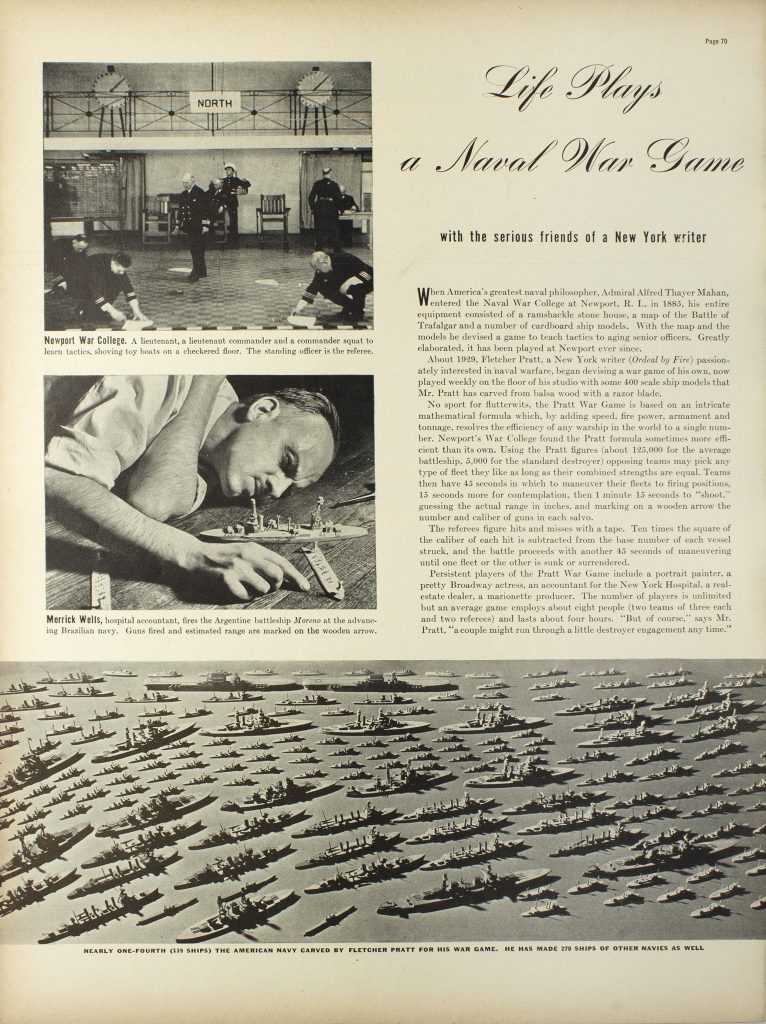

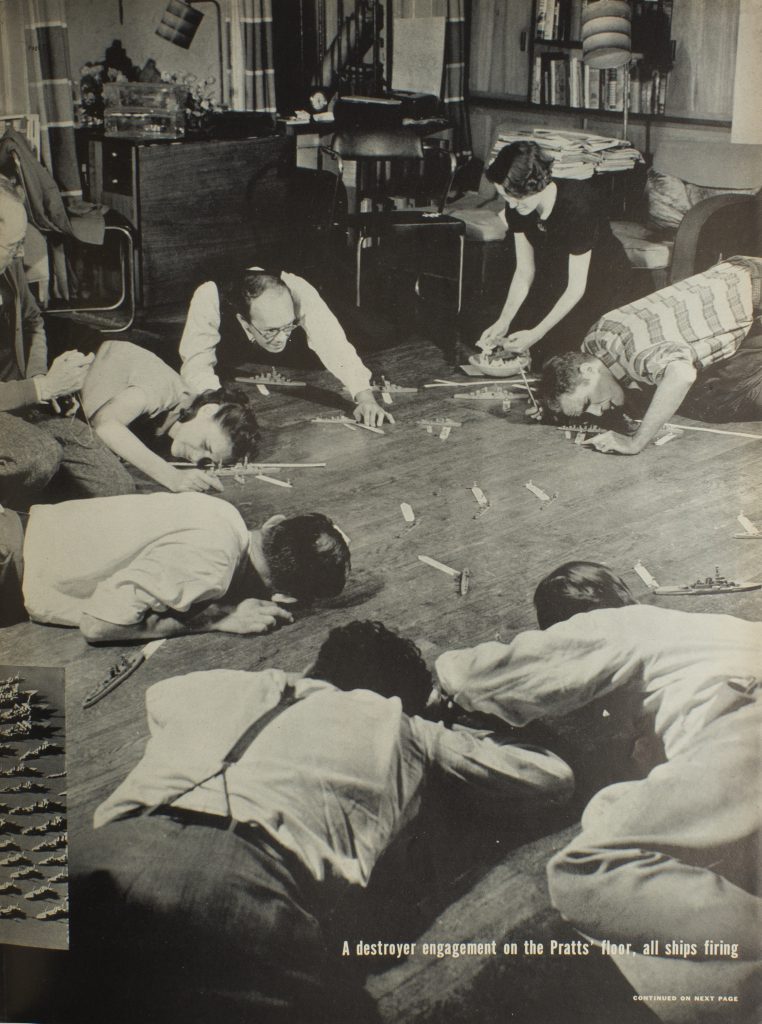

(Fletcher Pratt) “Life Plays the War Game,” [in:] Life Magazine, 10 October 1938. New York: Life Publishing, 1938.

Illustrated photo-essay on Pratt and the circle of war-gamers. Looking at that issue of Life, which reported on the Munich conference with the headline “Hitler Listens to Reason,” I have the sense that the bright people in Fletcher Pratt’s apartment are playing at the edge of an unseen abyss. No doubt we are, too.

No. 27.

(Fletcher Pratt) “Life Plays the War Game,” [in:] Life Magazine, 10 October 1938. New York: Life Publishing, 1938.

Illustrated photo-essay on Pratt and the circle of war-gamers. Looking at that issue of Life, which reported on the Munich conference with the headline “Hitler Listens to Reason,” I have the sense that the bright people in Fletcher Pratt’s apartment are playing at the edge of an unseen abyss. No doubt we are, too.

No. 27.

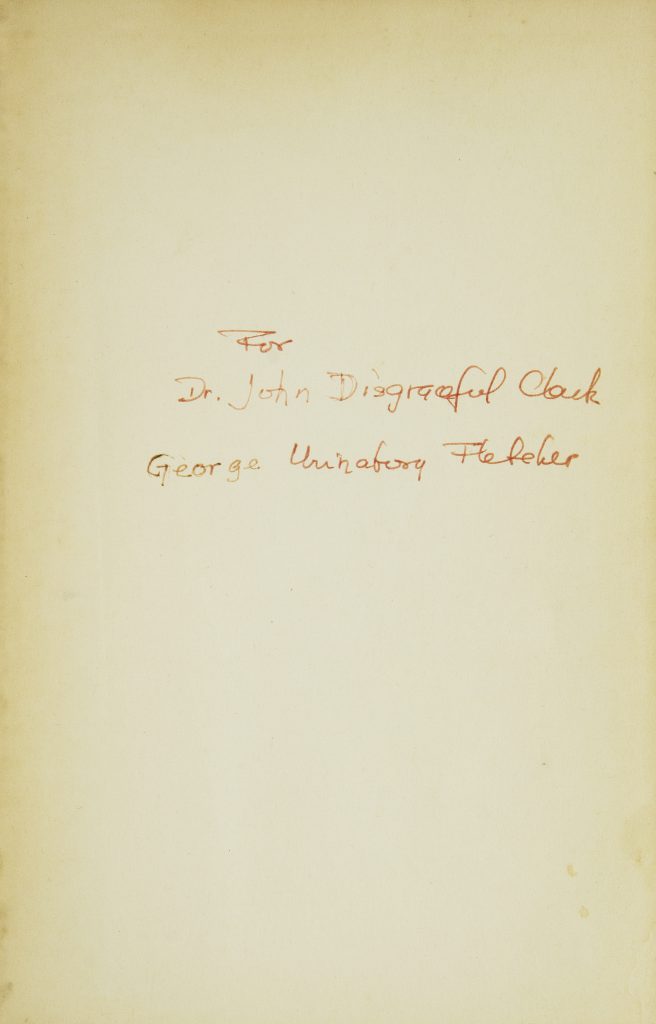

Fletcher Pratt. The Well of the Unicorn. By George U. Fletcher. New York: William Sloane Associates, 1948.

Fletcher Pratt’s The Well of the Unicorn (1948) is a well written and unduly neglected novel of revolution in a late mediaeval fantasy setting. Pratt charts personal and sexual intrigue alongside guerrilla actions, political discussions, and reflects upon the consequences of using magic to achieve revolutionary aims.

Inscribed by Pratt to his friend John D. Clark on the front flyleaf, “To John Disgraceful Clark, George Urinaborg Fletcher.”

No. 27.

Contents

A. Collection Statement

B. Early Works 1762-1912

C. 1920s

D. 1930s

E. 1940s & 1950s

F. 1960s & 1970s

G. 1980s & 1990s

H. Now 2000-2017

I. Bibliography

J. Women Authors

K. Signed or Inscribed